In the early 20th century, New York’s predominantly Issei Japanese community comprised a diverse range of professionals, including businesspeople, diplomats, merchants, industrial workers, business owners, domestic workers, artists, and writers. As the war intensified in the late 1930s, Japanese businesses began to close their New York offices, leading many Japanese-born workers and their families to return to Japan to avoid the escalating hostilities.

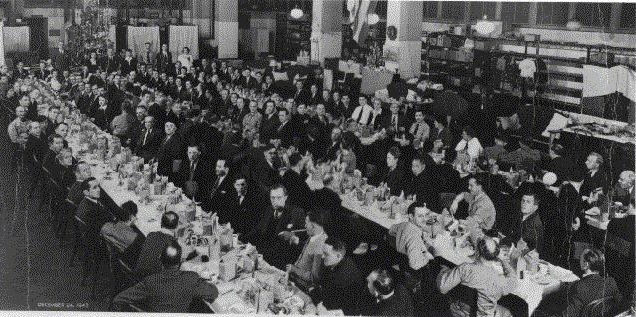

Kichisaburo Nomura was appointed Ambassador to the United States on February 11, 1941. His primary responsibility was to engage in diplomatic negotiations with Cordell Hull, who was the U.S. secretary of state at the time, with the goal of averting war between the two nations. This meeting was the beginning of a series of subsequent meetings, which continued until the attack on Pearl Harbor. After arriving in Washington, D.C., Nomura also engaged in diplomatic efforts in New York, attending a meeting organized by the Japanese Association at the Nippon Club on March 3, 1941, which included discussions with prominent leaders of New York’s Japanese community.

In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066 was issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 12th, 1942, in response to widespread anti-Japanese sentiment and bigotry. This executive order led to the mass removal and internment of over 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans residing in California, Oregon, Washington State, and a portion of Arizona. These individuals were subsequently detained and imprisoned in concentration camps. Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526, and 2527, collectively known as the Enemy Alien Control Program, authorized the federal government to monitor and detain citizens of Japan who were alleged to be dangerous enemy aliens. They were prohibited from possessing items deemed hazardous, including firearms, radios, and cameras, and were confined to designated exclusion zones.

Individuals deemed a potential threat to national security and recommended for internment were held at Ellis Island for an average period of three months before being transferred to various concentration camps, including Fort Meade, Camp Upton, Kooskia, Fort Missoula, and Santa Fe. Notably, many of these individuals were moved between different camps during their internment. At the same time, many faced challenges in securing employment within the city due to pervasive racial discrimination. By 1942, the number of Japanese-born workers in New York had decreased from approximately 3,000 to around 1,500. The great majority of those who stayed were bachelor laborers.

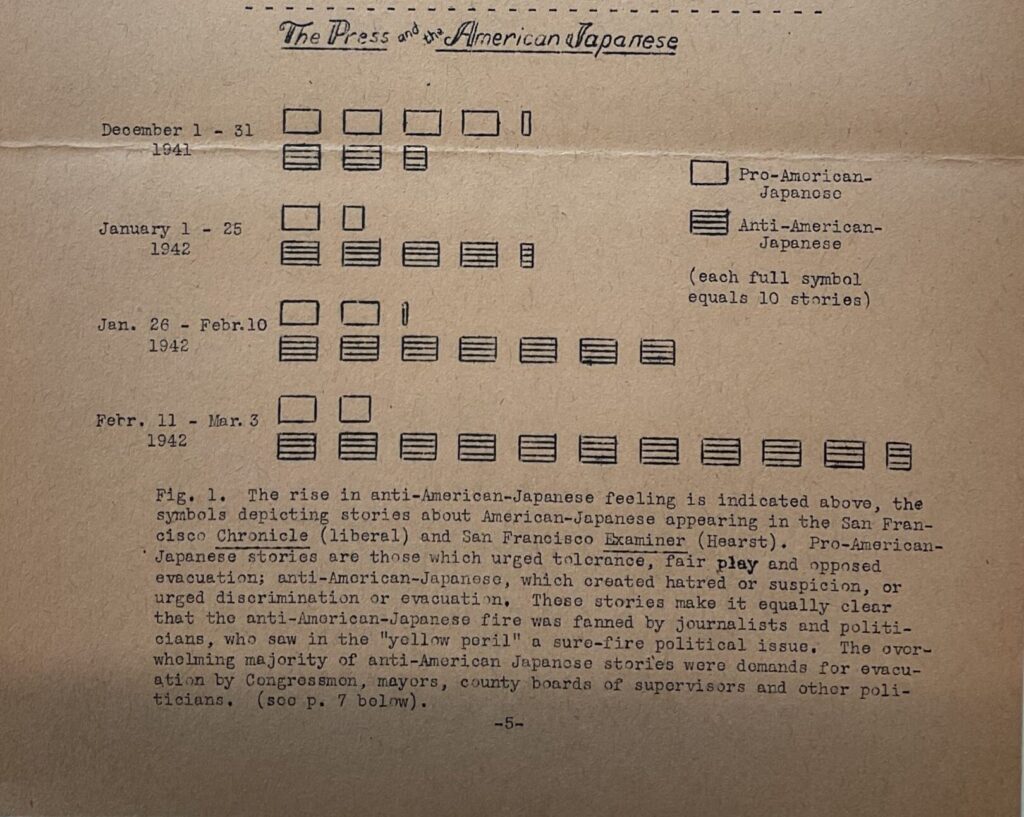

Japanese Internment Report by the American Friends Service Committee, NY Office. Courtesy of AFSC Archive.

Kuro Murase was a distinguished medical practitioner within the Japanese Issei community and a pivotal figure in the welcoming committee for Kichisaburo Nomura at the Nippon Club in New York. Following the Pearl Harbor attack, Kuro Murase was arrested and sent to Ellis Island in July 1942, then interned at Fort Meade, Maryland, Fort Missoula, Montana, and a concentration camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Murase was eventually repatriated to Japan in September 1945.

Dr. Sabro Emy was also a physician who treated many Japanese-speaking patients from working-class and economically disadvantaged backgrounds. After being detained at Ellis Island, he was placed under house arrest and monitored by the FBI until the war ended.

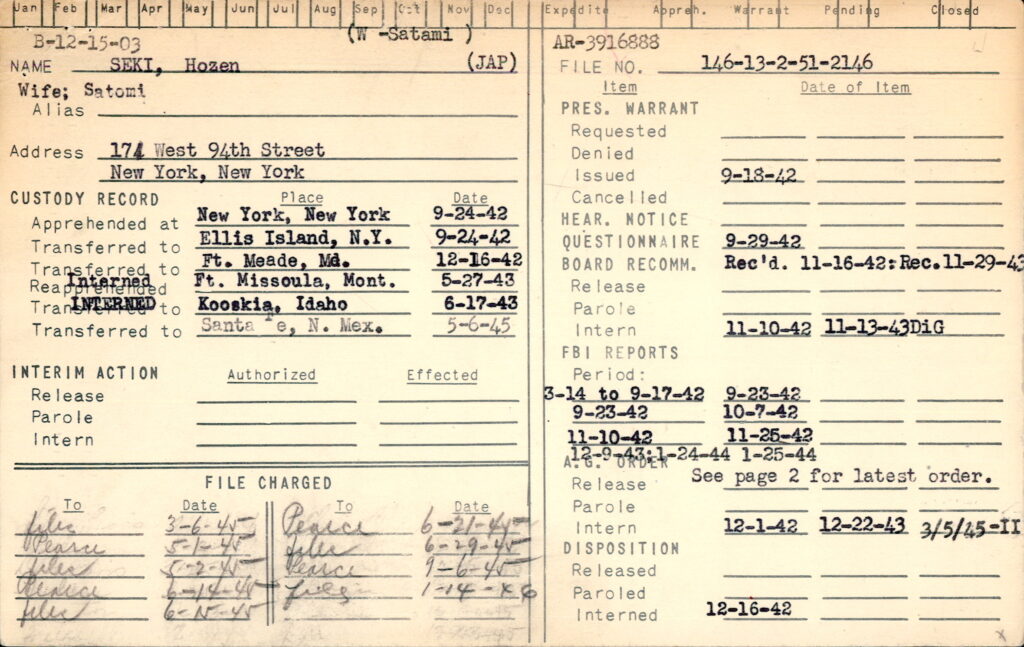

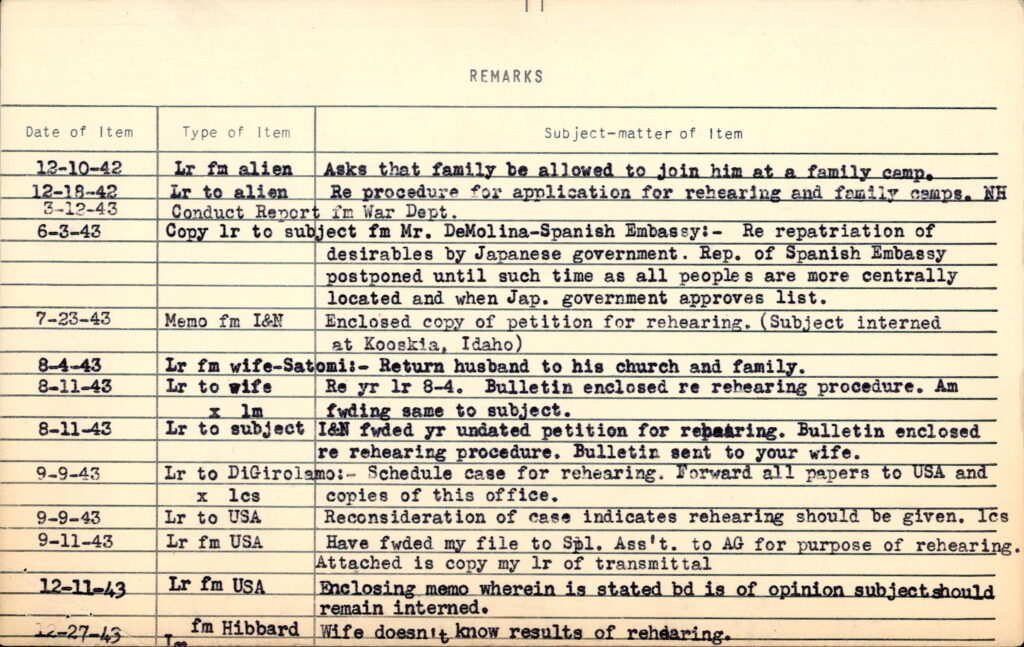

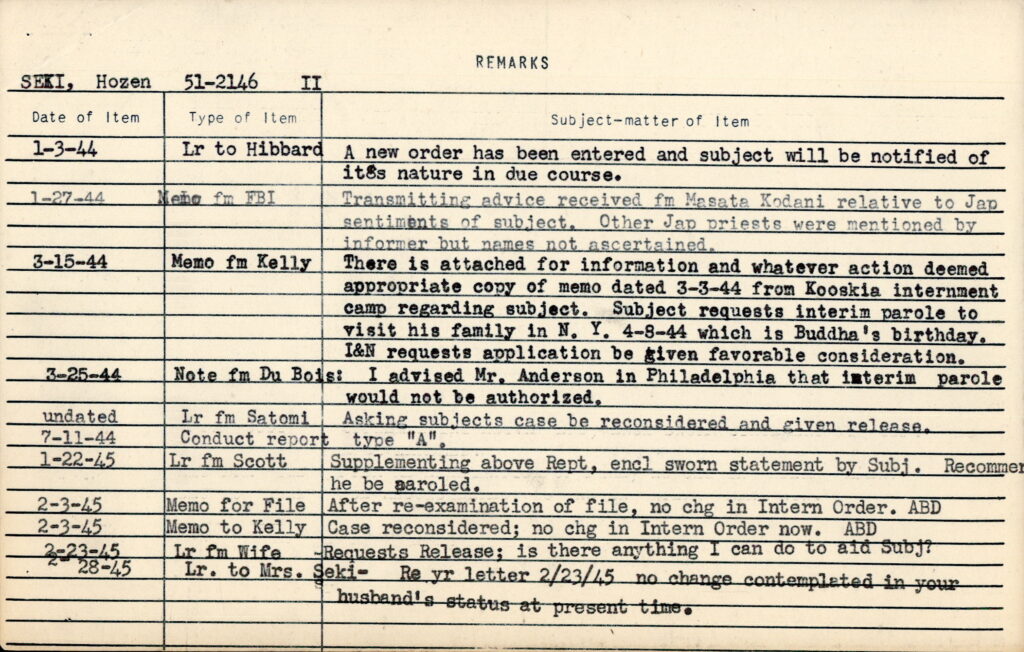

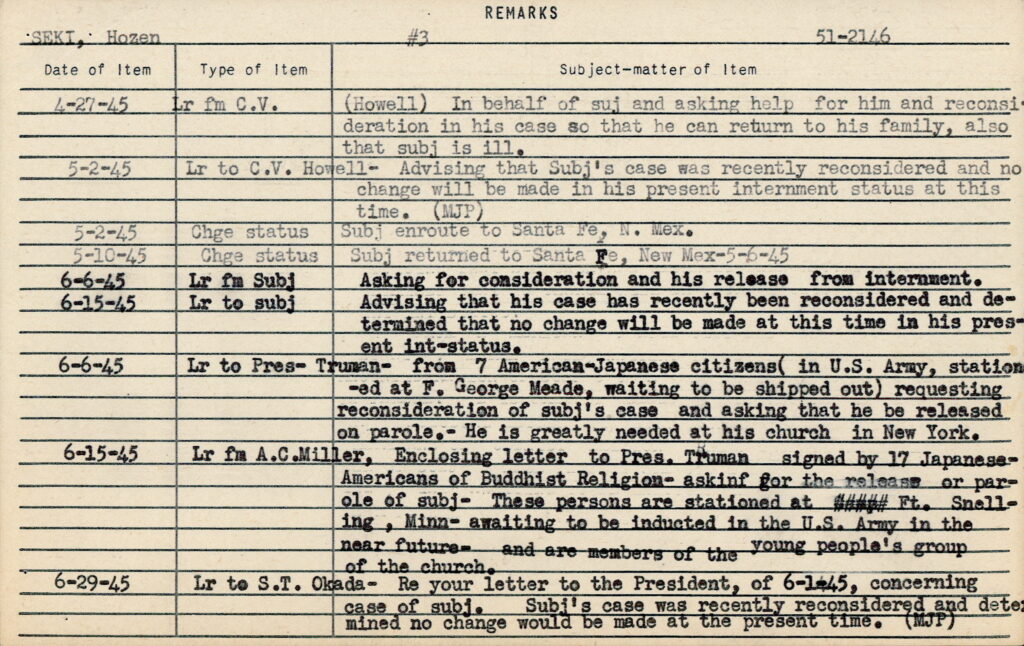

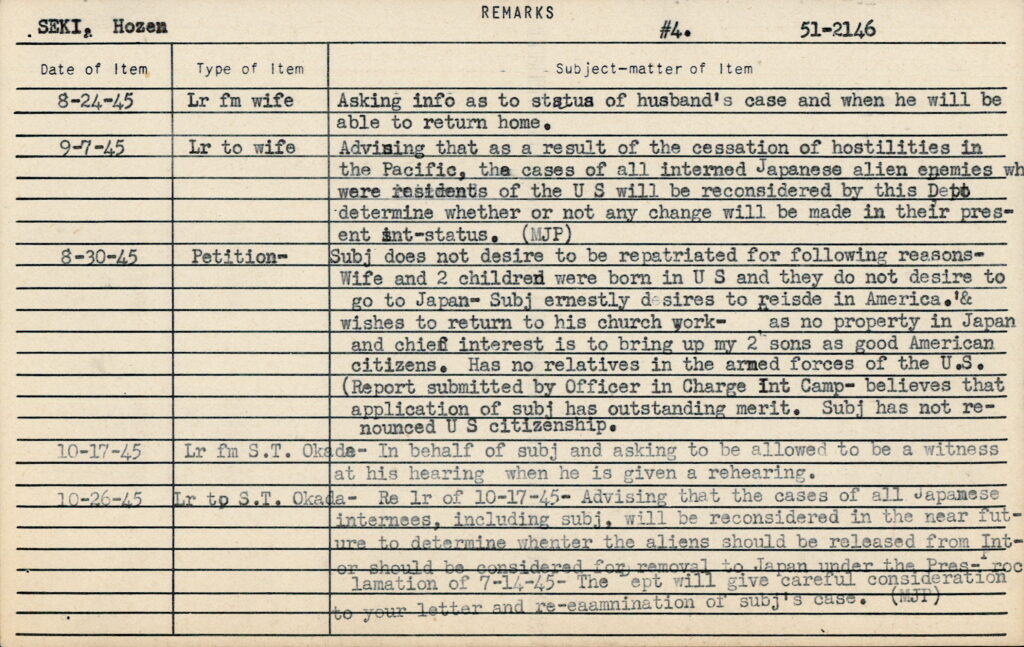

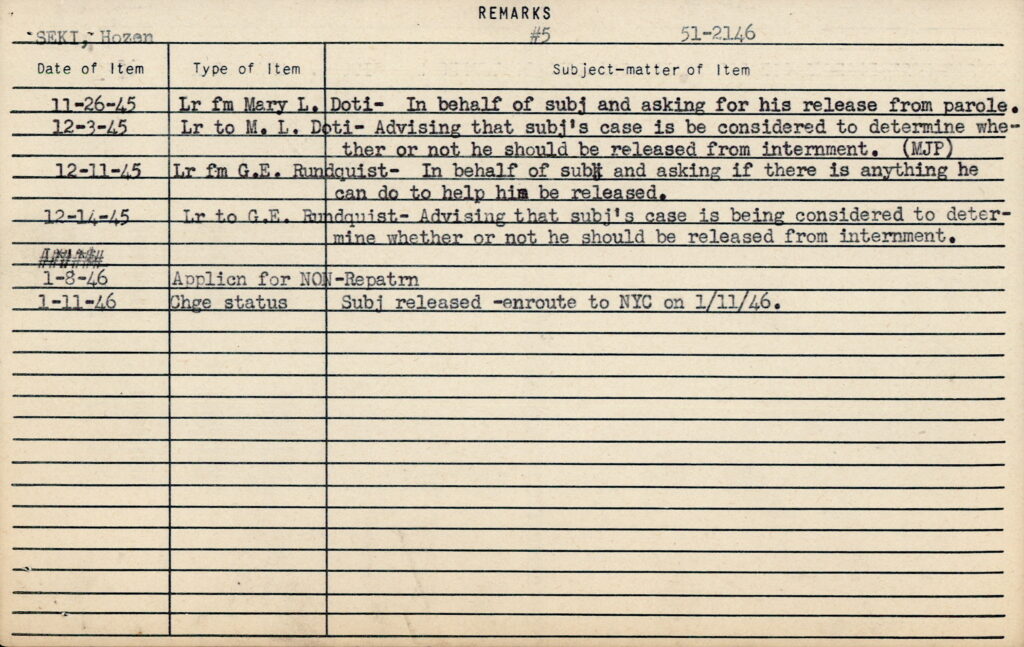

Rev. Hozen Seki, who founded the New York Buddhist Church in 1937, was detained at Ellis Island and sent to camps, including Fort Meade, the hard labor road camp at Kooskia, Idaho, and Santa Fe. His Nisei (the children of Japanese immigrants who were born in the United States) spouse led the church, offering spiritual guidance to the evacuees and serving as a gathering point for Japanese American Buddhist soldiers, including those from the 442nd Infantry Regiment, before their deployment to the European theater.

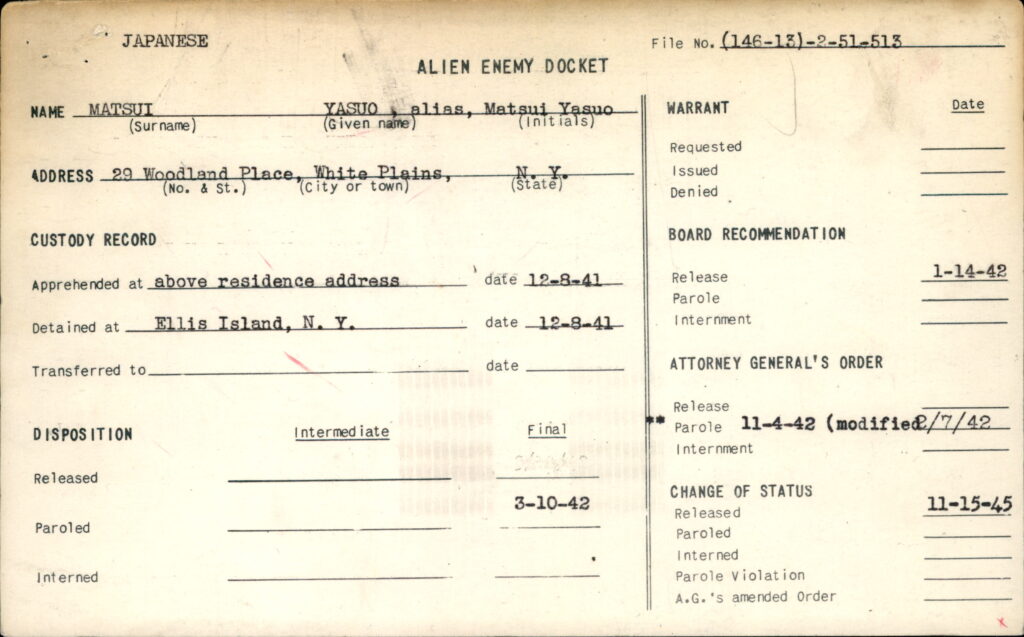

Individuals engaged in artistic and creative professions were similarly detained. Prior to the war, Yasuo Matsui was a prominent architect in New York who had contributed to the design of the Japanese pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair and, more famously, was known for his work on the Empire State Building. However, his professional trajectory took an unexpected turn following his arrest and subsequent two-month detention at Ellis Island. Following his release, Matsui’s professional standing was compromised; he was compelled to report monthly to federal authorities and was subjected to restrictions on his travel until October 1945, a month after the conclusion of World War II.

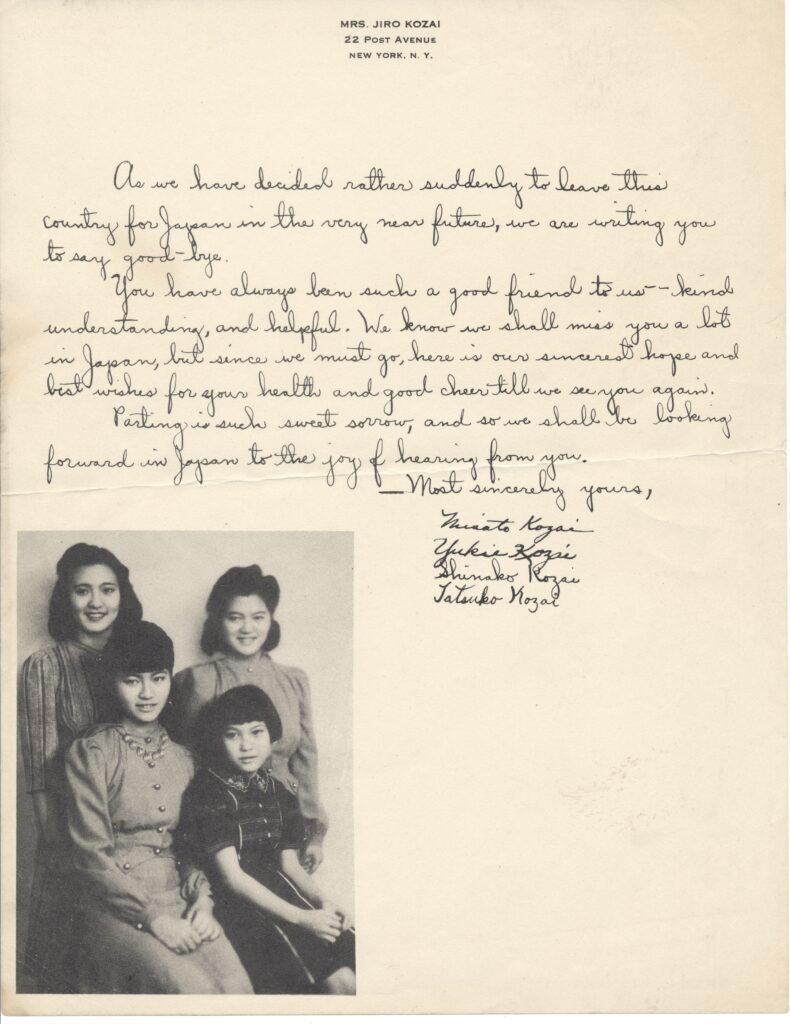

Jiro Kozai was a writer, editor, and owner of the Japanese American, a Japanese-language newspaper in New York, and president of the Japanese Association of New York in the 1920s. Moreover, he played a pivotal role in the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where he spearheaded the mobilization of local volunteers and successfully secured financial resources from the Japanese community in New York. Kozai’s activities during this time led to his arrest and internment at Ellis Island and Camp Upton. This experience forced him to return to Japan with his Nisei wife and daughters.

Takeo Shiota, a renowned Japanese gardener and landscape architect, is particularly noteworthy for his design of the Japanese Hill-and-Pond Garden at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, constructed between 1914 and 1915. During World War II, anti-Japanese sentiment erupted, and widespread discrimination led to the temporary closure of the Hill-and-Pond Garden. Shiota was apprehended and held on Ellis Island, then later passed away in 1943 after being transferred to a South Carolina camp.

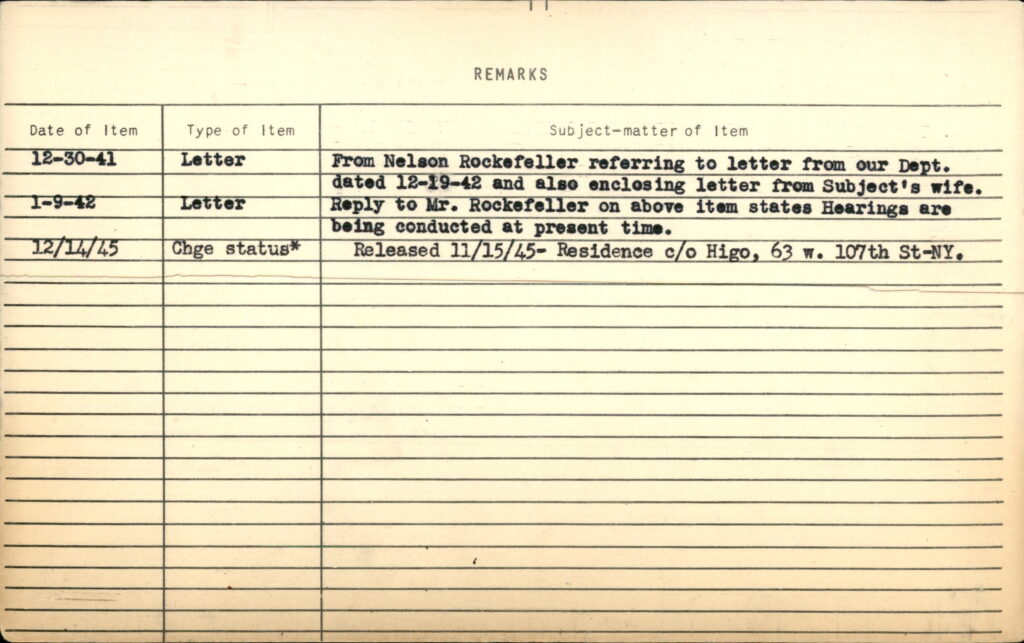

Yosei Amemiya, a New York-based artist and architectural photographer, was similarly detained at Ellis Island. In 1941, Nelson Rockefeller, a prominent collector of Japanese art, wrote a letter requesting his release. However, Amemiya was interned for nearly four years until he was finally released in 1945.

The wives and children of Japanese New Yorkers detained on Ellis Island encountered considerable hardship. A portion of these families possessed sufficient savings to sustain themselves during the period of their husbands and fathers’ detention. These men were often the sole wage earners for their families. However, for others, the situation was dire, leading to destitution. The Federal Council of Churches of Christ in America endeavored to provide assistance to Japanese individuals impacted by wartime confinement, offering food and housing for families that had been left behind when their male family members were taken to Ellis Island.