エリス島での不正義は、民主主義そのものへの問いを引き起こす。日系アメリカ人は、収容下にあっても、忠誠、市民権、権利をめぐって激しい議論を交わした。特に二世たちは、民主主義は約束されるものではなく、自ら手にするものだと証明しようとした。彼らの行動と犠牲は、アメリカ社会の矛盾を突きつけ、より真の民主主義実現に向けて国を押し動かした。

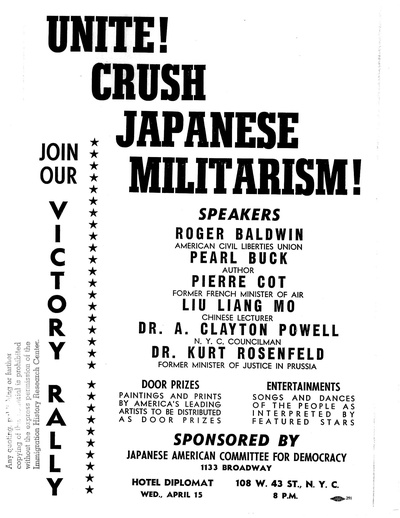

戦前、ニューヨークの日本人コミュニティは親東京派とプログレッシブ派に分かれていた。プログレッシブ派は、戦争の脅威が迫る中、差別による解雇から日系コミュニティを守るために結束し、「アメリカ東部在留邦人民主化委員会」を結成した。この連合は、芸術家や活動家、ジャーナリストで構成されていた。1940年8月、 ラリー・タジリやトーマス・コムロら一世と二世の連合が、「合衆国東部における日本人居住者の民主的処遇のための委員会」を設立した。この組織は、在米日本人社会がアジアにおける日本の侵略に責任がなく、アメリカ国民や政府に対して悪意を持っていないことを、アメリカ国民に納得させるための必死の取り組みに基づいて結成された。この組織の初代会長は、ニューヨーク日本人メソジスト教会の若き日本生まれの牧師、アルフレッド・アカマツ師であった。委員会の主な焦点は日系社会における社会奉仕活動で、日系企業の閉鎖によって影響を受けた人々の失業保険取得を支援し、教会や政府からの雇用支援についての手配をした。委員会は、ニューヨークの日系社会の社会調査を行い、最も緊急なサービスの必要性を確認し、ニューヨークの日系人に対する差別に抗議した。

太平洋戦争終結後、「The Christian advocate」に掲載されたニューヨーク日本人メソジスト教会牧師アルフレッド赤松師へのインタビュー。カリフォルニア州立大学フラートン校、大学アーカイブ・特別コレクション

真珠湾攻撃とアメリカの参戦の余波で、状況は大きく変化した。在ニューヨーク日本領事館 は閉鎖され、米国東部在留邦人民主待遇委員会は解散させられ、司法省は、不忠誠の可能性があるとして、エリス島で多数の実業家や地域社会の指導者の拘束を開始した。これらの逮捕は、赤松牧師をはじめとする米国への不忠誠の証拠がない日本人にも及んだ。エリス島での日本人ニューヨーカーの大量拘留は、被拘禁者自身、その家族、そしてより広いニューヨークのコミュニティに影響を及ぼした。被拘禁者の中には、日本への帰国を望む者もいれば、アメリカ人であるにもかかわらず、蔓延する反日人種差別のために疎外感を味わった者もいた。

多くの人が、自分のアイデンティティや 自分の帰属意識に関する複雑な感情や 心境と格闘し、内なる葛藤の中にいた。ニューヨーク市の福祉当局は、日本人や日系アメリカ人に対する配慮に欠けていた。民間の団体では、クエーカー教徒の団体、アジア救援公認団体(AFSC)、教会日系人委員会などが、キリスト教会に、生活を破壊された人々に雇用と住居を提供する支援を訴えた。

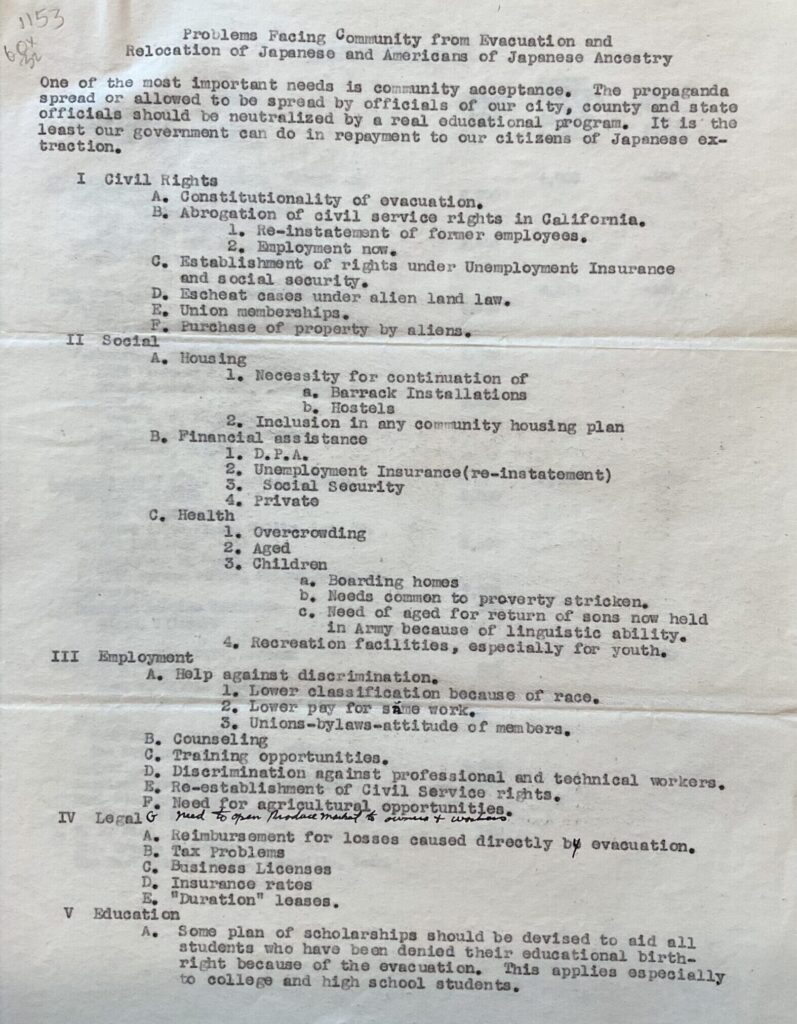

こうした動きに呼応して、150人が参加する市民集会が開催され、 日系人民主化委員会(JACD)が設立された。JACDは、トーマス・コムロを会長に選出し、6つの小委員会を設置し、定期的なニュースレターの発行を開始した。ニュースレターには、パール・S・バック、アルバート・アインシュタイン、フランツ・ボースといった著名人を含む、進歩的で民主主義を支持する諮問委員会が設けられた。1942年3月中旬、JACDは、職業差別に直面している日系アメリカ人に雇用機会を提供する連邦機関の設立を提唱した。JACDは、第二次世界大戦におけるアメリカの戦争支援を目的とした集会を組織し、強制収容所からニューヨークへ移転する日系アメリカ人を支援し、一世と二世が集い交流する場を提供した。JACDニュースレターは毎月発行され、ニューヨークの日系コミュニティーに関する情報を発信した。

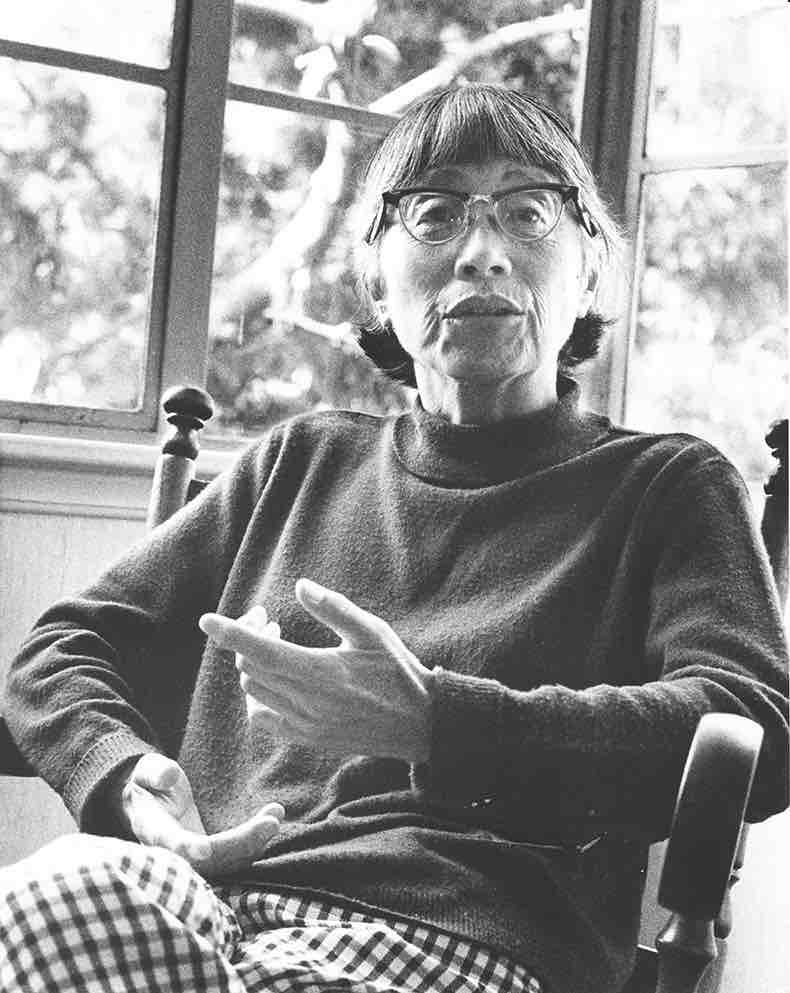

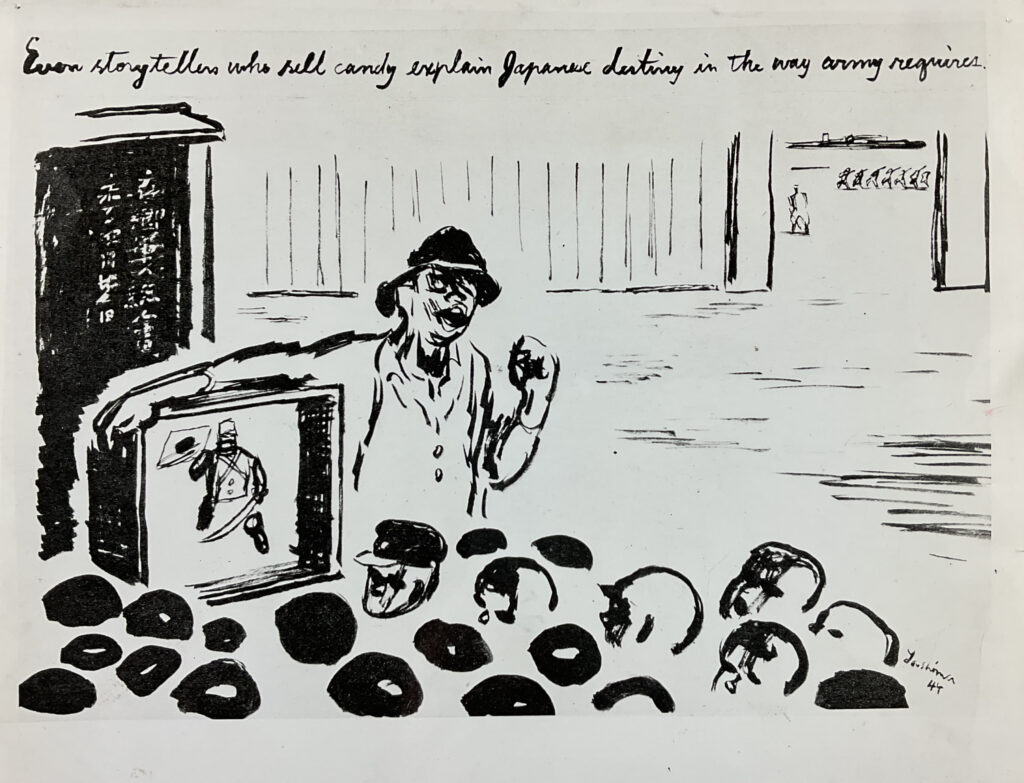

1943年初め、ノリ・イケダ・ラファティ はニューヨークに移り、JACD初の有給スタッフとして採用された。これをきっかけに、ラファティに続いて、二世の活動家仲間がニューヨークに集まるようになり 、JACDは、徐々に二世を中心としたメンバーで構成されるようになった。1944年には、一世の理事が辞任し、二世のメンバーがJACDのリーダーに選出された。また、芸術家の国吉康雄とイサム・ノグチの援助により、JACD芸術評議会が設立されました。協議会の主な目的は、民主主義を支持し、当時の日本の軍国主義に反対するためのプロパガンダ・ポスターを制作することだった。ニューヨークを拠点とする作家やジャーナリストもこの活動に参加した。

日系アメリカ人民主化委員会ニュース・レター、第2巻第2号、1943年11月。オクシデンタル大学図書館特別コレクション提供

レオ・アミノは、イサム・ノグチとともに1939年のニューヨーク万博に出展したアーティストの一人である。真珠湾攻撃後、アミノのニューヨークの自宅は捜索され、シークレットサービスの尋問を受けた。戦争中、アミノは日本政府の法律文書を翻訳した。アミノはまた、ノグチと国吉が議長を務めたJACD芸術評議会の執行委員でもあった。

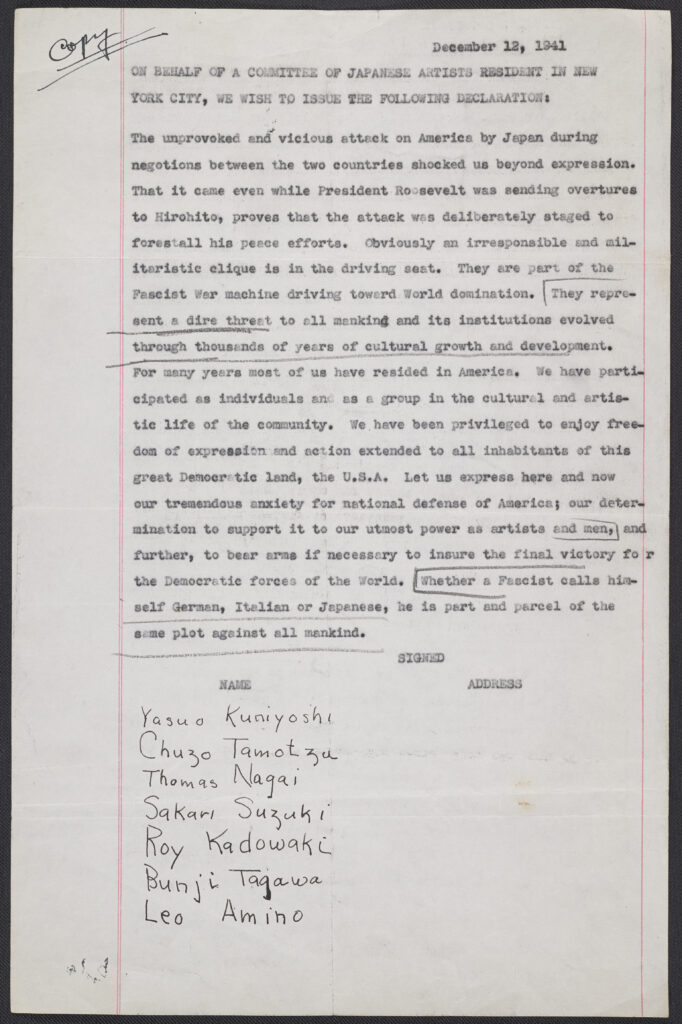

1941年12月、アミノ、国吉、保、ノグチ、 永井トーマス、門脇ロイ、鈴木盛,、田川文治 が日本ファシズムに対する抗議文書に署名。矢島太郎 は1939年に日本を出国し、アメリカ陸軍に入隊、アメリカ戦争情報局(OWI)と戦略サービス局(OSS)の芸術家として活躍した。1943年、戦前の日本を描いた310ページの自伝的絵本『新しい太陽』を大人向けに出版した。

1944年2月11日、「民主主義のための日系アメリカ人芸術評議会」会長、国吉康雄の声明。スミソニアン協会公文書館提供。

石垣綾子は一世のジャーナリスト、活動家、フェミニストであり、1940年に田川(源五)君の協力を得て回想録『レストレス・ウェーブ』を出版した。戦時中の日本社会と軍国主義に対する強い批判は、日本政府から否定的な注目を浴びることにもなったが、アメリカでは高く評価された。綾子と彼女の伴侶である画家の石垣栄太郎は、敵性外国人として登録しなければならなかったが、その民主主義支持の立場から投獄されることはなかった。しかし、夜間外出禁止令、抜き打ち検査、職を失うなどの処分を受けた。そして1942年、綾子はOWIで働くようになった。

1943年から1944年にかけて、田川(源五)君 は、ガール・リザーブズ(1918年に始まったYWCA(Young Women's Christian Association)のプログラム)のための雑誌『本棚』に、一連の物語を掲載した。この物語集で、君は架空の会話を交えながら、アメリカと日本の文化、移民、社会への融合について読者に説いた。君の配偶者である 田川文治 もJACDで活躍し、君の著書『天皇の死を悼む人へ』に挿絵を寄せた。