ARCHIVE of Artwork and Reviews

Ch. 1, Fig. 1

Kotato Gado, Fairly Clouds, c. 1917

“Cloud” was probably exhibited at the New York Japanese Art Association’s 1917 exhibition. The rightside of the painting depicts an oni (demon)-like figure, while the left shows a nymph with a frightened expression, as if fleeing from an oni.

Fumi no Mori Motegi

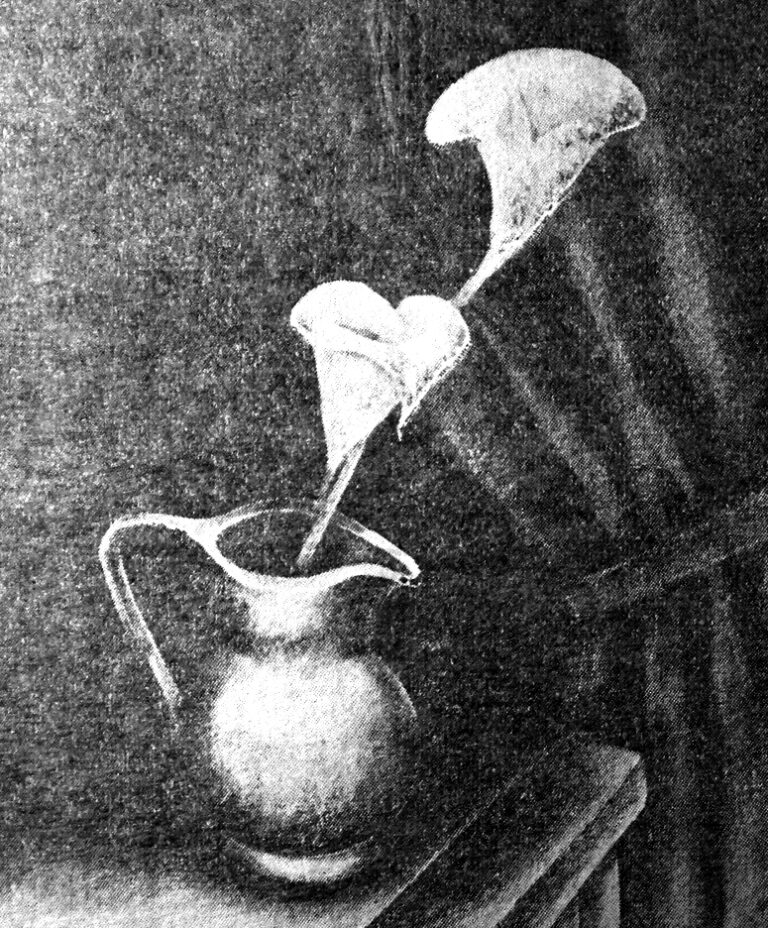

Ch. 1, Fig. 2

Yukihiko Shimotori, Tea Pot, c.1916

“Tea Kettle” depicts a table covered with a floral tablecloth, a brown teapot in the center, and a green tea set in the background.

Catalogue of the Yukihiko Shimotori exhibition, 1983

Ch. 1, Fig. 3

Kotato Gado, Take Gari, c.1917

Four women are depicted in a forest, dressed in kimonos, with Japanese hair and hairpins. The woman on the far left is holding a kiseru (a Japanese smoking pipe). The woman next to her is holding a chestnut. The woman crouched on the right seems to have found a mushroom. The autumn leaves on the trees and the scarlet red on the hem of the women’s kimonos add an Eastern European flair to the scene. This Western-style painting is based on a Japanese motif.

Fumi no Mori Motegi

Ch. 1, Fig. 4

Seisho Hamachi, Fifth Avenue, c.1918

The American flags are waving from the window of a building, and the Flatiron Building on Broadway at 23rd Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City can be seen at the back of the image. This painting of Fifth Avenue in New York City is similar in composition to Childe Hassam’s “July Fourteenth, Rue Daunou.”

Private Collection

Ch. 2, Fig. 5

Commemorative Photo at the Exhibition of the Gacho Kai, 1922

In the center of the front row is Furudo Masado, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi is on the right side of the front row, facing sideways. Eitaro Ishigaki is on the far left in the back row, Kyohei Inukai is second from the left in the second row, and Toshi Shimizu is fourth from the left in the back row.

Ch. 2, Fig. 6

Photo of Eitaro Ishigaki (Evening Telegram New York 1922 Nov. 4)

Eitaro Ishigaki in his studio. Photo of “Young Japanese Artists Finds Strange Contrasts in American Men and Women”(Evening Telegram, Nov. 4, 1922)

Image Source:

Ch. 2, Fig. 7

Kotato Gado, Family, c.1922

This painting depicts a family of five gathered around a table with a brown room in the background. The hexagonal wall, the electric light in the center of the room, and the family around the table may pray before the meal. The painting evokes a sense of warmth and tenderness.

Image Source:

Ch. 2, Fig. 8

Kotato Gado, Traffic, c.1920

Standing in the background are the buildings of New York City, and the black horizontal line running slightly above center is probably an elevated railroad. In the foreground, countless geometric lines depict a line of carriages running down a boulevard and people passing by on the street. One can almost hear the hustle and bustle of the city.

Image Source:

Ch. 2, Fig. 9

Kotato Gado, Rush Hour in Subway, c. 1918

This geometric line drawing depicts the interior of a crowded subway car during rush hour. This work was also exhibited at the 3rd Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1919. In “The Japanese,” […]the artist skillfully captures the movement of the “rush hour” vibe as a scene from the present-day scene. The “Family,” which seems to be a recent work, appears to be more and more mature and settled. (Souji, “Review of the Painting Exhibition,” Nihonjin (Japanese), No. 97, October 25, 1922).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1919

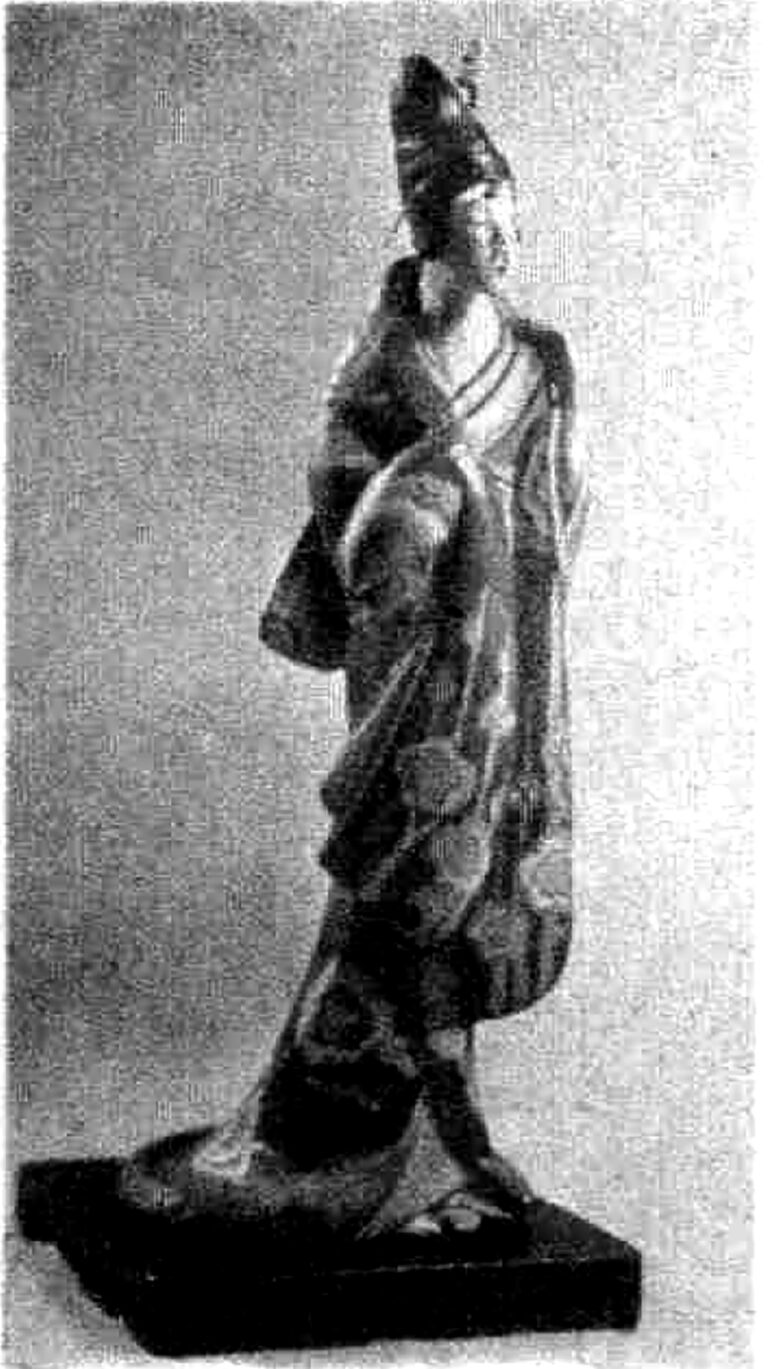

Ch. 2, Fig. 10

Masaji Hiramoto, Rodin, c.1922

Sculptor Shoji Hiramoto exhibited “Rodin,” “Buddha,” and “Joffre.”

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1922

Ch. 3, Fig. 11

Photo of the Salons of America, c.1922-1923

The Society of Independent Artists was established in 1917 and the Salons of America was established in 1922. These organizations held an annual no-jury, non-prize exhibition that was open to anyone, regardless of nationality or technique, and many Japanese exhibited their works.

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 12

Shinyo Hagida, The Red Bath, c. 1918 (1918 Exhibition of the Japan Association of Independent Artists)

The Red Bath by Shinyo Hagida, exhibited at the 2nd Exhibition of the Japan Association of Independent Artists in 1918, depicts a Japanese public bath with curves as the basic tone. The title of the work surprised people in the region who were unfamiliar with public baths.

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1918

Ch. 3, Fig. 13

Kotato Gado, Rush Hour in Subway, c. 1918

The New York Shimpo (New York, 1919) praised this work, which depicts the interior of a crowded subway car with geometric lines, as “expressing a Futurist mood without regret, with a pleasing brushstroke and orderly harmony. (Ishigaki Crucible, “Independence”). (Ishigaki Rutsubo, “Independent Art Association’s Japanese Painter,” The New York Shimpo, April 2, 1919).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1919

Ch. 3, Fig. 14

Kotato Gado, An Accident (Accident/Injury), c. 1919

On a street beneath an elevated railroad, two figures wearing a brown and a black coats appear to be policemen. At their feet, we see a figure lying on the ground. They are surrounded by many people, perhaps at the scene of a traffic accident, indicating the tense situation at the scene ofthe incident.

Fumi no Mori Motegi

Ch. 3. Fig. 15

Kotato Gado, The Traffic, c. 1920 (Independent ArtistsExhibition, 1921)

Against a backdrop of buildings in downtown New York City, an elevated black railroad track running horizontally. The work is filled with countless geometric lines that bring to life the line of carriages running down the street and the people passing by on the road, as if one can almost hear the hustle and bustle of the city. The work of Mr. Gado is alwaysinteresting for its unique conception, technique, and colorpalette. (“Impressions of Japanese Artists at the Exhibition of theIndependent Art Association,” The Nichibei Jiho, March 5,1921)

Image Source:

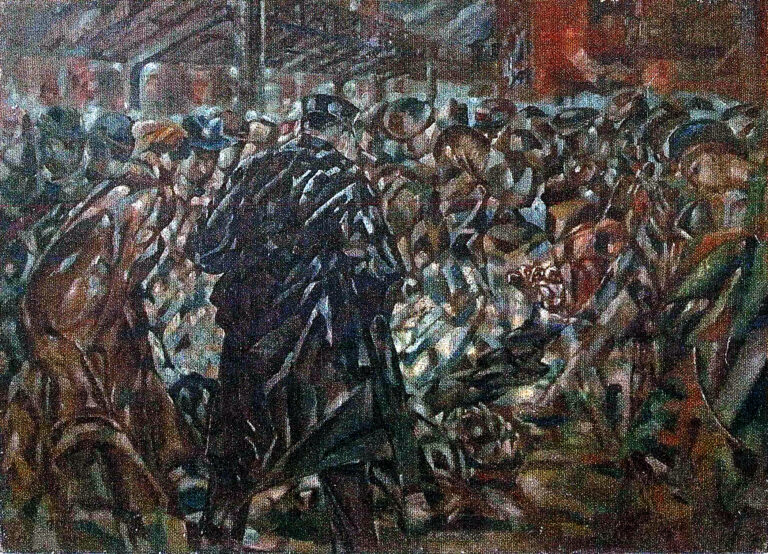

Ch. 3, Fig. 17

Kotato Gado, The Ball, c. 1922 (1922 Exhibition of theAssociation of Independent Artists)

The work is full of the dynamism of a ball, depicting a large number of men and women dancing in pairs with geometric curves and vivid colors.

Fumi no Mori Motegi

Ch. 3, Fig. 20

Kotato Gado, An Infant, c. 1922 (Salons of America,1922)

In a forest with a view of the mountains in the distance, a woman sitting on a bench in the shade of a tree holds an infant in her arms, a figure poses next to her with the infant and a dog lounges peacefully at their feet. The green trees reminds us of the warm season. A cow-like animal can be seen to the left of the woman holding the infant. This work seems to capture a scene in the late afternoon.

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 21

Kotato Gado, Block Party, c.1922 (Independent Artists Exhibition, 1923)

A large number of people wearing hats are seen dancing in a valley between buildings in New York City. The curved lines depicting the woman in the red dress in the center and the figures dancing around her seem to convey the rhythmic music and even the excitement of the party.

Fumi no Mori Motegi

Ch. 3, Fig. 24

Kotato Gado, Ambulance, c. 1920 (Salons of America,1923)

This work depicts a person being carried out of a room in a downtown tenement on a stretcher while onlookers surround it. The figures in the center of the painting are brightly colored and appear to be being quickly carried out of the building.

Fumi no Mori Motegi

Ch. 3, Fig. 25

Kotato Gado, Subway (Communication in the Under Surface), c.1923(1924 Exhibition of the Association of Independent Artists)

“Communication in the Under Surface” depicts a view of a subway stairway during rush hour, as if looking down from above. The many figures descending from the newly arrived subway are depicted in curving lines, dynamically expressing the crowded station.

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 16

Toshi Shimizu, Yokohama Night (Impression of Yokohama, Night View of Yokohama), 1921

Two similar works with the same title and very similarcomposition have been identified. This work is one of themand is said to have been in the collection of George Bellows.The Nichibei Jiho (The Japan-America Times) wrote, “Theidea is colorfully and dramatically executed. It depicts theactivities of an old woman in the floating world, includingstores, liquor stores, geisha parlors, courtesans, students,Westerners, and navy blue-collar workers in a corner ofdowntown Yokohama, and is poetic and dramatic in bothconception and technique and composition. (Impressions ofJapanese Artists at the Independent Art AssociationExhibition, The Japan-America Jiho, March 5, 1921).

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 18

Toshi Shimizu, Ice Cream Pavilion (House at Dyckman), c. 1922 (1922 Independent Artists Exhibition)

This work depicts the area near Inwood in northernManhattan, where Toshi Shimizu lived at the time. Against abackground of rows of tenements, a parent and childshopping at an ice cream store, a figure walking his dog onthe left, and construction workers at a building site reflect thedaily life of a residential neighborhood.

Image Source:

Ch. 3. Fig. 19

Toshi Shimizu, In a Chop Suey Palor (In the Chop Suey), c. 1921 (Independent Artist Exhibition, 1922)

In the Chop Suey restaurant at dusk, a woman is seentalking to a sailor in the center with her hands around hiswaist. Chinese-style lamps are on the ceiling, and a waiterbusily serves food in a crowded restaurant. It feels as if weare in the midst of a conversation, and we can hear thesounds of the people talking and the dishes being served.

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 22

Toshi Shimizu, China Town at Night, New York (China Town), 1922 (1923 Independent Artists Exhibition)

Tourists riding a bus through Chinatown at night. Thepainting depicts people enjoying a meal on the second floorof the red-roofed restaurant on the left, and even a drunkenman lying on the street. The Nichibei Jiho (Japan-America Times) wrote, “Shimizu’swork, as usual, is an interesting depiction of the activities ofthe floating world with a deep emotional appeal. Both“Diekmann’s House” and “China Restaurant” are particularlyinteresting because they are so expressive in their conception, coloring, and technique. (Mumyoji, “Dokuritsu Bijutsu Tenkan – Gado Hiramoto Watanabe – A Short Review of Mr. Shimizu’s Works,” Nichibei Jiho, April 1, 1922). With Asian style buildings and people in the background, thepainting depicts a strange town where Westerners on a cartouring the city are amused by the strange atmosphere.(Kageji Morningside, “Seeing the Independent ArtExhibition,” The Japan-America Jiho, March 17, 1923)The subject matter and atmospheric style of the paintingswere highly praised.

Image Source:

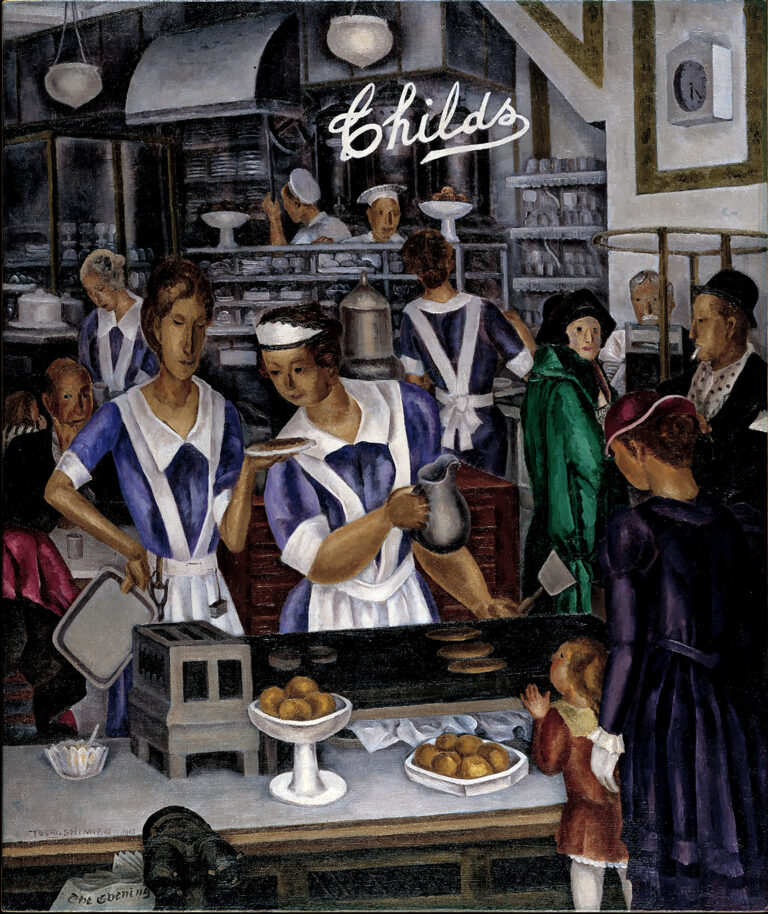

Ch. 3, Fig. 26

Toshi Shimizu, Childs, 1924 (1924 Independent Artists Exhibition)

Two women in blue aprons are cooking pancake-like food inthe center. Behind them are the cooks busily preparing foodin the kitchen and finery-dressed customers.

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 23

Torajiro Watanabe, Symbol of Righteousness, c. 1923 (1923 Independent Artists’ Exhibition)

Torajiro Watanabe, who contributed art reviews toJapanese-language newspapers, was also active as anartist and exhibited this folding screen depicting a dragonascending to the heavens at the 7th Independent ArtistsAssociation Exhibition in 1923. The Nichibei Jiho (Japan-America Times) reported, “The pair of folding screens depicting the Ascension of the Dragon was a particularly striking work in the exhibition hall. (Kageshi Morningside, “Seeing the Independent Art Exhibition,” The Japan-America Jiho, March 17, 1923), and it was talked about as an Eastern-style work.

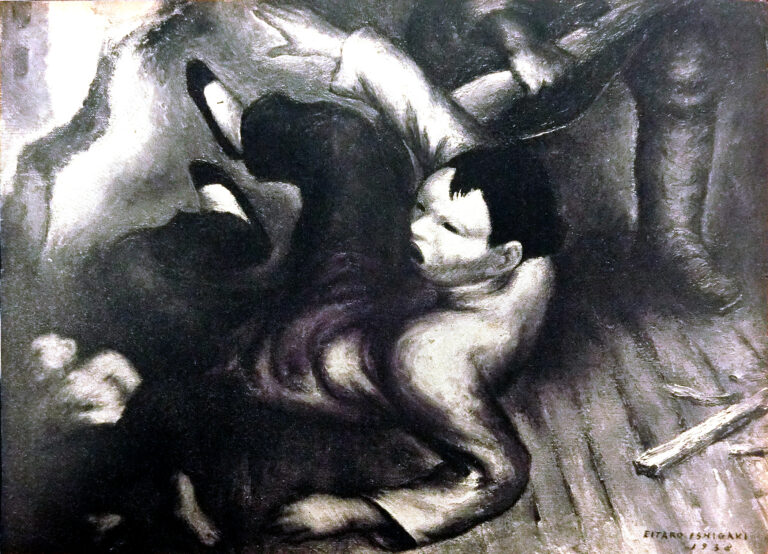

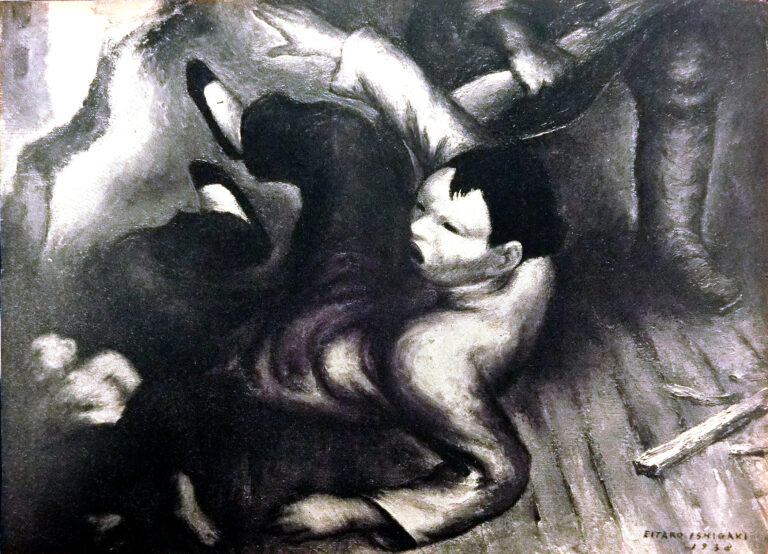

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1923

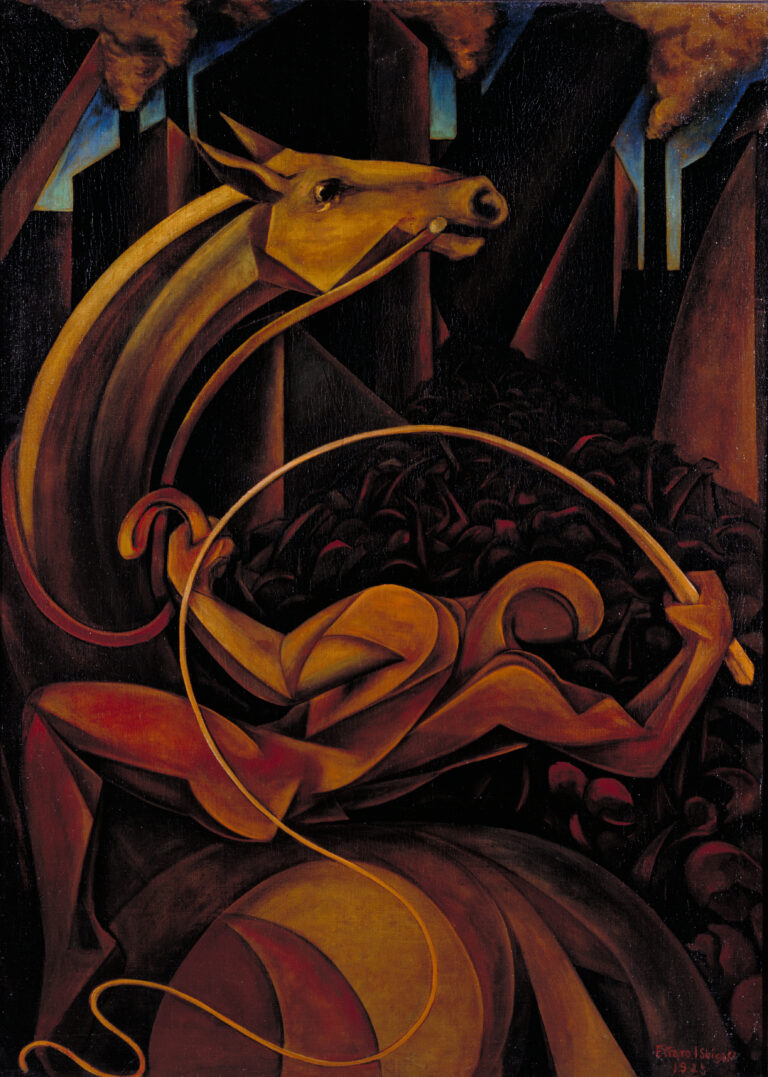

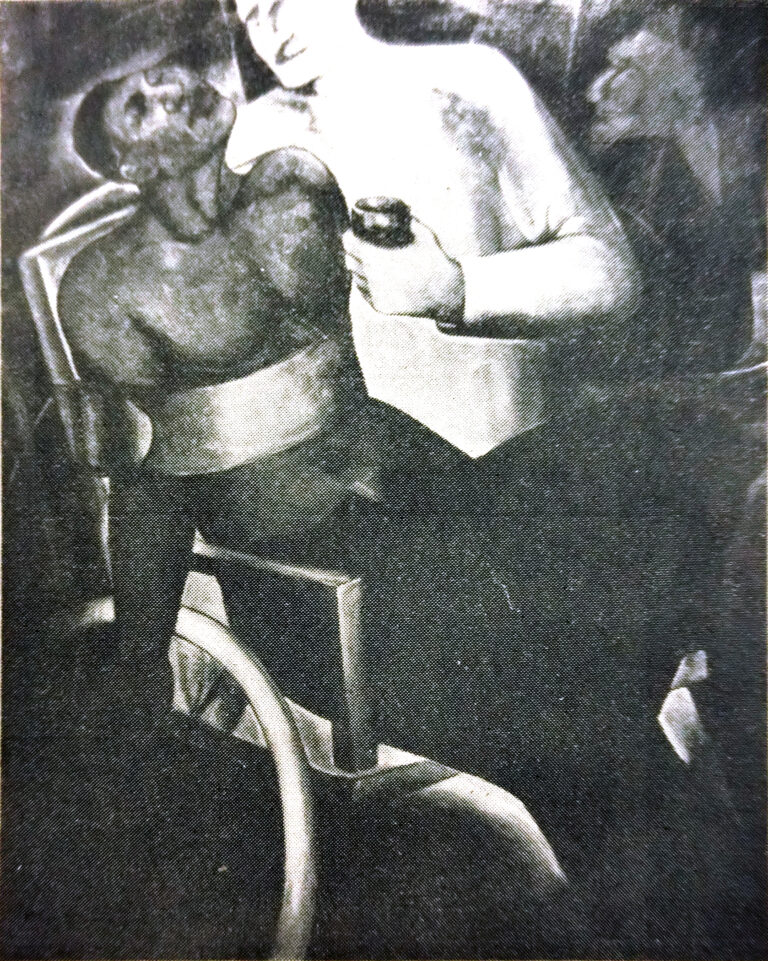

Ch. 3, Fig. 27

Eitaro Ishigaki, Whipping (The Man With a Whip, Whip), 1925 (1295 Independent Artists Exhibition)

“The Man With a Whip, Whipping” depicts a man riding ahorse and wielding a whip against a background ofsmoke-spewing buildings, using curving lines. In thebackground, a group of people are being chased away from their homes. (“The World of Art: Independent Artists and Others”, Times,1925 March 15) Among the exhibitions by Japanese artists, the one makingthe most striking impression was “Man with a Whip” byEitaro Ishigaki. One could say it has caught the “Americanrhythm” with its repeating curves and the snap into tem ofacute angles. The American rhythm is not yet ready foranalysis or classification or illustration, but this Japaneseartist certainly has put grace and strength into the cubisticform of his rider, a curling force into the lash of his whip,fiery animation into the head and elongated neck of hishorse. Orderly pecked excitement into his crowd, a senseof energy controlled and the beauty of controlled energyinto his whole composition—and that is enough for the firstimpression of any picture. (“The World of Art: Independent Artists and Others”, Times, 1925 March 15. ) The New York Shimpo, on the other hand, wrote, “I drewthis picture inspired by Marx’s theory of the class struggle.”(Eitaro Ishigaki, “Colorful Art Exhibition: Sixteen JapaneseExhibitors Boldly and Freely Radiate the Sting andIndividuality of Vigorous Vitality and Strong Colors,” NewYork Shimpo, March 11, 1925).

Image Source:

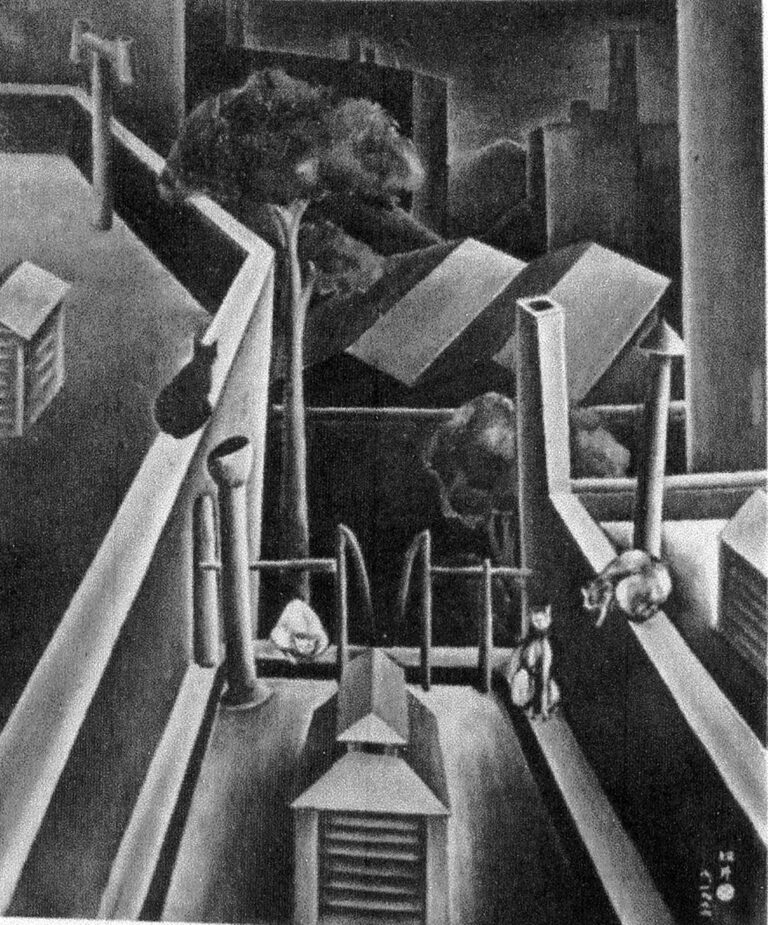

Ch. 3, Fig. 28

Bumpei Usui, Roof at Evening, c. 1925 (Independent Artist Exhibition, 1925)

This painting portrays a view of a rooftop at night. Thestraight lines of the rooftop and chimney are the basicelements of the painting, and four cats are seen standingon the roof. The Nichibei Jiho wrote, “The subject matter is rich inemotion, with a particularly romantic feel with the cats onthe rooftop. The sequential color tones and highly stylized brushstrokes are a delightful and delicate work that will give anyone a pleasant sensation.” (Torajiro Watanabe, “Looking into the 9th Independent ArtExhibition,” Nichibei Jiho, March 21, 1925).

Ch. 3, Fig. 29

Torajiro Watanabe, L Train New York, c.1925 (Independent Artists Exhibition, 1925)

Torajiro Watanabe exhibited a folding screen at theIndependent Artists Exhibition in 1919, which attractedattention for its East Asian style, but here he seems tohave attempted a cubist rendering. The Nichibei Jiho (The Japan-America Times) reported the artist’s comment, “L Train New York” was intended to depict buildings overlaid like a mountain prison and the cityin the blazing heat of summer, but I regret that it was notvery successful” (Torajiro Watanabe, “Looking at the 9th Independent Art Exhibition,” The Japan-America Times, March 21, 1925).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1925

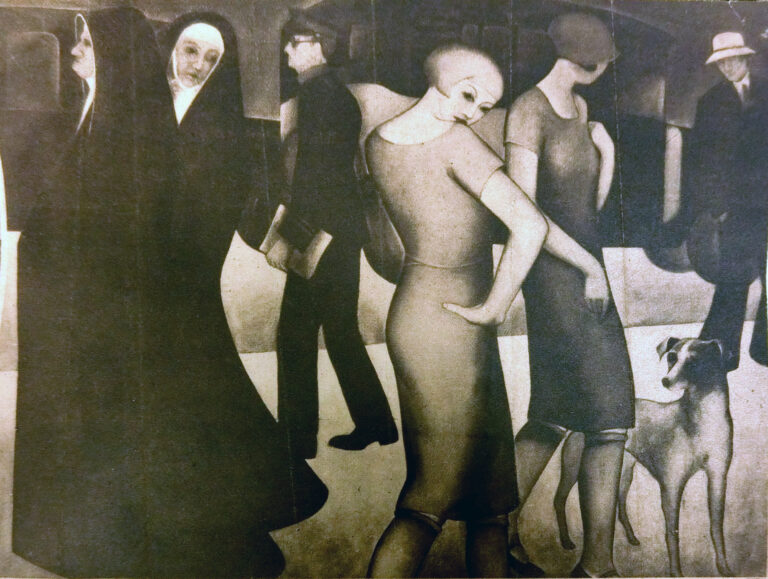

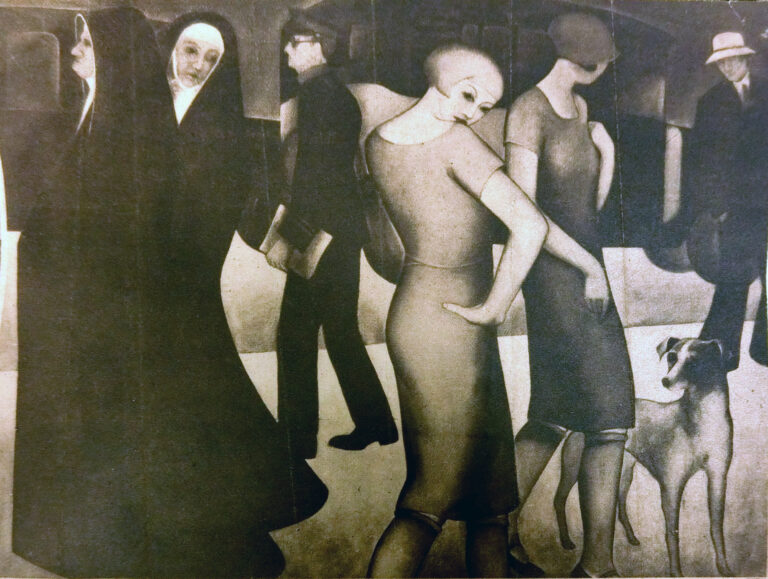

Ch. 3, Fig. 30

Eitaro Ishigaki, Nuns and Flappers, c. 1925 (Salons of America, Fall 1925)

A young girl, known as a flapper at the time, is shownwith a bob haircut and wearing a short skirt andstockings. One of the nuns passing next to her looksback as if to say something as she passes. The girlsymbolizes the glamorous modern culture of the1920s, while the nun is trapped in the tradition,representing the blend of both old and new cultures ofthe time.

Image Source:

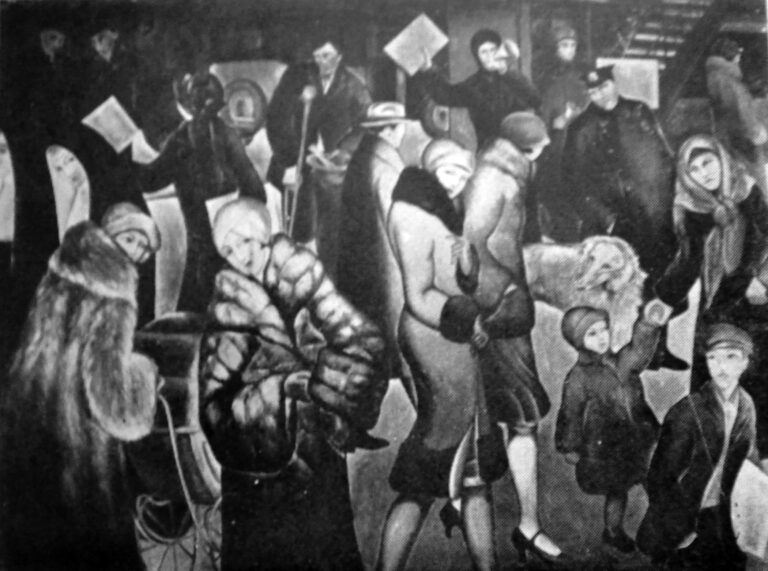

Ch. 3, Fig. 32

Eitaro Ishigaki, Processional, 1925, c.1925 (1926 Independent Artists Exhibition)

Women in fur coats, a girl distributing leaflets, a nun,and a figure on crutches can be seen in thebackground. A young boy selling newspapers is on thefar right, depicting the New York City of that time,where people from all walks of life came and went.The left half of the work is now in the collection of theMuseum of Modern Art, Wakayama, while the right halfis in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art,Kanagawa. The Nichibei Jiho (Japan America Times) wrote, “Theprocession of anonymous people standing quietly onthe street of 14th Street is a manifestation of thefalseness of human life. The painstaking arrangementof the figures captures excellence in both techniqueand color without regret” (Noboru Fujioka, “Dokuritsu Bijutsu Tenjin Zairyo Bijutsu Tenjin Zairyo” [Eleven Japanese Artists from theCord Area Exhibited at the Independent Art Exhibition],The Japan-America Jiho, March 13, 1926).

Ch. 3, Fig. 33

Eitaro Ishigaki, Street *Left Panel, 1925 (1926 Independent Artists Exhibition)

Women in fur coats, a girl distributing leaflets, a nun,and a figure on crutches can be seen in thebackground. A young boy selling newspapers is on thefar right, depicting the New York City of that time,where people from all walks of life came and went.The left half of the work is now in the collection of theMuseum of Modern Art, Wakayama, while the right halfis in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art,Kanagawa. The Nichibei Jiho (Japan America Times) wrote, “Theprocession of anonymous people standing quietly onthe street of 14th Street is a manifestation of thefalseness of human life. The painstaking arrangementof the figures captures excellence in both techniqueand color without regret” (Noboru Fujioka, “Dokuritsu Bijutsu Tenjin Zairyo Bijutsu Tenjin Zairyo” [Eleven Japanese Artists from theCord Area Exhibited at the Independent Art Exhibition],The Japan-America Jiho, March 13, 1926).

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 34

Eitaro Ishigaki, Street *Right Panel, 1925 (1926 Independent Artists Exhibition)

Women in fur coats, a girl distributing leaflets, a nun,and a figure on crutches can be seen in thebackground. A young boy selling newspapers is on thefar right, depicting the New York City of that time,where people from all walks of life came and went.The left half of the work is now in the collection of theMuseum of Modern Art, Wakayama, while the right halfis in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art,Kanagawa. The Nichibei Jiho (Japan America Times) wrote, “Theprocession of anonymous people standing quietly onthe street of 14th Street is a manifestation of thefalseness of human life. The painstaking arrangementof the figures captures excellence in both techniqueand color without regret” (Noboru Fujioka, “Dokuritsu Bijutsu Tenjin Zairyo Bijutsu Tenjin Zairyo” [Eleven Japanese Artists from theCord Area Exhibited at the Independent Art Exhibition],The Japan-America Jiho, March 13, 1926).

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 37

Eitaro Ishigaki, TheMusic Hall on 14th Street (Bald Headed Row), 1924 (Salons of America, 1926)

Dancers dancing on stage in the spotlight, musiciansplaying music below the stage, and people watchingfrom the audience seats, representing a glamorous anddecadent 1920s showtime moment.

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 40

Eitaro Ishigaki, Delirium of Eighteenth Amendment, c. 1927 (1927 Independent Artists Exhibition)

The Prohibition Law was enacted in 1920, but on theother hand, there were many bars and taverns thatoperated under the radar, which had the detrimentaleffect of making people dependent on alcohol. Here, adoctor is pictured administering a drug to an alcoholicpatient. It appears to be a work about Prohibition andthe contradictions that existed during that time.The New York Shimpo wrote, “Ten years have passedsince the prohibition of alcohol was enforced in theU.S., and the prohibition officials’ decree, as EmperorShirakawa sighed, ‘The domination of monks, dice, andalcohols can do nothing,’ and everywhere Buckaroosare dancing like mad…The irony of this contradiction isdepicted. The artist’s emotions are exuded in that gloomy atmosphere. (Noboru Fujioka, “DokuritsuBijutsu Ten,” New York Shimpo, March 19, 1927).

Image Source:

Ch. 3, Fig. 46

Eitaro Ishigaki, A Musical Band Out of Work (Ferry Bout Troubadour, Unemployment Band), 1928 (Independent Artists Exhibition, 1928)

In the late 1920s, the film industry evolved from silentfilms to talkies, in which sound plays along with theimages. With this change, the musicians who used toplay along with films in theaters lost their jobs. This filmdepicts these musicians leaving for the city in search ofwork. The development of industrial technology alsomeant that what had previously been routine becameobsolete.

Image Source:

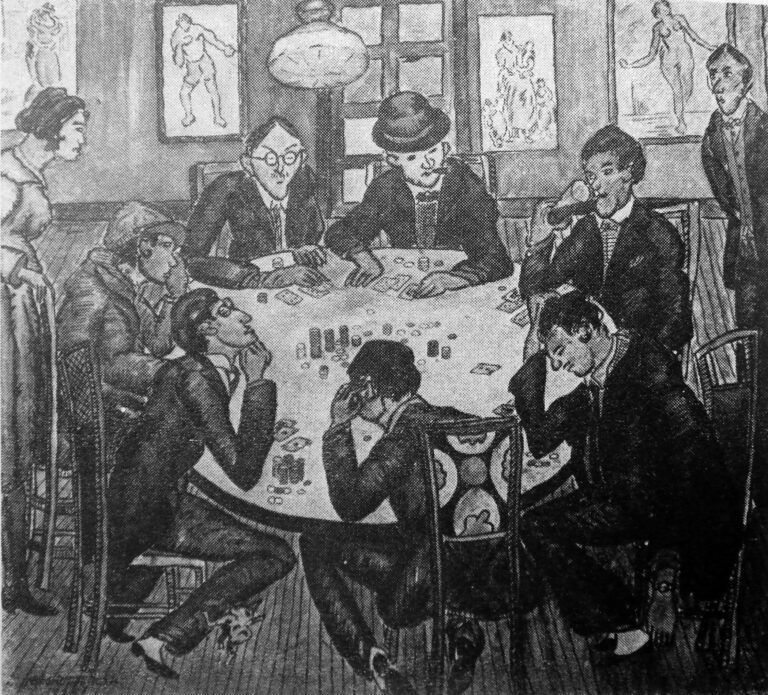

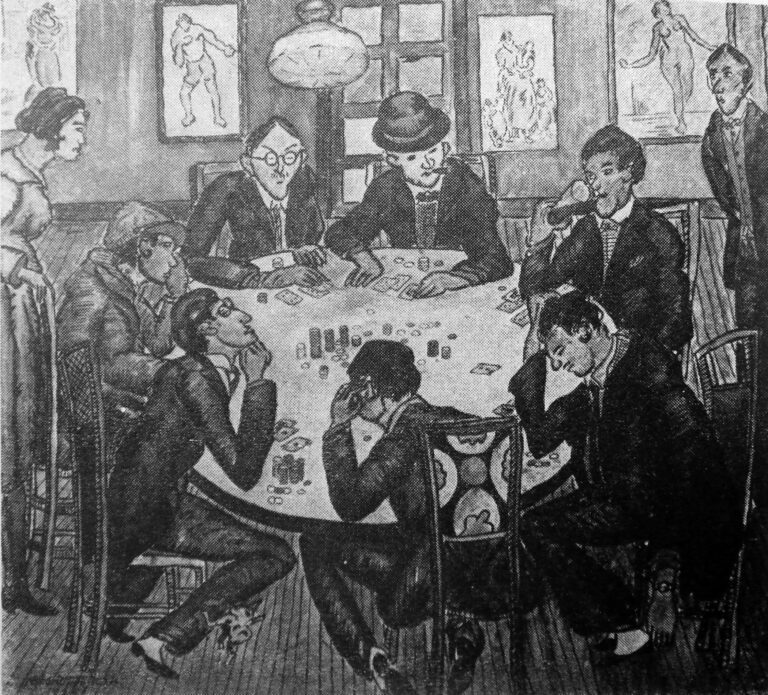

Ch. 3, Fig. 31

Noboru Foujioka, “American Sprit,” c. 1926 (1926 Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists)

“American Sprit,” which was exhibited at the 1926 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, depicts a group of people seated around a round table, absorbed in a game of poker. The man in the upper left corner with glasses looks pleased with himself, while the two figures in the lower right corner are holding their heads in their hands. The people on either side of the table are peering into the game, and the person on the far right appears to be drinking. Against the backdrop of the Prohibition era, this work depicts a room in a black market saloon.In the “Nichibei Jiho” (The Japan-America Times), the artistwrote, “It has been a long time since I came to America, but I have never known what to compare the American spirit to. I have been dreaming about money and meat all the time, and their life is gambling. I tried to express this fleeting emotion in this work. (Noboru Fujioka, ” Independent Art Exhibition, 11 Japanese Painters”, The Nichibei Jiho, March 20, 1926).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1926

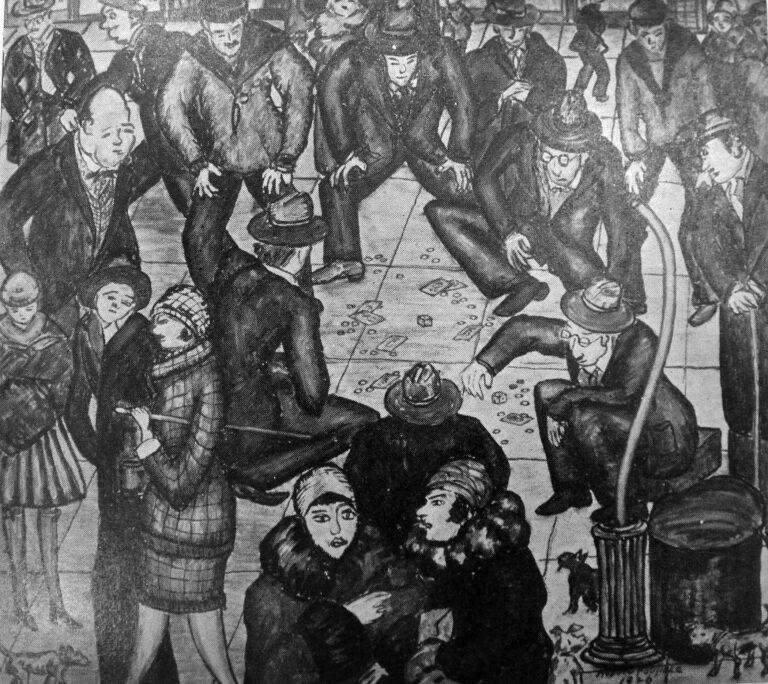

Ch. 3, Fig. 38

Noboru Foujioka, Public Constitution, c.1926 (Salons of America, 1926)

This painting depicts people sitting on the street and playing craps while others watch them with a cold look on their faces. The fur-clad women avoid them and appear to be leaving the scene.

Catalogue of the Salons of America, 1926

Ch. 3, Fig. 39

Noboru Foujioka, Judgement of New York, c. 1927 (Independent Artists Exhibition, 1927)

A flapper is seen in the background, walking with aswagger through the hustle and bustle of New York City,wearing high heels, a fur coat, and a hat. The people around her are also dressed in trendy clothes and seem to be hurriedly crossing the street. The New York Shimpo wrote, “The environment and materials cast a surprisingly diverse range of human characteristics. Noboru Fujioka wrote in his own commentary, “I tried to draw a certain inspiration when I came into contact with a crowd of city dwellers of various shapes and contents, such as adulterers, gamblers, social rebels, nationalist, golddiggers, soulless people, sick people, etc.” (Noboru Fujioka, “‘Independent Art Exhibition’,” New York Shimpo, March 19, 1927)

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1927

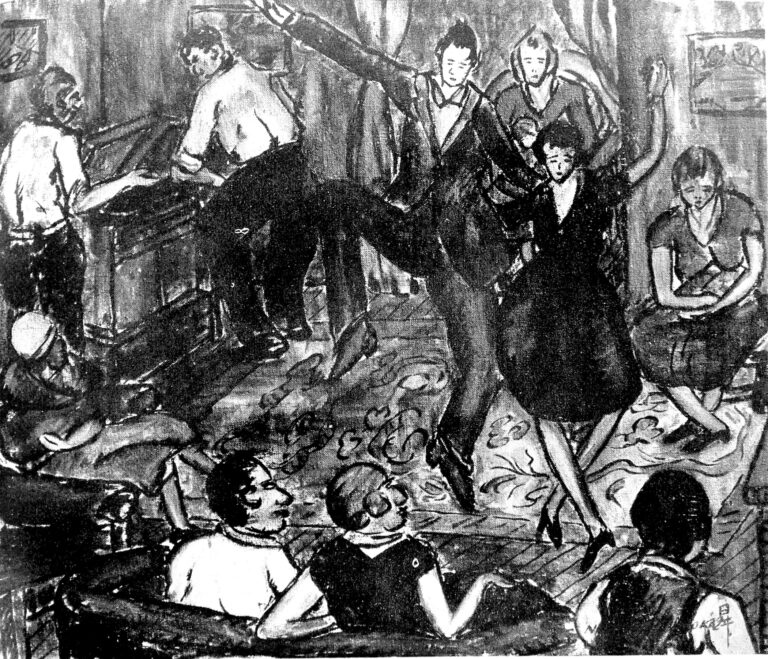

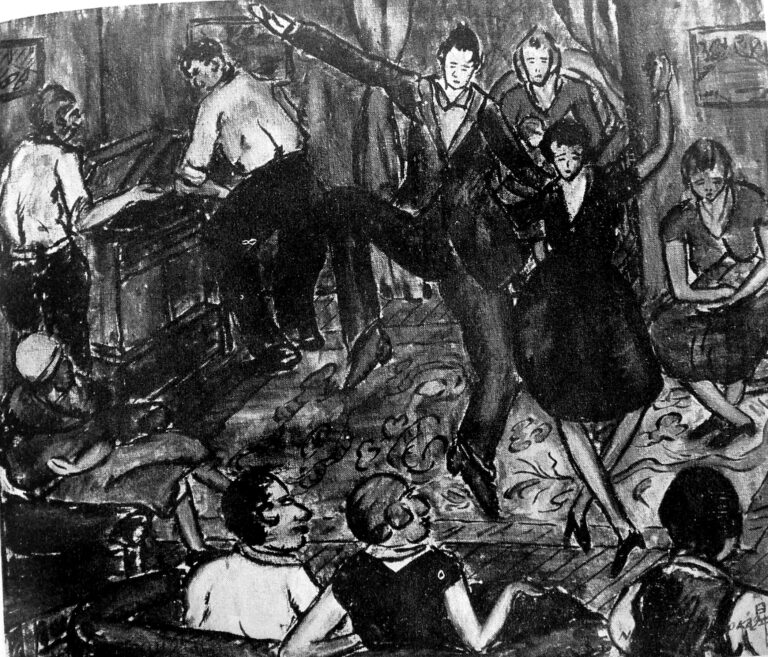

Ch. 3, Fig. 45

Noboru Foujioka, Fraternal Pleasure, c. 1927 (Salons of America, 1927)

The image shows men and women dancing to Black Bottom and Charleston in a bar that illegally operates on the black market. The subject matter of this work is the decadent aspects of Prohibition-era society. The New York Shimpo wrote, “The artist satirically captures the underbelly of society by example. However, it is a success only in terms of its inspiration, and there are points in the painting that do not resonate with me. However, the arrangement of a male and female figure in action on the screen could have been more appropriate, and the objects could have been tied together. I found a certain tone in this work as if I were listening to the music of Jazz.” (Torajiro Watanabe, “Impressions of the Art Exhibition,” New York Shimpo, April 30, 1927)

Catalogue of the Salons of America, 1927

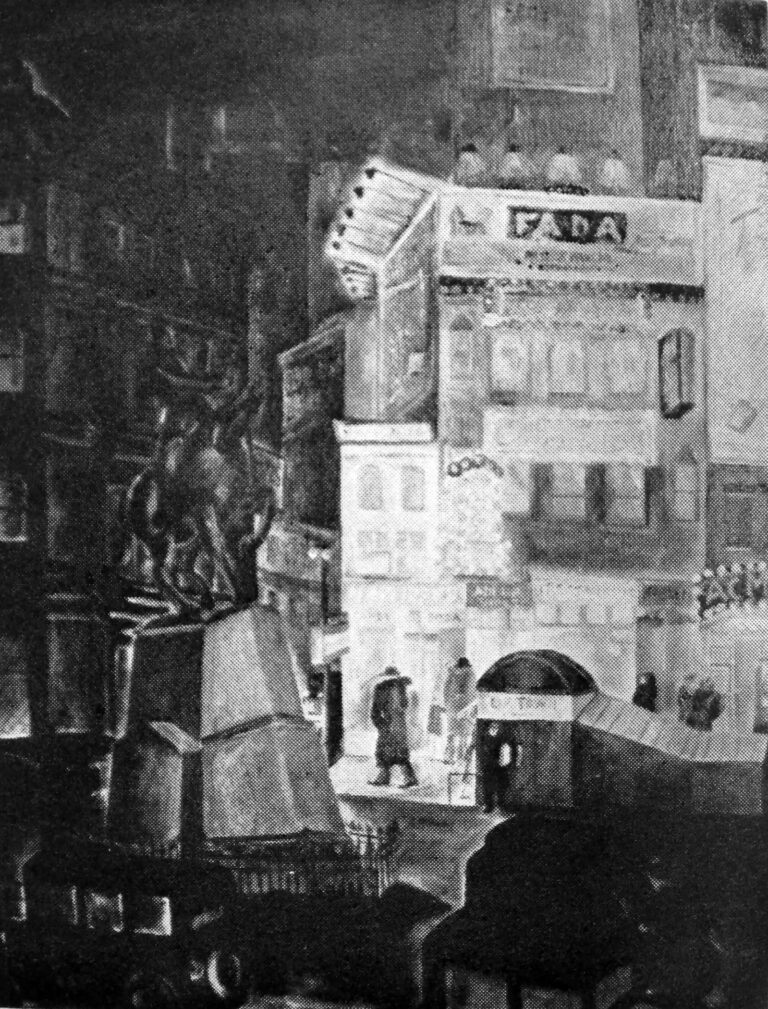

Ch. 3, Fig. 35

Kiyoshi Shimizu, 14th Street, c. 1926 (Independent Artists Exhibition, 1917)

A bronze statue of Union Square stands between thebuildings, with the words “FADA” on the building in thebackground, a figure in an overcoat at the subway entrance, and several cars driving around the square.

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1926

Ch. 3, Fig. 41

Kiyoshi Shimizu, Music Shop, c. 1927 (Independent Artist Exhibition, 1927)

The 1920s was an era of mass production and massconsumption that brought economic and industrialdevelopment. The popularization of radios allowed people to listen to music at their leisure, but at the same time, many people did not have access to radios. These folks probably listened to the music coming from the storefronts. “The “music store” was a place where people could listen tothe sounds of great music anywhere, but we must not forget that there were still many impoverished people in the metropolis who could not afford to listen to the music. The artist’s approach is to depict the scene of such a crowdstrolling in front of a music store in the evening, listening totantalizing music without paying a penny. I think this work is a masterpiece, both in terms of the arrangement of thefigures and the color tones.” (Noboru Fujioka, ” Independent Art Exhibition,” New York Shimpo, March 19, 1927)

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1927

Ch. 3, Fig. 44

Kiyoshi Shimizu, Billiards, Chop Suey and Movies, c.1927 (Salons of America, 1927)

Kiyoshi Shimizu’s works often feature scenes of the city atnight, with countless billboards decorating the entrances tomovie theaters and people passing by.The New York Shimpo wrote, “Kiyoshi Shimizu has awonderful ability to take such a mundane subject matter and make it look noble. If I may make one criticism of your work, it is that it lacks depth and does not suggest depth. It is so bare that it does not give the viewer room for creativity. I would like to see more haiku and zen in your work. (Torajiro Watanabe, “Impression of the Art Exhibition,” New York Shimpo, April 30, 1927).

Catalogue of the Salons of America, 1927

Ch. 3, Fig. 36

Bumpei Usui, Party on the Roof (Summer Evening),1926 (Independent Artists Exhibition, 1926)

This painting depicts a couple enjoying a cool evening on arooftop on a hot New York night. Although this is during the Prohibition era, whiskey and wine bottles are lying around, as well as a “Camel” cigarette box. Residents of neighboring buildings look on enviously; until the early 20th century, drinking and smoking by women was unthinkable. However, some of the new, open-minded women who emerged in the 1920s, known as “flappers,” drank and smoked openly. The New York Shimpo wrote, “The subject matter andconception of this work are extremely fashionable. It is amixture of variegated and colorful tones and has a Jazz-liketone. The focus of the concept may be a little weak, but thisis a common problem with such a subject matter. I don’tthink it is a fine work regarding the painting as a whole.”(Torajiro Watanabe, “‘Independent Art Exhibition,’” New York Shimpo, March 10, 1926).

Ch. 3, Fig. 50

Bumpei Usui, Summer Afternoon (Sunday Afternoon), 1928 (1929,Independent Artists Exhibition)

Four women are enjoying a picnic under the shade of a treein a park with newspapers on the ground. The box in thecenter has the words “Delicious Milk Chocolate” and detailsof the newspaper article. The New York Shimpo wrote, “An interesting image of fourflappers having a picnic under the shade of a tree in CentralPark, with newspapers laid out in the background, depictingthe ponds and rocks of Central Park as if they were paintedin secret. On the mats of newspapers scattered around thearea, the artist has painted in detail everything from Zeff’sdrawing of a man to a picture of a candy box lid. The cleardepiction of boats and figures on the pond, as well as theindividual grasses, at least in part, detracted from the effectof the painting. If he had used these details on the fourwomen, he would have created a masterpiece of hisgeneration. (Ishigaki Eitaro, “Monks’ Camp: Miscellaneous Thoughts onthe Independent Art Exhibition,” New York Shimpo, March13, 1929).

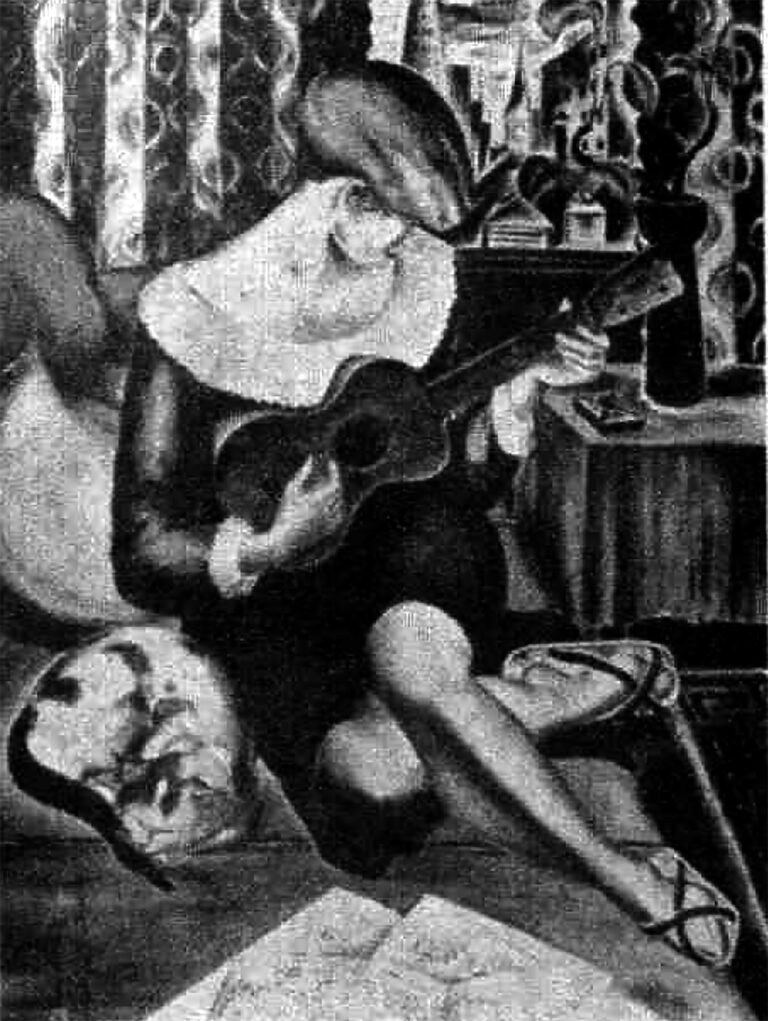

Ch. 3, Fig. 47

Bumpei Usui, Ukulele, c.1928 (1928, Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists)

Bumpei Usui had previously painted several figures on the canvas, but here we see a woman sitting on a sofa playing the ukulele. The Nichibei Jiho (The Japan-America Times) wrote, “‘Ukulele’ is a good picture of Bumpei, whose compositionsare difficult to find a focus, but ‘Ukulele’ has a focus, and therefore is coherent and shows a great maturity of technique. (Eitaro Ishigaki, “The 12th Independent Art Exhibition,”Nichibei Jiho, March 17, 1928).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1928

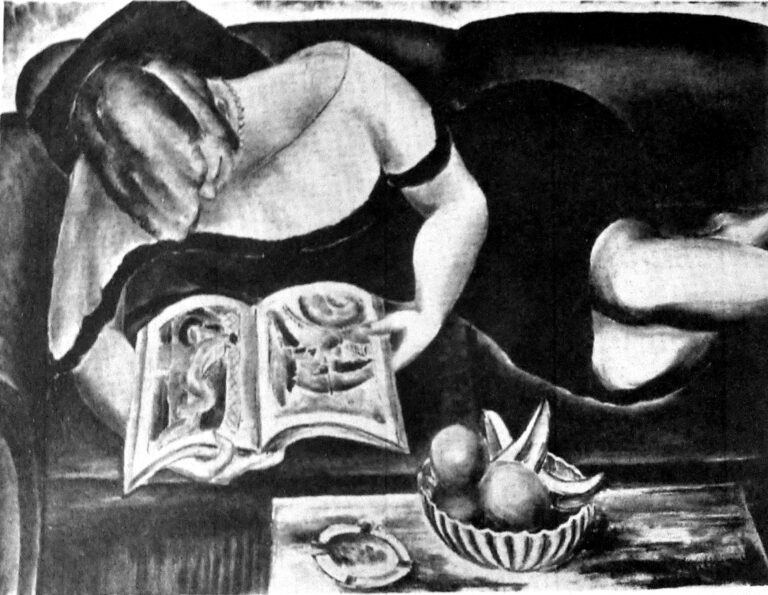

Ch. 3, Fig. 51

Bumpei Usui, Ctalogue, c.1928 (1928, Salons of America)

In “Girl with Cats,” a woman sits on a chair in a room with a Siamese cat, probably his pet, lying on the floor. In contrast to the brown tones of the room, the window in the back right room shows a blue sky and the buildings of New York City.

The Arts, Vol.VIII, No.6, 1928, June

Ch. 3, Fig. 134

Bumpei Usui, Siesta, c. 1929 (1930, Exhibition of the Society of Independent Art)

The “Girl,” created in 1928, depicts a woman wearing a red coat and hat and holding gloves, even though she is indoors, and on the table is a snowy willow in a vase. While Bunpei Usui portrayed aspects of social life interwoven with multiple figures, as seen in “Rooftop Party” and “Summer Afternoon,” these works from the late 1920s focus on a single person, indicating a change in the subject matter of his paintings.

The Arts, Vol. XVI, No.7,1930, March

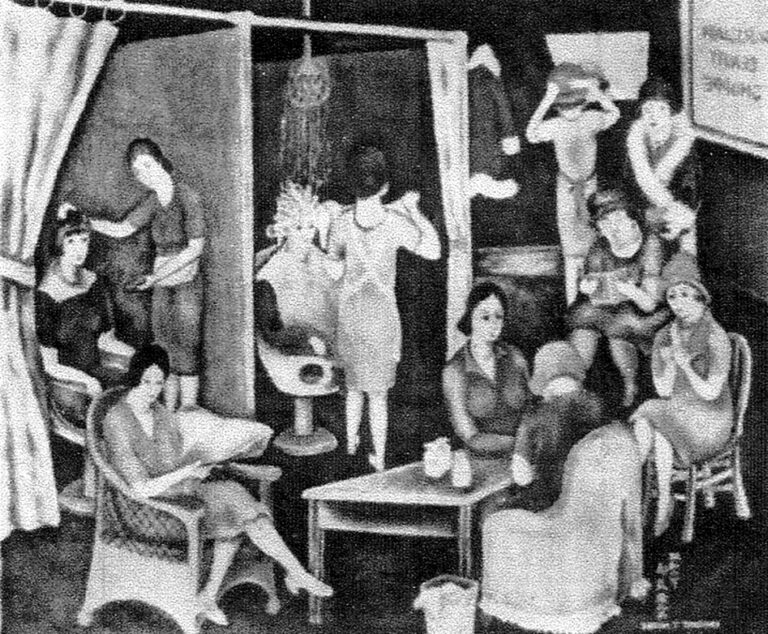

Ch. 3, Fig. 42

Takashi Tsuzuki, Beauty Shop, c.1927 (1927 Independent Artist Exhibition)

This painting depicts women in dresses and hats going to a beauty shop to have their hair cut in the fashionable bob cut of the time. In a private room partitioned off by curtains, the artist depicts them washing their hair in the shower and even getting haircuts in detail.

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1927

Ch. 3, Fig. 43

Torajiro Watanabe, Mob and Persecution, c.1927 (Independent Artists Exhibition, 1927)

A large number of people pass by cars on the street, and acrowd of people gather beside a parked car in the middle ofthe street. Unlike “Symbol of Justice,” with its East Asiansubject matter, and “L Train in New York,” which incorporatescubist techniques, this work by Torajiro Watanabe attemptssocial realism. The “New York Shimpo” wrote, “I believe this is a recentmasterpiece. I hope that this new and innovative approach isthe true spirit of the artist. Considering the arrangement ofthe cars and color scheme, I think it would be a good idea to make the cars more colorful.” (Noboru Fujioka, “‘Independent Art Exhibition’,” New YorkShimpo, March 19, 1927).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1927

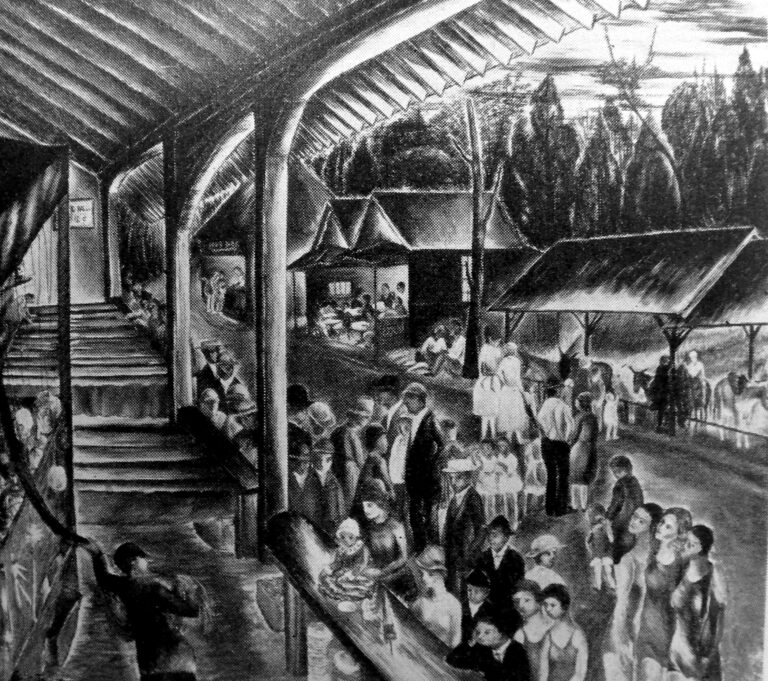

Ch. 3, Fig. 49

Chuzo Tamotzu, Sacandaga Park Midway, c.1929 (1929 Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists)

The background shows an outdoor amusement facility that was open only during the summer months. Children enjoying target shooting, yo-yo fishing, donkey rides, gentlemen in Panama hats, women in swimsuits, and other lively summer activities are the subjects of this painting. The New York Shimpo wrote, “The painting depicts, with alight brush, the summer life of the Japanese in the mountains. The people engaged in activities such as ball games, poker games, and sling games, the red-headed men and women absorbed in these games, the arrangement of the crowds surrounding them, the appearance of the flappers in bathing suits standing among the crowd, the distinction indress and personality between the city people and the country people who frequent the park, are all depicted in his unique color and style. (Ishigaki Eitaro, “Monks’ Camp: Miscellaneous impressions of the Independent Art Exhibition,” New York Shimpo, March13, 1929).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1929

Ch. 3, Fig. 135

Artists gathering Apr. 6, 1928

First row, third from right, Kiyoshi Shimizu, first row, fourth from right, Eitaro Ishigaki, second row, far right, Ayako Ishigaki, third row, second from the right, Bunpei Usui, third row, third from the right, Soichi Kakunan, third row, second from left, Yasuo Kuniyoshi It shows a joyful time of partying with fellow artists.

Private Collection

Ch. 3, Fig. 136

Photo of artists gathering c. 1920s

Although the date is unknown, this photograph was taken at an artist’s party. Eitaro Ishigaki, second row, far left, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, second row, fifth from the left, are shown. These photos show that Japanese artists who studied at the Art Students League in the 1920s had close contact with fellow artists working in New York.

Private Collection

Ch. 4, Fig. 52

A Group Photograph taken at a Japanese exhibition in 1927

Kuniyoshi Yasuo is in the center, Hamachi Kiyomatsu is second from the left in the front row, and Ishigaki Eitaro is on the third from the left in the back row. Bumpei Usui’s “Furniture Factory” is on the far left, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s “Two Women” hanging beside it on the wall.

Ch. 4, Fig. 53

Noboru Foujioka, Charleston, c.1927

The term “Charleston” refers to a type of dance popular in the 1920s, in which dancers performed to jazz music. From the title, we can infer that this work is identical to“Fraternal Prejudice” (exhibited at the Salons of America in 1926), which humorously depicts a man and a woman dancing in a tavern. It depicts the frenzy of nightly partiesheld in black market saloons during the Prohibition era and people dancing to jazz music.

Catalogue of the Salons of America, 1927

Ch. 4, Fig. 54

Noboru Foujioka, American Spirit, c.1926

Shown on the far right in the group photo (Fig. 52) is “American Spirit.” This work was exhibited at the Independent Artists Exhibition in 1926. The New York Shimpo (New York Times) describes the work of Noboru Fujioka as follows, This artist, who abducts people from the street and boldly depicts them, is certainly one of the most unique artists inthe exhibition. He is full of life and vitality. His “The American Spirit” is already well known, and his most skillful use of black color is seen in “Subway Afternoon” and his witty portrayal of human beings in “Charleston.” (Shimizu) The “Subway Afternoon” and “Charleston” have made significant progress. In recent years,” said Shimizu, “the works have become more authoritative, as seen in the American Spirit, which made a stir at last spring’s Independence Exhibition. The works have become richer in both color and content. The gloomy, underground atmosphere is well expressed in his works. While young painters tend to be too candid in their approach, he lacks this, which is why we can say that he has a strong individuality”(Watanabe) (“Review of the Art Exhibition,” The New York Shimpo, February 23, 1927).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1926

Ch. 4, Fig. 55

Masaji Hiramoto, Madame Butterfly, c.1925-1926

Based on the title, we can infer that this work by Shoji Hiramoto is identical to the “Musician” and “Madame Butterfly” exhibited at the Society of Independent Artists exhibitions in 1925 and 1928, respectively.

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1926

Ch. 4, Fig. 56

Masaji Hiramoto, Musician, c.1925

The “New York Shimpo” wrote, “Musician” is better than “Madame Butterfly”. The simplified lines are characterized by Eastern-style conventionalization. (Ishigaki)” Hiramoto’s three works are the ones we remember, but they are always pleasant to look at. I like the first abstract line, because it is quite difficult to draw. (Watanabe)”(“Art Exhibition Review,” New York Shimpo, February 26, 1927), indicating that the work had an established reputation even among Japanese artists.

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1925

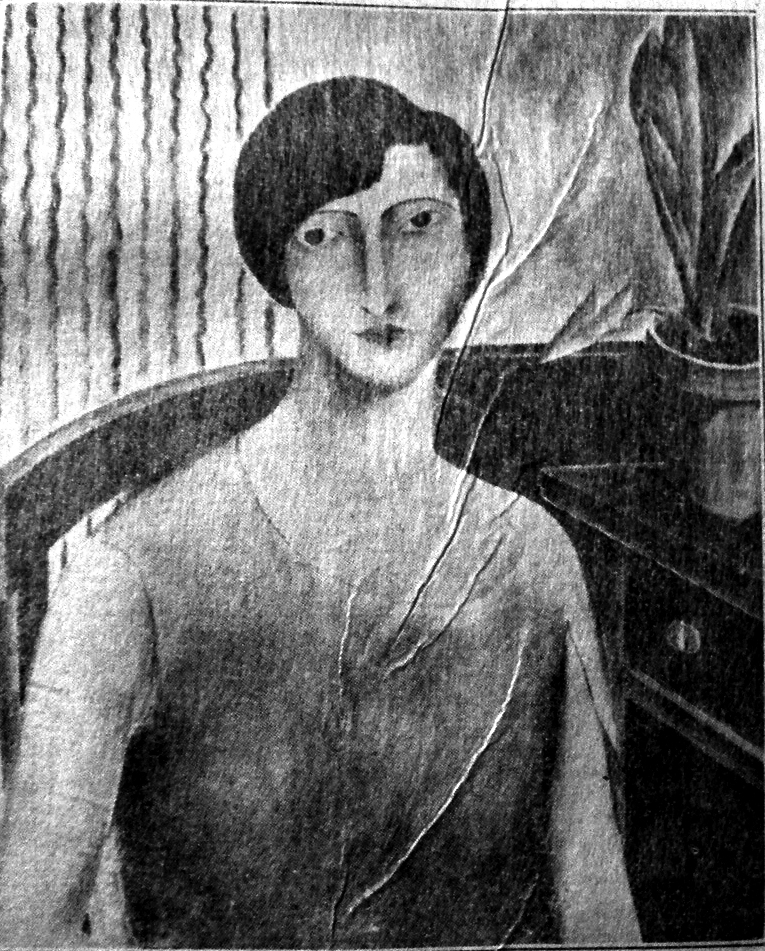

Ch. 4, Fig. 57

Kyohei Inukai, Self-Portrait (Reflection), 1918

This is a self-portrait by portrait painter Kyohei Inukai. This is one of his most famous works, which was also exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1921. The New York Shimpo also noted, “As the standard-bearer of the Academicians, he has already reached the pinnacle of his craft, and it will be interesting to see how his careerdevelops in the future. (Ishigaki) He seems to think he is at the forefront as a painter of the academic school. Look at his bloodless face, he must not be malnourished. (Fujioka) Inukai’s work is probably his best-known work. His coloring and technique are also very skillful. (Watanabe) (“Art Exhibition Review,” New York Shimpo, February 26, 1927)

National Meuseum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Ch. 4, Fig. 58

Eitaro Ishigaki, Nuns and Flappers, c.1925

Eitaro Ishigaki’s “The Nun and the Girl,” also exhibited at the Salons of America in 1925, depicts a flapper and a nun. Fellow artists have praised these works. “He is the onewho has really made a man of this exhibition, “The nun and the girl”, which everyone who comes to the show stops and looks at in silence, is a perfect example of the nun as a saintly figure and the modern flapper who lives a superficial life in pursuit of pleasure. The drawing is not overworked and the colors are clear, which is very good. The “Traffic Conundrum” is one of the best recent works I have seen in this category. There is not the slightest gap. The composition of the bus is very well done, including the green color of the bus and the neat arrangement of the figures. I think this is his best work to date. (Fujioka) When I asked him which of Ishigaki’s works he would like me to buy, he said, “Of course, I would choose “Traffic Conundrum” because the brushwork, coloring anddrawing are all very refined which I found to be his work at first glance. (Watanabe)This artist also uses the shifting of the crowd as his specialty. At least in my opinion, it is a very Japanese style painting. Perhaps it is because of the skillful curves and smooth brushstrokes. Although I have already completed “Traffic Conundrum,” I prefer “The Nun and the Girl” because its clear composition and rational tone of color show the magnitude of the work. I especially like the two nuns, who are very much in the mold.” (Shimizu) (“Art Exhibition Review,” New York Shimpo, February 26, 1927)

Image Source:

Ch. 4, Fig. 60

Kousetu Murata, A Spring Evening, c.1926

Bensetsu Murata was the only female painter among the exhibitors. Although there are many unknown facts about her, she is believed to have temporarily resided in New York during this period, as she exhibited “Rouge” at the Salons of America in 1926. The large work at the top of the group photo is “Spring Evening.” The New York Shimpo wrote, “The colors of the sky and the flowers in ‘Spring Evening’ are good, and the figures have a sense of longevity. It is Japanese inspired by Western painting.” (Ishigaki) ‘Spring Evening’ was selected for the Imperial Exhibition and was very well received. The dreamy mood of ‘Spring Evening’ is well expressed.” (Fujioka) (“Art Exhibition Review,” New York Shimpo, March 5, 1927)

New York Shimpo, 1927 Jan. 1

Ch. 4, Fig. 61

Kiyoshi Shimizu, Fortheen Street, c.1926

This work was also exhibited at the Independent Artists Exhibition of 1926. This exhibition may have allowed the viewer to appreciate this already well-received work once again. The New York Shimpo wrote, “The 14th Street is a goodrepresentation of the night’s mood, especially with the bright lights at night. This is one of the best works by Shimizu” (Ishigaki). The 14th Street was the painting that newspapers and magazines in Tokyo all praised highly at last year’s Independence Exhibition. The 14th Street at night intrigues me in many ways, the composition is notoverdone, and the colors express a unique feeling. […] This is his most representative work, and the mood he has captured as a city dweller is like no other. His soundbrushwork and composition, together with his use of color, make him a household name” (Fujioka) (“Art Exhibition Joint Review,” New York Shimpo, March 5, 1927).

Catalogue of the the Society of Independent Artists, 1926

Ch. 4, Fig. 62

Toshi Shimizu, Yokohama Night, 1921

Toshi Shimizu moved to France in 1924 and was not in New York at the time. This work was included in the exhibition from the George Bellose collection.“Yokohama Night” is a masterpiece and among the best of your peers. (Ishigaki)The night of Yokohama is a perfect example of the murky, gray Japanese culture and urban scene. In many ways, the subtleties of the artist’s worldview and human emotions are expressed without regret in the way he has arranged all kinds of characters among the narrow, dirty streets and irregular houses. (Fujioka) (“Review of the Art Exhibition,” New York Shimpo, March 5, 1927)

Image Source:

Ch. 4, Fig. 63

Soichi Sunami, Portait of My Mother, c.1926

Soichi Sunami, who was also a photographer, studied under John Sloan at the Art Students League and exhibited his oil paintings at the Society of Independent Artists and Salons of America in the 1920s. Three of his paintings, this one depicting his mother in his hometown of Okayama Prefecture, “Nude,” and “Still Life,” wereincluded in this exhibition. The New York Shimpo wrote, “‘My Mother’ was painted from a distant, faint memory, and the nostalgic image of my mother, depicted through the thin brushstrokes of the artist’s hand, reveals a gentle, earnest feeling as an artist. The Nudes and Still Life show the artist’s drawing style. Through these three works, the artist is a person who is progressing, establishing himself in each step of the process. My mother, in particular, has been well received.” (Fujioka) The image of the mother is of exquisite taste, but the Nude and the Still Life show the craft of the artist who has constructed them with a simple touch. The Nudes are fascinating animated figures, and the sense of volume that is unique to the artist is skillfully expressed.” (Shimizu) (“Art Exhibition Review,” New York Shimpo, March 5, 1927).

New York Shimpo, 1927 Jan. 1

Ch. 4, Fig. 64

Takashi Tuzuki, Landscape, c. 1926

This is a work by Takashi Tsuzuki, who studied at the Art Students League and specialized in still life paintings. Two colored flowers in a vase are arranged in a Japanese ikebana-like composition that emphasizes line, space, and depth. Takashi Tsuzuki commented on his creation, “As a Western-style painter when I think of individuality, I am very conscious of my Japanese identity. Eastern philosophies influence my mind and blood, and I am not completely free from religious views of life and literary inspiration, as if I were a blank slate. I want to express the characteristics of my individuality as a Japanese in the richest possible way. (Takashi Tsuzuki, “The Individuality of Art,” New York Shimpo, January 1, 1927). Perhaps this work is a conscious expression of Japanese culture in a Western painting.

New York Shimpo, 1927 Jan. 1

Ch. 4, Fig. 65

Bumpei Usui, Furniture Factory( Machine Shop, Capentors’ Shop), 1925

The work on the far left in the group photo is “Furniture Factory.”This work was exhibited under “Machine Shop” at theSalons of America in 1925. Bumpei Usui traveled aroundthe world with his brother, dealing furniture, and when theystopped in New York City, they fell in love with the areaand settled there. The painting skillfully depicts manyfurniture artisans working at different stages of theproduction process.The New York Shimpo (New York Newspaper) wrote ofBumpei Usui’s work, “The painting of ‘Furniture Factory’ is yourmasterpiece…The figures are scattered apart because ofthe lack of focus, but if you put them together, it is aflawless painting.

Image Source:

Ch. 4, Fig. 66

Bumpei Usui, Portrait of a Girl, c.1926

This is one of the most distinctive works in the gallery.Each of his canvases is filled with the artist’s personalityand gives the viewer an exceptional sense of intimacy.The Carpenter’s Room” is also a masterpiece and atriumph of the artist, but I prefer “Girl,” which is adelightful, effortlessly executed painting. (Shimizu)(“Art Exhibition Review,” New York Shimpo, March 9,1927).

New York Shimpo, 1927 Jan. 1

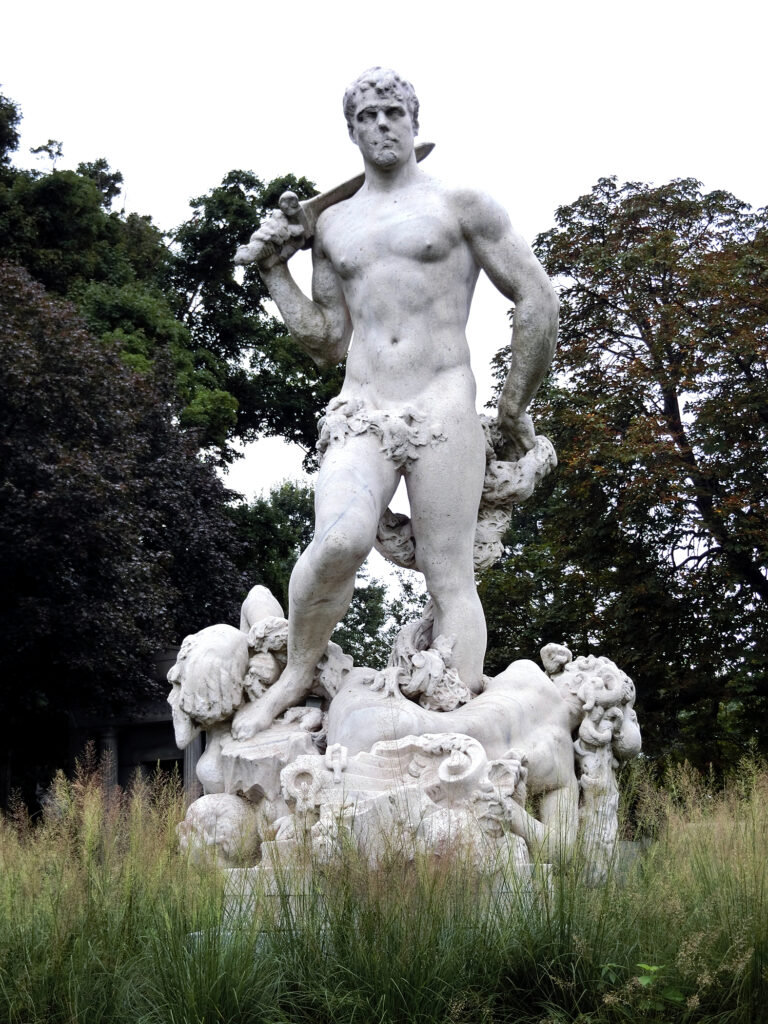

Ch. 4, Fig. 67

Gozo Kawamura, Furederik MacMonnies, c.1926

Gozo Kawamura is a sculptor who studied sculpture at theNational Academy of Design in New York and the Ecoledes Beaux Arts in France. He invented the enlargingsewing machine, a three-dimensional extension machinefor sculpture, and created many sculptures as an assistantto sculptor Frederick William MacMonnies.Gozo Kawamura and MacMonnies collaborated on theworks “Truth” (Figure 137) and “Beauty” (Figure 138) atthe main entrance of the New York Public Library, “CivicVirtue” (Figure 139) in the plaza in front of City Hall (nowinstalled in Greenwood Cemetery), and “The Civic Virtue”(Figure 132) in the Washington, DC area. (now located inGreenwood Cemetery), the “Authority of Law” [Fig. 141] atthe entrance to the Supreme Court in Washington, DC, and the “Contemplation of Justice” [Fig. 142] [Fig. 140].

New York Shimpo, 1927 Jan. 1

Ch. 4, Fig. 137

Gozo Kawamura, Truth, c.1920

The sculpture is installed at the main entrance of the New York Public Library.

Photo: Mai Sato, Guest curator

Ch. 4, Fig. 138

Gozo Kawamura, Beauty, c. 1920

The sculpture is installed at the main entrance of the New York Public Library.

Photo: Mai Sato, Guest curator

Ch. 4, Fig. 139

Gozo Kawamura, Civic Virtue, c.1922

The sculpture was installed in the plaza in front of City Hall and is now located in Greenwood Cemetery.

Photo: Mai Sato, Guest curator

Ch. 4, Fig. 140

Gozo Kawamura, Authority of Law, Contemplation of Justice, c.1935

The sculpture installed at the entrance to the Supreme Court in Washington, DC.

Photo: Mai Sato, Guest curator

Ch. 4, Fig. 141

Gozo Kawamura, Authority of Law, c.1935

The sculpture is located to the left of the entrance to the Supreme Court in Washington, DC.

Photo: Mai Sato, Guest curator

Ch. 4, Fig. 142

Gozo Kawamura, Contemplation of Justice, c.1935

The sculpture installed to the right of the entrance to the Supreme Court in Washington, DC.

Photo: Mai Sato, Guest curator

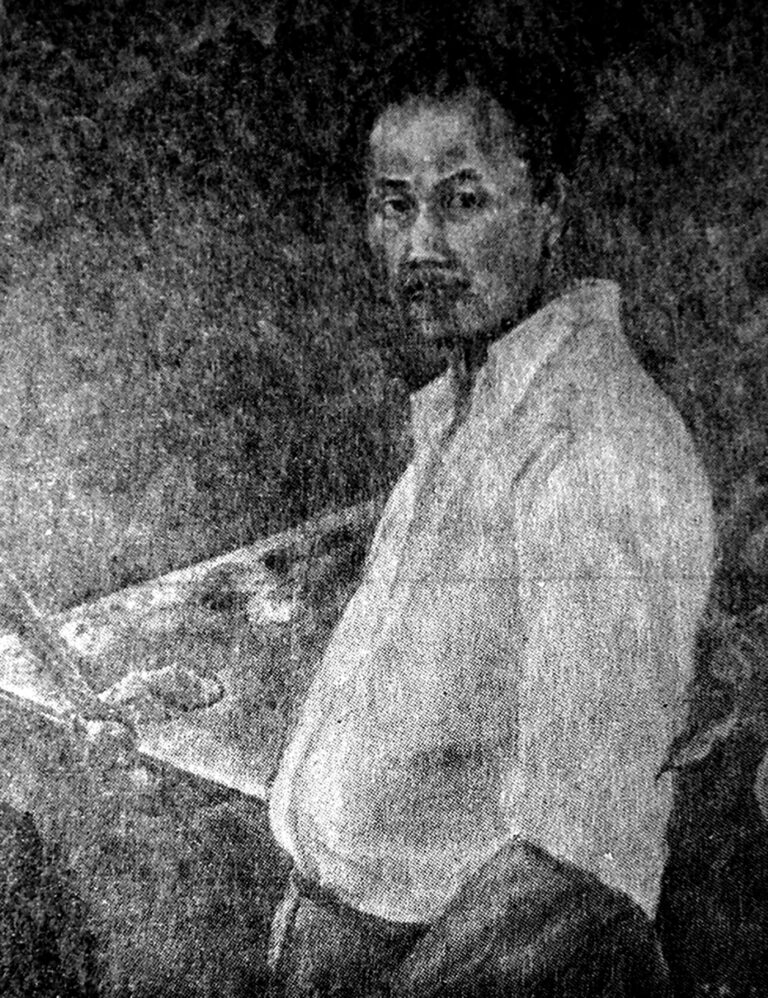

Ch. 4, Fig. 68

Torajiro Watanabe, Self Portrait, c.1926

This painting depicts Torajiro Watanabe posing with apalette in one hand while working on a painting. TorajiroWatanabe has exhibited his works at exhibitions of theAssociation of Independent Artists using varioustechniques, including East Asian folding screens, Cubism,and the Ashcan School. In addition to creating artwork,Torajiro was also a critic who contributed sharp artcriticism to Japanese-language newspapers.“The New York Shimpo,” wrote, “The strong use of color inSelf-Portrait makes it difficult to reconcile the tense facewith the ambient feeling of its surroundings. It gives asense of distance between the face and the body.”(Ishigaki)Self-Portrait was painted in the Woodstock Mountains, andthe artist spent a lot of time and effort carrying brushes, soa man emerges more attractive than it really is.” (Fujioka)(“Art Exhibition Joint Review,” New York Shimpo, March 9,1927)

New York Shimpo, 1927 Jan. 1

Ch. 4, Fig. 69

Sekido Yoshida, East River, c.1927

This work depicts the Brooklyn Bridge over the East Riverusing sumi ink in watercolor style. Hiroshi Saitocommissioned this work, then Consul General of NewYork, in 1925.

New York Shimpo, 1927 Dec. 31

Ch. 4, Fig. 70

Eitaro Ishigaki, Unemployment, c.1932

A man hunches over, clutching a newspaper on a parkbench. In New York City during the Great Depression, thestreets were filled with unemployed people.The New York Shimpo wrote, “Most people who are so out ofwork that they are asleep on the rooftop with a newspaper intheir hands nowadays. Although it may be a bit too gloomy,this is probably closer to what the artist intended.Eitaro Ishigaki’s paintings often show the color of safflower,which is peculiar but generally disliked. However, he has the spirit of a great artist, and I wish he could paint murals.(“Japanese Art Exhibition with Works by Amateur Artists”Nichibei Jiho, February 23, 1935).

Image Source:

Ch. 4, Fig. 71

Thomas Nagai, Interior, c.1935

Plants sprout from potted bulbs on the windowsill, and apeaceful suburban landscape spreads outside the window.

Parunassus,1935,October

Ch. 4, Fig. 72

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Fruits on Table, 1932

Two bunches of grapes and pears are placed on a table.This work was awarded the Temple Gold Medal at thePennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1934.

Ch. 4, Fig. 74

Soichi Sunami, Haystack, c.1935

“Hay Stack” depicts an agricultural scene in autumn, withpiles of straw stacked high against a blue sky. The “New York Shimpo” wrote that “Hay Stack” suggests theeternal nature of heaven and earth, but, regrettably, the colortones have lost their monotonous quality.”(Kiyoshi Shimizu, “Japanese Art Exhibition,” New YorkShimpo, February 20, 1935).

Private Collection

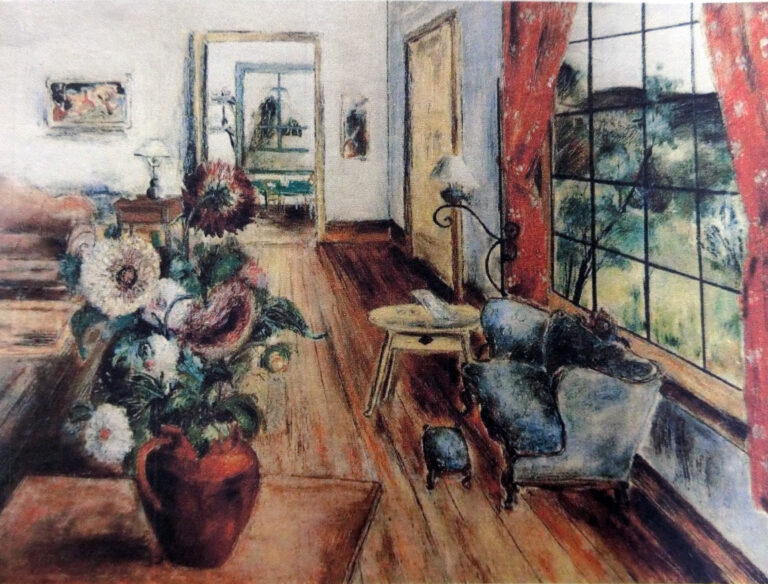

Ch. 4, Fig. 75

Bumpei Usui, Interior, 1934

Many artists gathered in Woodstock, an artists’ village at thefoot of the Catskill Mountains, northwest of New York City, toengage in creative activities. This painting of YasuoKuniyoshi’s house in Woodstock won a prize at theWanamaker’s Legion of Honor exhibition in 1934.

Bumpei Usui, Paintings 1925-1949(Exhibition cataloge), Salander Galleries,1979

Ch. 4, Fig. 76

Bumpei Usui, Landscape, 1932

This painting is a view of the garden from the window ofKuniyoshi Yasuo’s house in Woodstock. Hanging on the wallis a portrait that appears to be the work of Kuniyoshi Yasuo.This painting was included in a 1934 exhibition at theSyracuse Art Museum.The Japanese-language newspaper wrote, “‘Indoor’ is quiteinteresting in how the table and walls are handled, but theshort distance through the glass window is a littleunsatisfying. The “Landscape” is a bit overdone, in myopinion. (Kiyoshi Shimizu, “Japanese Art Exhibition,” New York Shimpo, February 20, 1935) Both “Landscape” and “Indoor” are interesting, although theyresemble Kuniyoshi’s paintings. The works of amateur artistsare also mixed in at the Japanese Art Exhibition, which isinteresting for its uniqueness.” Nichibei Jiho (February 23, 1935).

Fuji Television Gallery, Bumpei Usui, (Exhibition catalogue), 1983

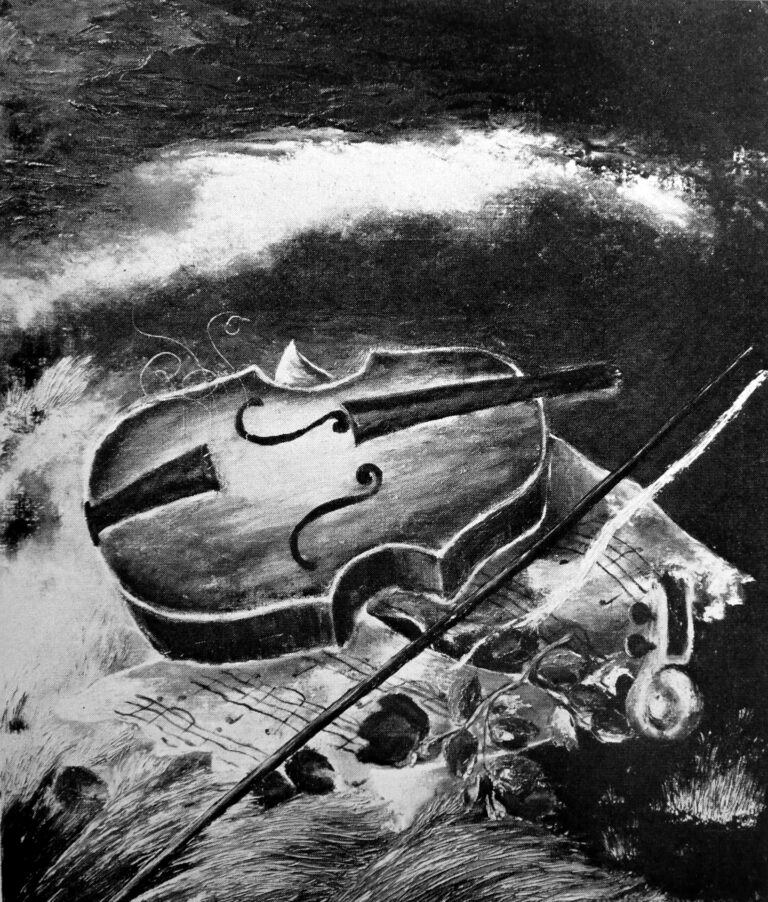

Ch. 4, Fig. 77

Kikuta Nakagawa, Broken Romance, c.1931

A violin on a music sheet. The strings have been plucked,and the cruelly broken tip of the violin and the roses beside itsuggest what might have happened between the two.Based on an art review in the New York Shimpo, it isbelieved that the work in this exhibition is the same still lifethat was exhibited at the Salons of America in 1931.

Catlogue of the Salons of America, 1931

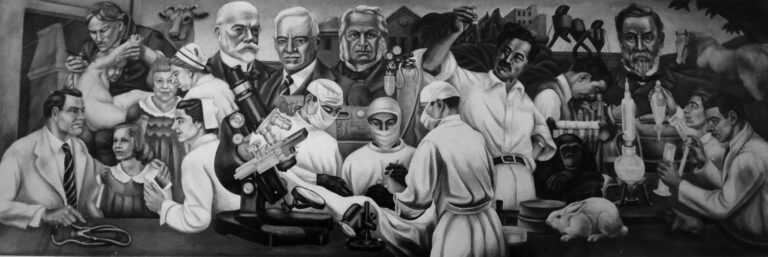

Ch. 5, Fig. 78

Sakari Suzuki, Preventive Medicine, c.1937

Mori Suzuki created a mural at Willard Parker Hospital on the theme of the history of the fight against infectious diseases, featuring Louis Pasteur, Edward Jenner, and Hideyo Noguchi.

Image Source:

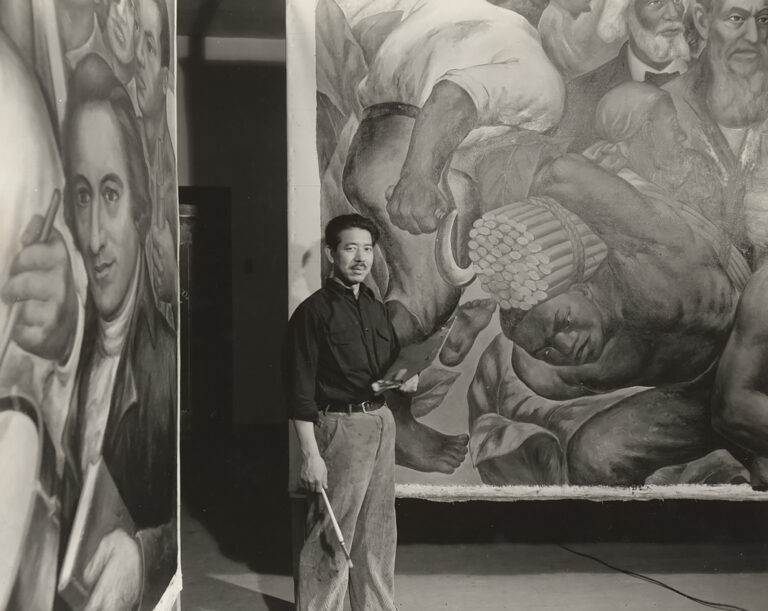

Ch. 5, Fig. 79

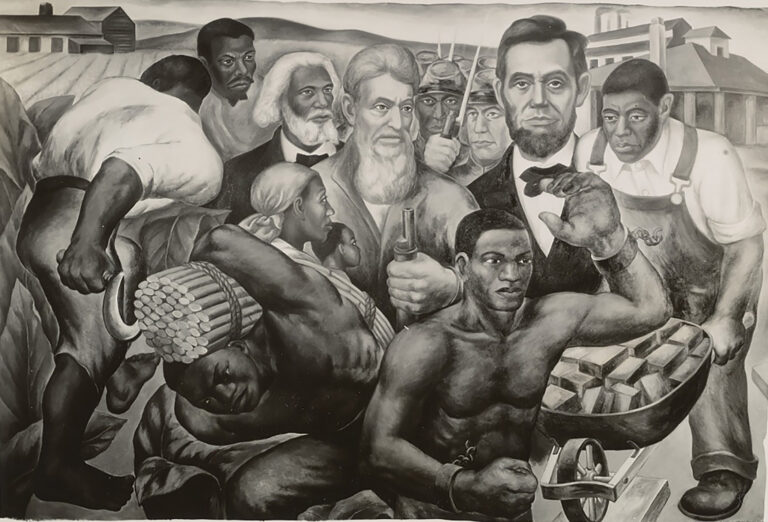

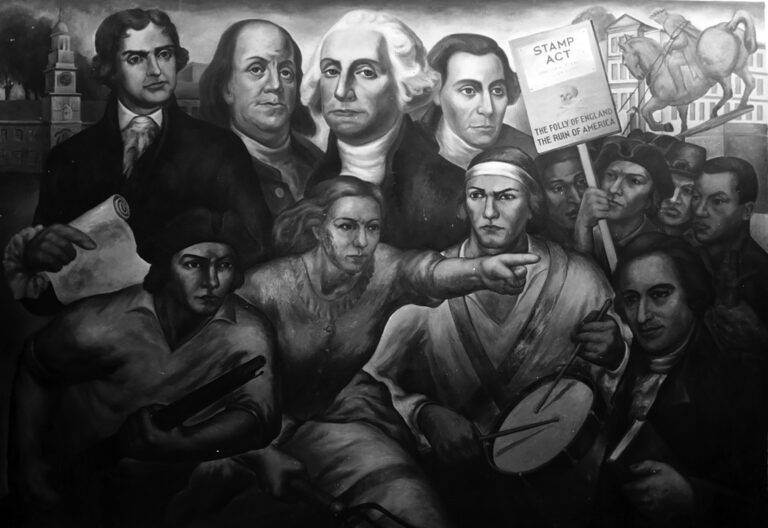

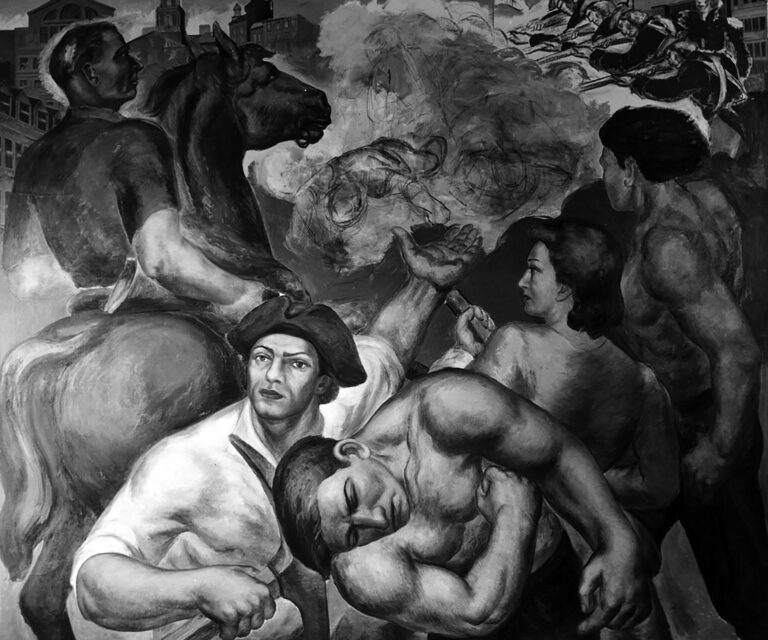

Eitaro Ishigaki, Harlem Courthouse Mural, c.1937-1938

Eitaro Ishigaki worked as the chief muralist for the Harlem Courthouse on 121st Street in New York City from 1935.

Image Source:

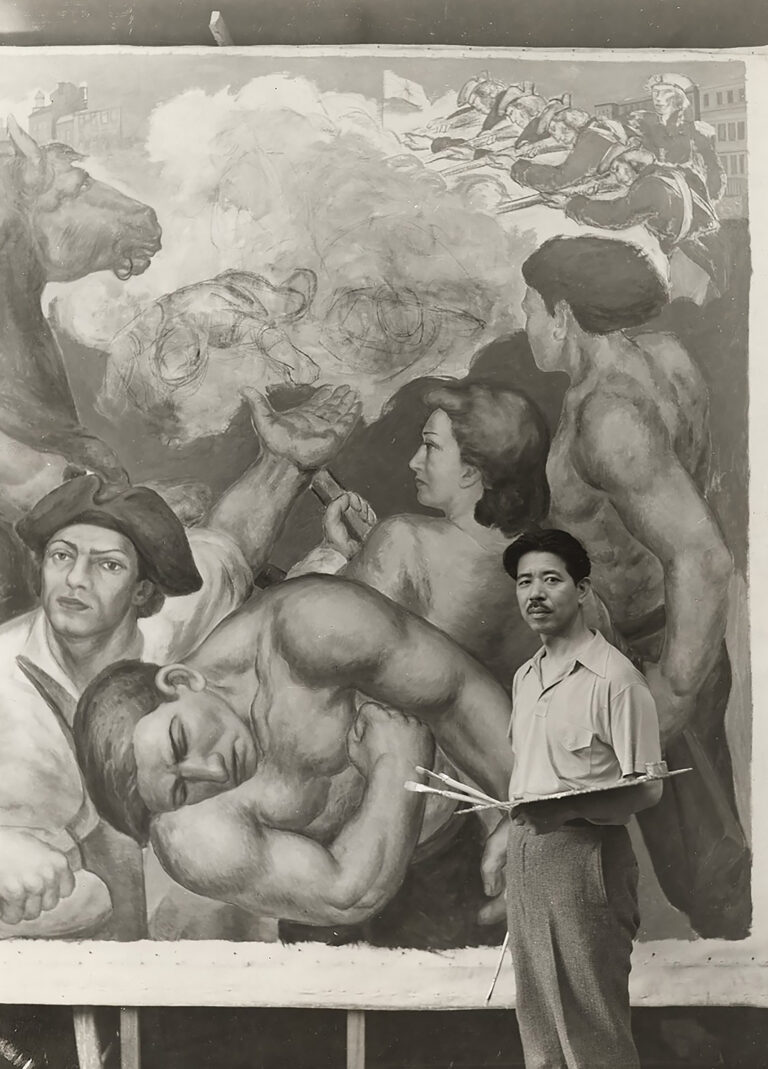

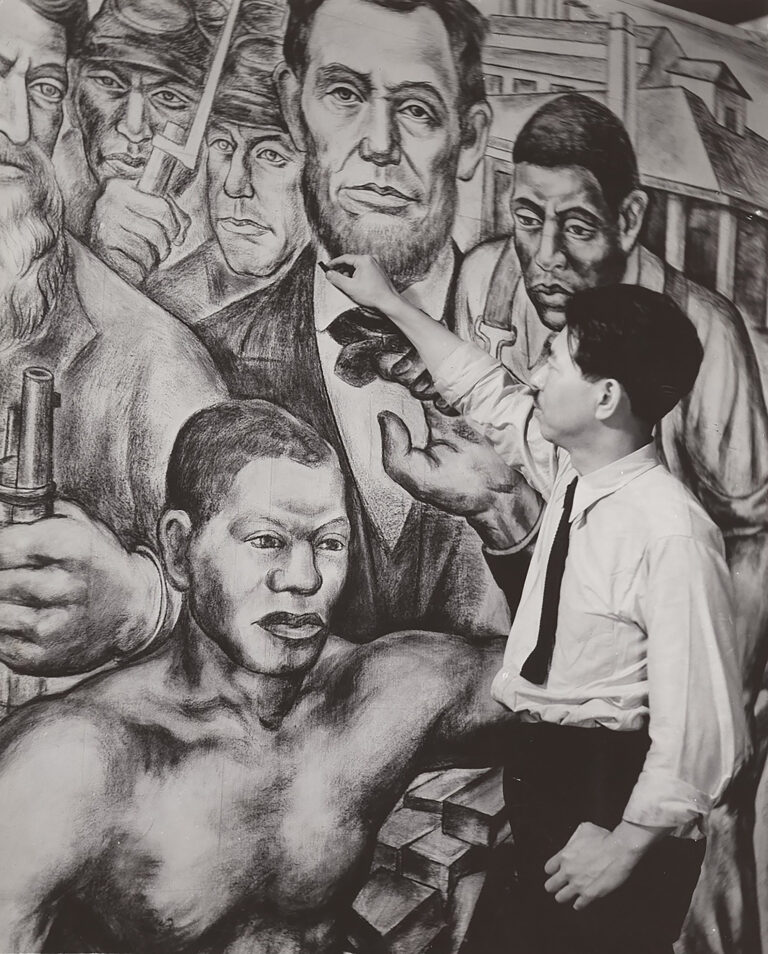

Ch. 5, Fig. 80

Photo of a Mural with Eitaro Ishigaki, c. 1940

The two images are “American Independence” and“Emancipation.” The “American Independence”depicts armed citizens drumming and holding gunsand the portrait of the first U.S. President, GeorgeWashington.

Ch. 5, Fig. 81

Photo of a Mural with Eitaro Ishigaki, c. 1940

Ch. 5, Fig. 82

Photo of a Mural with Eitaro Ishigaki, c. 1940

Ch. 5, Fig. 83

Eitaro Ishigaki’s The Civial War mural at the Harlem Courthouse in New York, c.1937

Ch. 5, Fig. 84

Photo of a Mural with Eitaro Ishigaki, c. 1940

Image Source:

Ch. 5 , Fig. 85

Eitaro Ishigaki, Photo of a Mural, c. 1937

Image Source:

Ch. 5, Fig. 86

Photo of a Mural with Eitaro Ishigaki, c. 1940

Image Source:

Ch. 5, Fig. 87

Yosei Amemiya, Snug Harbor, 1936

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1943

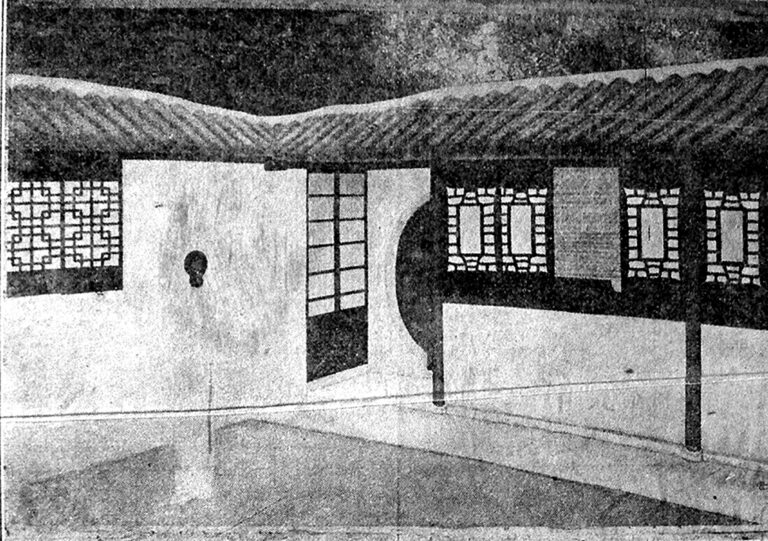

Ch. 5. Fig. 88

Roy Kadowaki, Country Construction, 1936

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1944

Ch. 5, Fig. 89

Roy Kadowaki, Japanese Garden, 1937

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1945

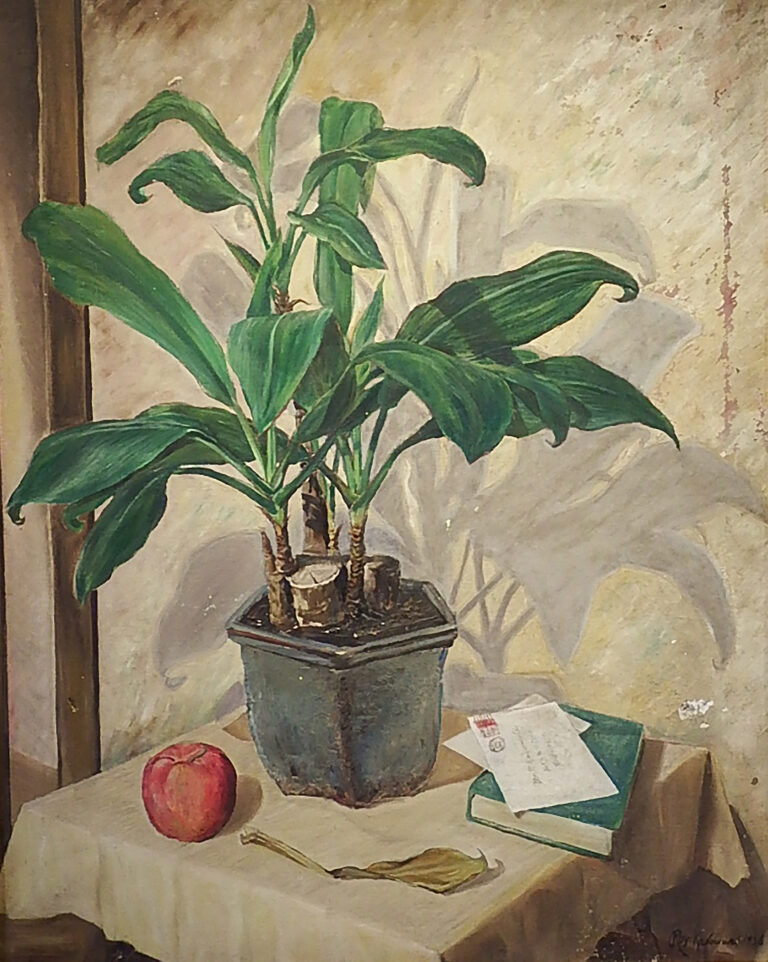

Ch. 5, Fig. 90

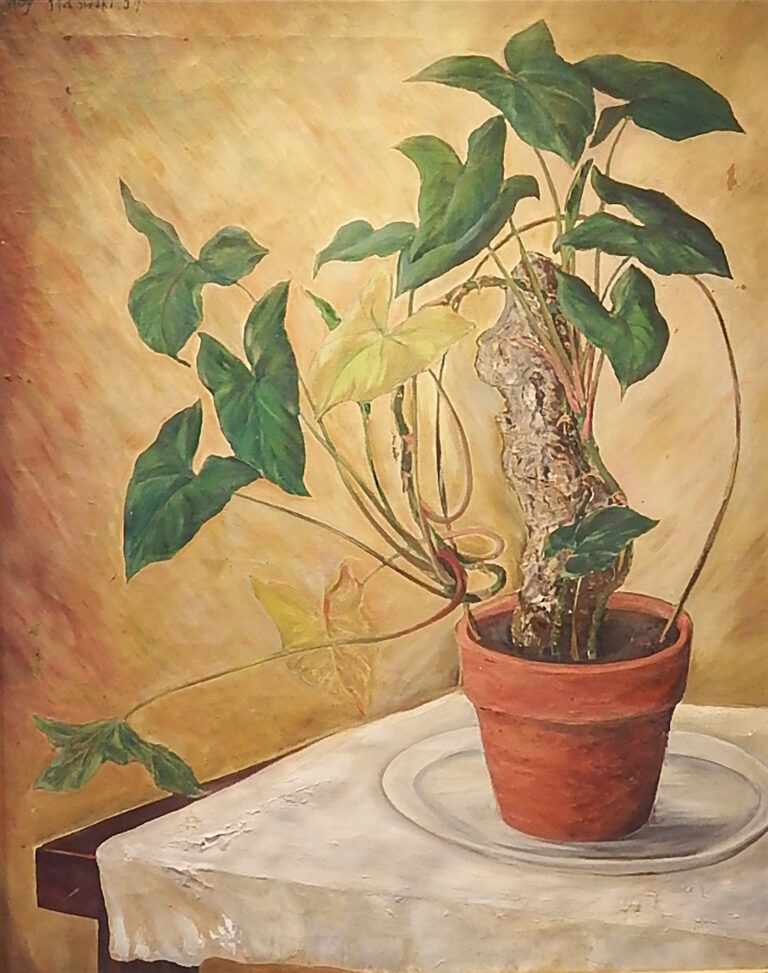

Roy Kadowaki, Japanese Plant, 1936

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1946

Ch. 5, Fig. 91

Roy Kadowaki, Flower Arrangement, 1937

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1947

Ch. 5, Fig. 92

Roy Kadowaki, Flower Still Life, c.1936

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1948

Ch. 5, Fig. 93

Kikuta Nakagawa, House on a Hill, c.1935

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1949

Ch. 5, Fig. 94

Kikuta Nakagawa, Flower Still Life, c.1935

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1950

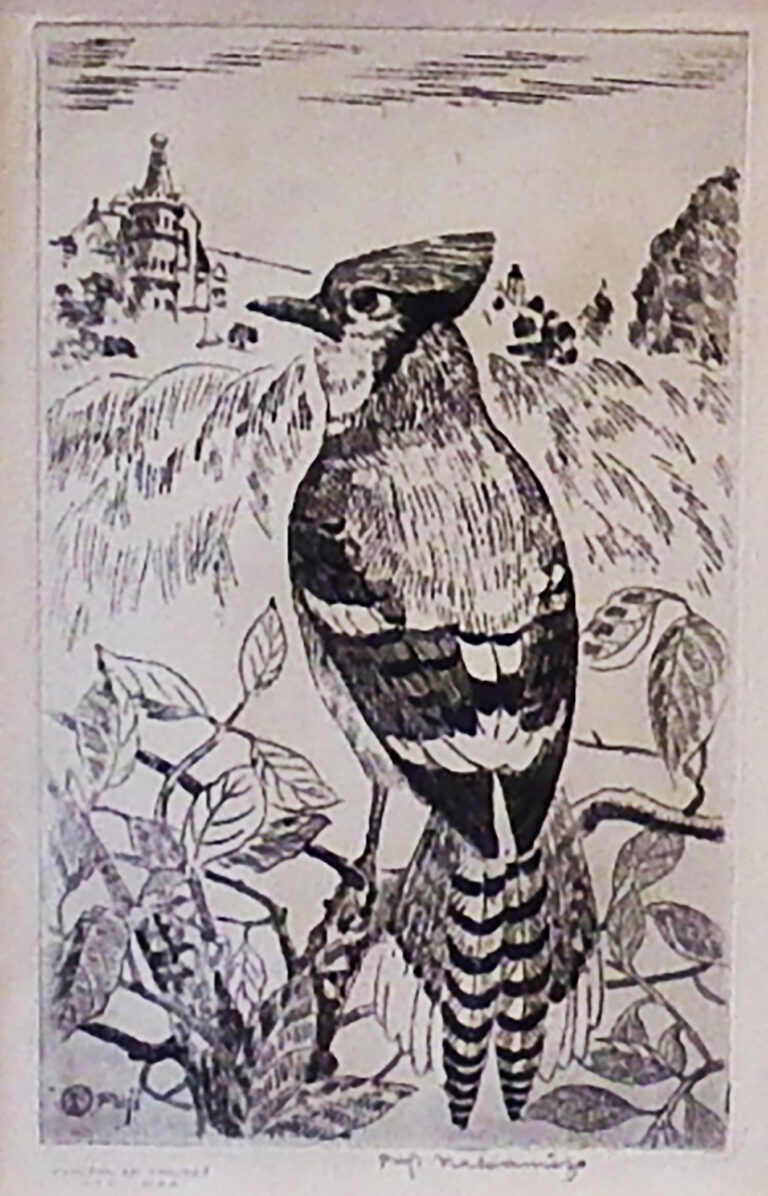

Ch. 5, Fig. 95

Fuji Nakamizo, Wood Pecker, c.1935

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1951

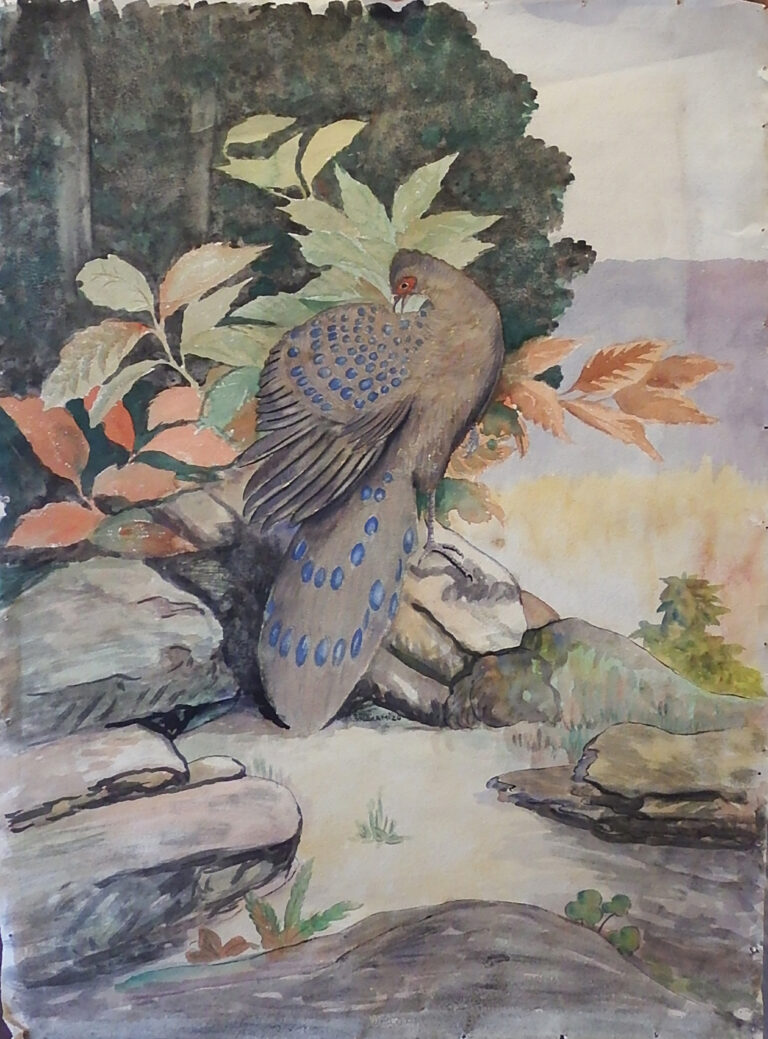

Ch. 5, Fig. 96

Fuji Nakamizo, Peacock Pheasant,c.1935

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1952

Ch. 5, Fig. 97

Fuji Nakamizo, American Wood Cock, c.1935

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1953

Ch. 5, Fig. 98

Thomas Nagai, Small Inlet, c.1935

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1954

Ch. 5, Fig. 99

Thomas Nagai, Greenfields, c.1935

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1955

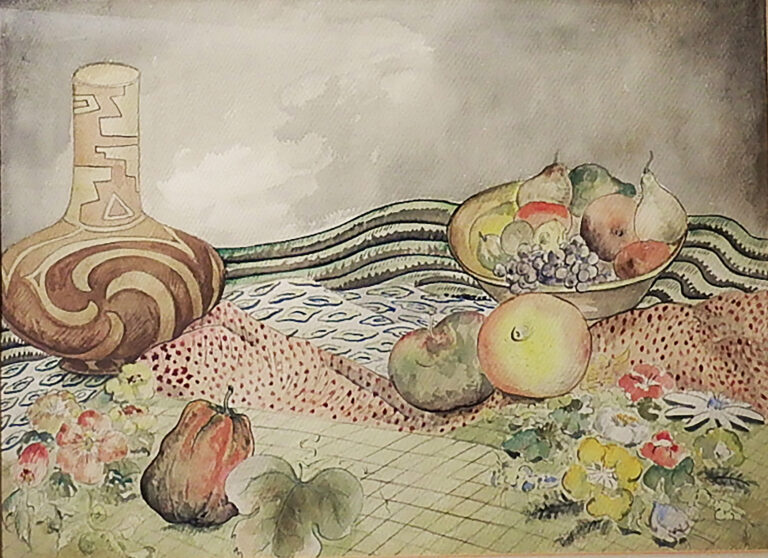

Ch. 5, Fig. 100

Thomas Nagai, Still Life with Figured Cloth, 1936

Genesee Valley Council on the Arts / New Deal Museum, Courtesy of the Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, WPA, Federal Art Project, 1935-1956

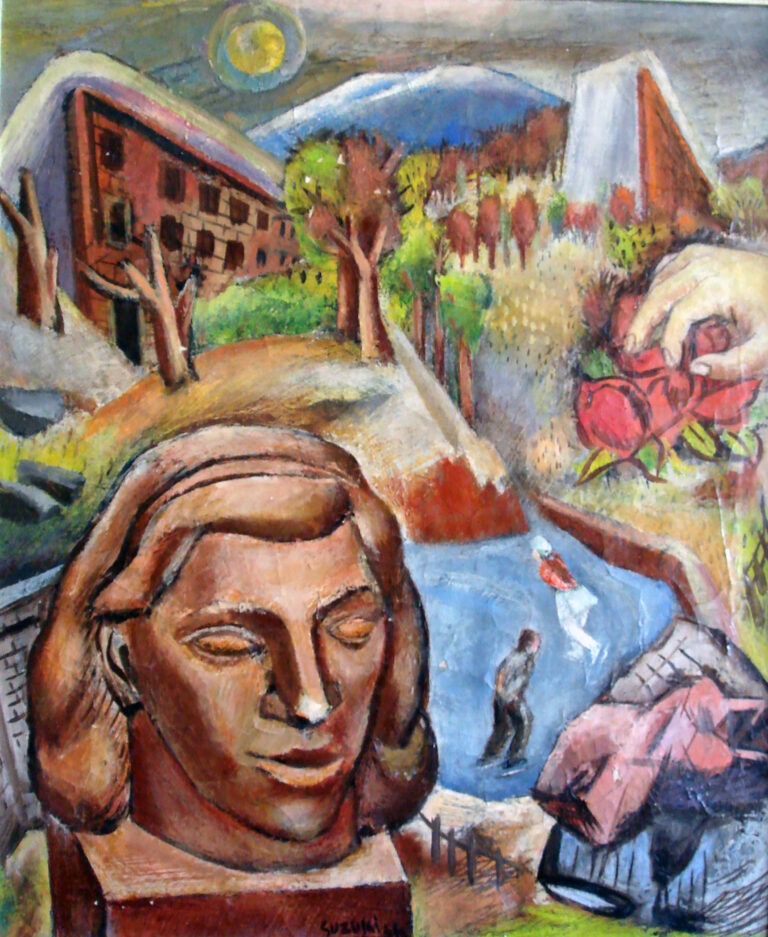

Ch. 6, Fig. 101

Sakari Suzuki, Of Her Past, 1936

A colorful, surrealistic depiction of a person skating behind a giant stone statue and a person’s hand placed on a red flower. This work, “Of Her Past” by Sakari Suzuki, won an award at the first competitive exhibition of the American Artists’ Congress in June 1936.

Private Collection

Ch. 6, Fig. 102

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Odd things on Table, 1935

The painting depicts a black cloth on a table, an overturned vase, a bunch of grapes on a white cloth, a kissel, and several matches on the far right.

Fukutake Collection

Ch. 6, Fig. 103, 104

Eitaro Ishigaki, K.K.K., 1936

This work portrays the persecution by the Ku Klux Klan, a secret society. The tense scene depicts a man tied behind his back and being persecuted, a K.K.K. a member dressed in white chasing him, and another man holding on to him. K.K.K. is identical to a work that was included in the first exhibition of the American Congress in 1937 and in the “Chinese and Japanese Artists in New York” exhibition of the same year.

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Ch. 6, Fig. 105

Chuzo Tamotzu, Fire Trap, c.1937

The background of downtown tenements, laundry floats between buildings, depicting the reality of the lives of ordinary people. The distant skyscrapers of Uptown and the huge tanks on the rooftops of the buildings in the background depict some aspects of the humble life of the downtown area.

Art Front. December, 1937.

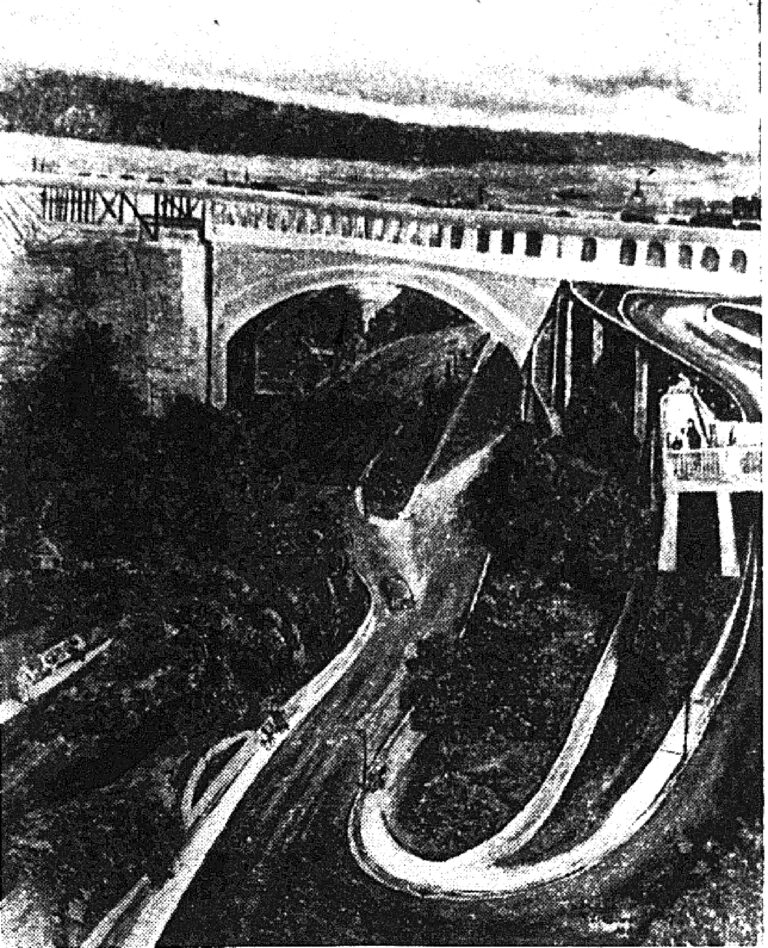

Ch. 6, Fig. 106

Roy Kadowaki, Riverside Drive, c.1938

Based on the title, we can infer this is the same work as the “Hudson River,” exhibited at the 1938 New York City Exhibition. It depicts the George Washington Bridge over the Hudson River, which runs along the west side of Manhattan.

New York Shimpo, 1938,June 15

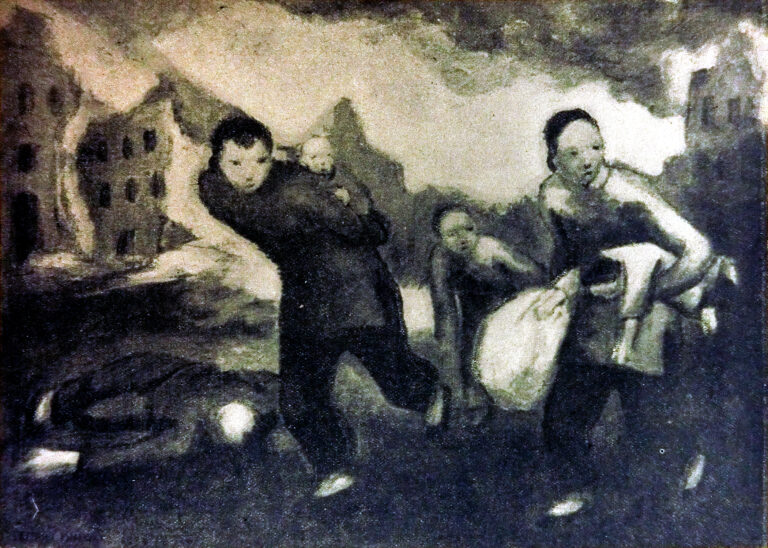

Ch. 6, Fig. 107

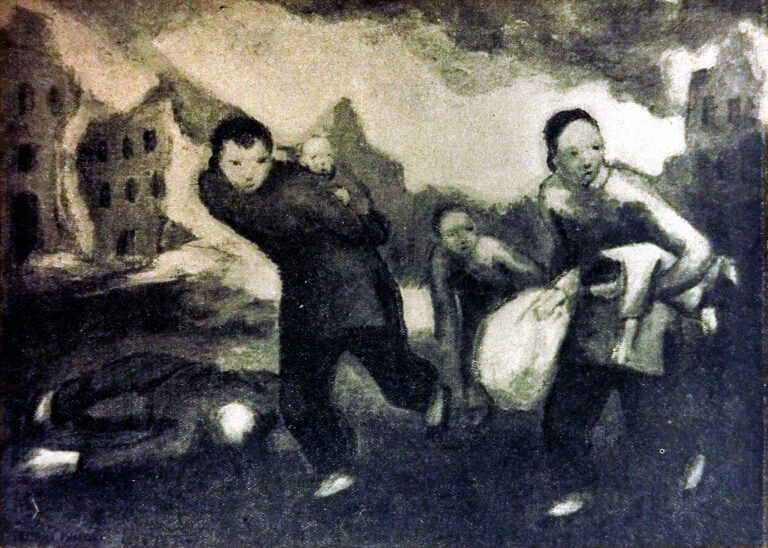

Eitaro Ishigaki, Flight, c.1937

A family fleeing war with a baby in their arms is depicted in the foreground, with a man lying on the street to the left. Based on the people’s clothing, this work is believed to portray an event in China.

Catalogue, Museum of Modern Art Wakayama

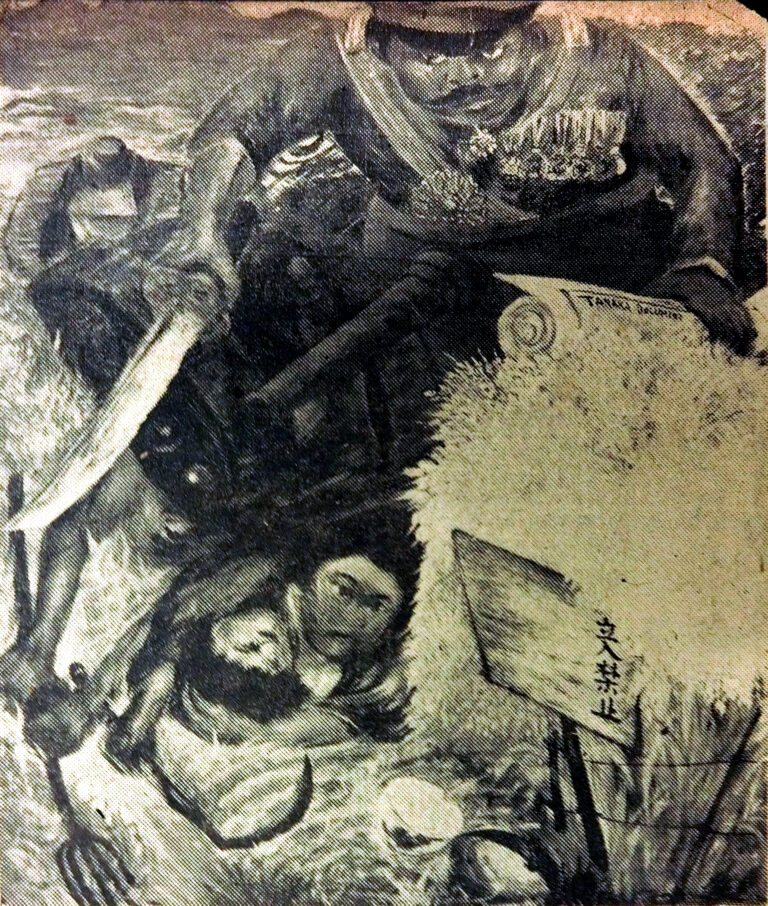

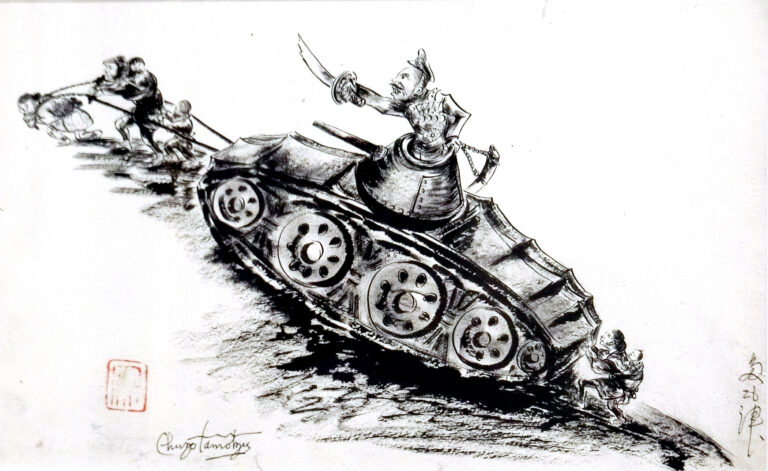

Ch. 6, Fig. 108

Chuzo Tamotzu, Militarism Over Japan, c.1937

This work by Chuzo Tamotsu was run in the New York Post, “A work expressing a strong comment on the war. A Japanese soldier is depicted in the center of the painting with his sword drawn as he chases away the people, while in the right foreground are the words “No Trespassing,” and in the left background is Mt. Fuji.

New York Post. December 14, 1937.

Ch. 6, Fig. 109

Sakari Suzuki, War, c.1937

Sakari Suzuki’s “War” symbolizes war-related objects such as skeletons, helmets, gas masks, and trenches.

Painting "War" by Sakari Suzuki, exhibited at the American Artists Congress, 1937, World Telegram & Sun photo by Alan Fisher

Ch. 6, Fig. 110

Eitaro Ishigaki, Victim of War, c.1938

In the center is a man dressed in Chinese clothing being chased away by a gun, and at his feet is a child lying on the floor. Behind him is a figure in military uniform, possibly a Japanese soldier, standing with a gun.

Catalogue, Museum of Modern Art Wakayama

Ch. 6, Fig. 111

Thomas Nagai, Art Class, c.1937-1938

This work humorously depicts an art class with models.

Catalogue of the American Artists' Congress, 1938

Ch. 6, Fig. 112

Sakari Suzuki, Landscape, c.1937-1938

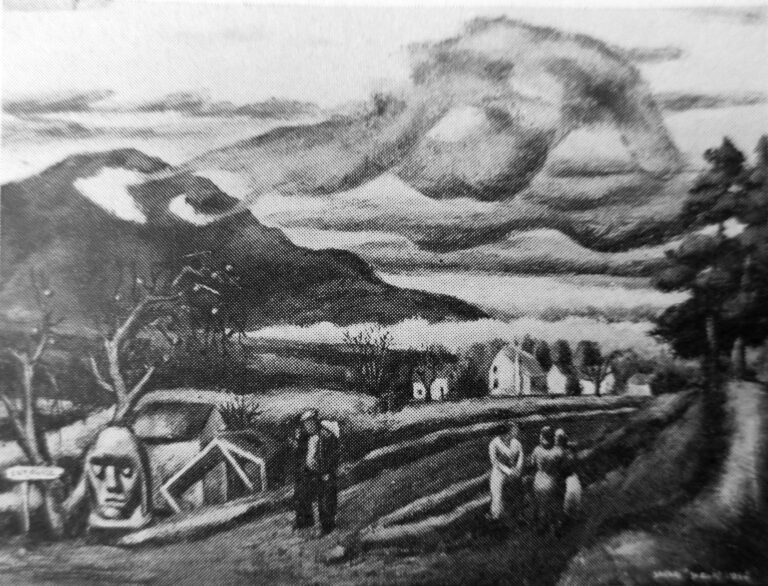

This is a landscape of a suburb of New York City, with mountains and clouds in the sky, figures walking along a country road, and houses in the distance, as if painted on a ceramic ornament. A huge stone head is placed on the far left, which seems out of place in this scene. This is the style of surrealism often used in the works of Sakari Suzuki.

Catalogue of the American Artists' Congress, 1938

Ch. 6, Fig. 113

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Lay Figure, c.1937-1938

Yasuo Kuniyoshi exhibited “Reclining Figure” in this exhibition. The details of this work are unknown at this time, as we have yet to be able to confirm the catalog. Still, Yasuo Kuniyoshi produced another work around the same time, entitled “Lay Figure,” which is very similar to “Reclining Figure.” As has already been pointed out by some review, the magazine between the figure and the chair bears the year “1906,” the same year Kuniyoshi moved to the United States. In addition to the furthermore, newspapers are placed casually on the pale figure, posed in an unstable pose on the chair, which appears to be oppressed by the media that convey information, such as newspapers and magazines. The Figure would collapse from its chair with even the slightest shock. In the United States, from 1937 to 1938, when this work was produced, Japanese artists of the time, including Yasuo Kuniyoshi, were being recognized in the American art world for their achievements, although they did not have citizenship. However, Japanese people without citizenship must have been in a very precarious position in the U.S., where the Second World War was looming large, along with the Sino-Japanese War and accusations of fascism. The figure in this painting can be read as a projection of the place of the Japanese in America in the late 1930s, and “Reclining Figure,” which was shown at an exhibition in New York City in 1938, may have been a work with such a message.

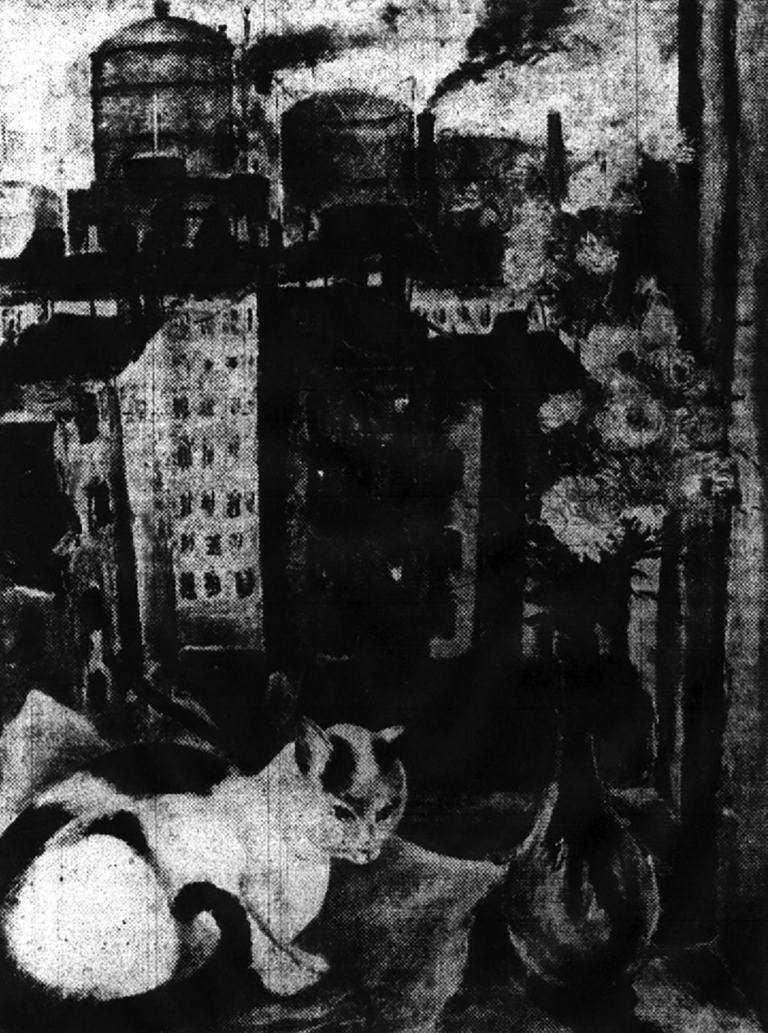

Ch. 6, Fig. 114

Chuzo Tamotsu, Gas Tank and Flowers, c.1938

A vase of flowers on the windowsill, a cat standing next to it, a downtown New York tenement outside the window, and a huge tank on the roof. The composition captures a glimpse of the life of ordinary people in the downtown area. This work is identical to one exhibited at the Second Annual Exhibition of the American Artists’ Congress in 1938.

New York Times. June 26, 1938.

Ch. 6, Fig. 115

Eitaro Ishigaki, Victims of War, c.1938

(Same as Fig. 110.) Ishigaki Eitaro presented these anti-war-themed works from the Sino-Japanese War in this exhibition, which he also exhibited at the annual American Artists’ Congress exhibition and the “An Exhibition of In Defense of World Democracy: Dedicated to the Peoples of Spain and China”.

Catalogue, Museum of Modern Art Wakayama

Ch. 6, Fig. 116

Eitaro Ishigaki, Flight, c.1937

Eitaro Ishigaki exhibited this work in an exhibition organized by the American Artists’ Congress, “In Defense of World Democracy: An Exhibition Dedicated to the Peoples of Spain and China,” as well as the New York Civic Art Exhibition.

Catalogue, Museum of Modern Art Wakayama

Ch. 6, Fig. 117

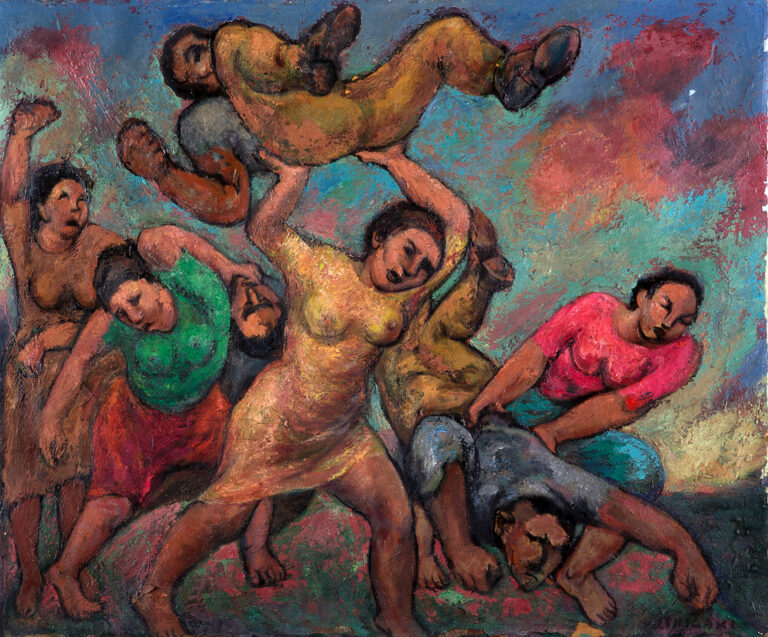

Eitaro Ishigaki, Amazons, 1937

In March 1939, the fascist regime triumphed in Spain after a civil war that had been raging since 1936. This work depicts people protesting against the fascist regime. It represents a Spanish woman attempting to throw a Fascist soldier off a cliff. Fig. 117. is an illustration from the catalog of the American Artists’ Congress, while Fig. 118 is a work of the same composition and the same title, now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama. In Fig. 117, the soldier has a gun in his hand and the soldier on the right is wearing a helmet, but in Fig 118, they have been removed. Fig. 118 seems like it was modified by the artist later.

Image Source:

Ch. 6, Fig. 118

Eitaro Ishigaki, Amazons (revised version), c. 1937

Image Source:

Ch. 6, Fig. 119

Chuzo Tamotzu, Where the Cherry Trees Bloom, c.1938-1939

A cherry tree in full bloom, a large sword in the center, a tank on the far left, and a human face in the foreground symbolically represent the horrors of war.

Catalogue of the American Artists' Congress, 1939

Ch. 6, Fig. 120

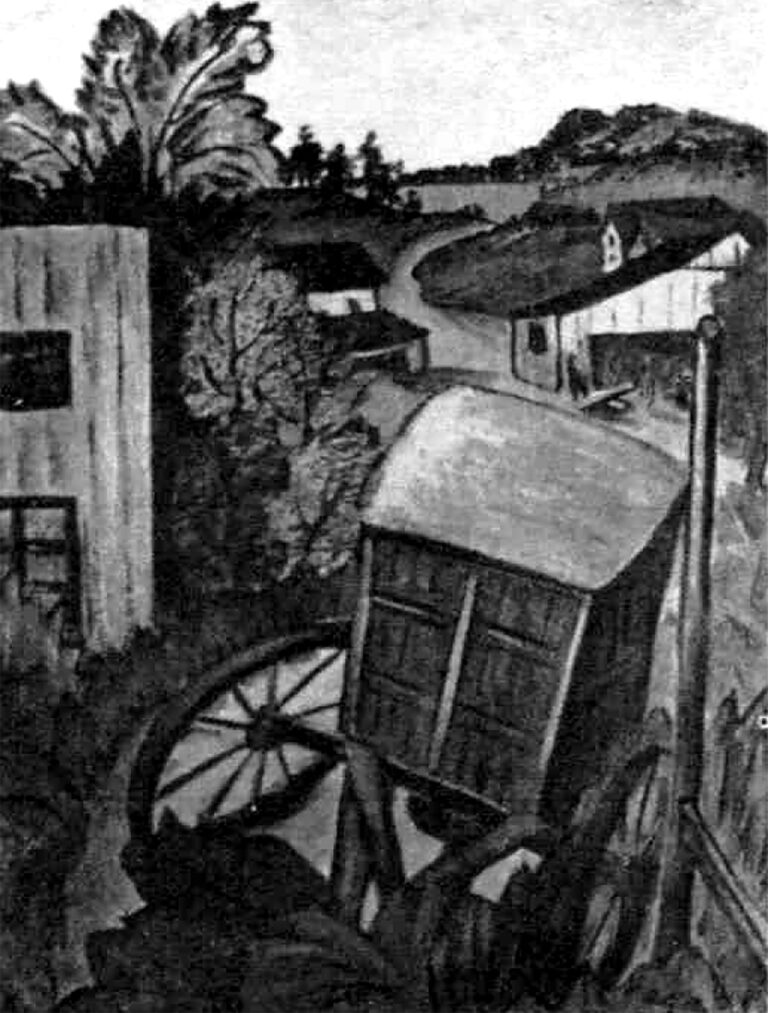

Thomas Nagai, Broken Wagon, c.1938-1939

This painting depicts a broken wagon with its wheels off, placed on the side of a suburban road. This landscape painting uses thick lines to create a clear outline of the objects.

Catalogue of the American Artists' Congress, 1939

Ch. 6, Fig. 121

Sakari Suzuki, Hand of Justice, c.1938-1939

This surrealist painting depicts a giant hand carrying a cross grasping the rubble from war.

Catalogue of the American Artists' Congress, 1939

Ch. 6, Fig. 122

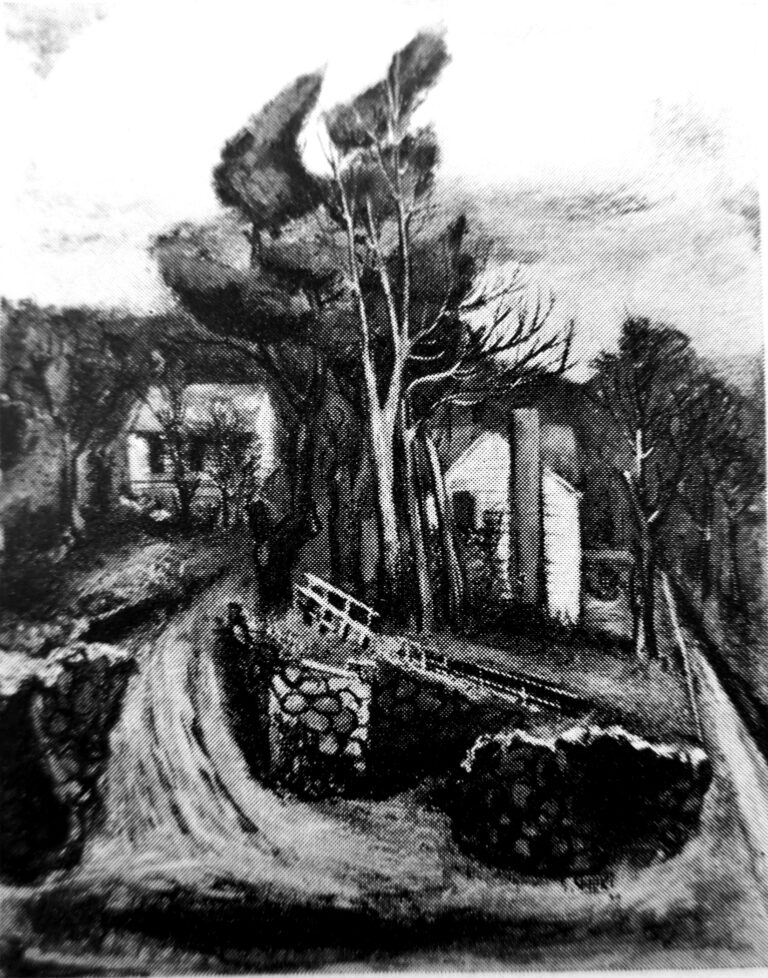

Sakari Suzuki, Landscape, c. 1939-1940

A large tree standing on a stone wall and a house in the woods, perhaps in the suburbs of New York. This landscape is slightly different from the war-themed works in the exhibition. “Maverick Street,” similar in composition to this work, is in the Smithsonian American Art Museum collection.

Catalogue of the American Artists' Congress, 1940

Ch. 6, Fig. 123

Chuzo Tamotzu, Problem, c.1939-1940

A furry animal with a long tail sits on a table by the window. Outside the window are the buildings of New York City and automobiles driving down the street. The animal appears to be in an indoor setting. Upon closer inspection, one can see that the bundle of paper placed randomly under the animal’s feet shows a sword and gun, symbolizing battle, and the other paper shows a sickle and hammer, symbols of labor and unity, also used in the Communist mark. Just before the opening of this exhibition, in December 1939, the Soviets invaded Finland and the Second World War began. Thus, this work could be considered a protest against the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe.

Catalogue of the American Artists' Congress, 1940

Ch. 7, Fig. 124

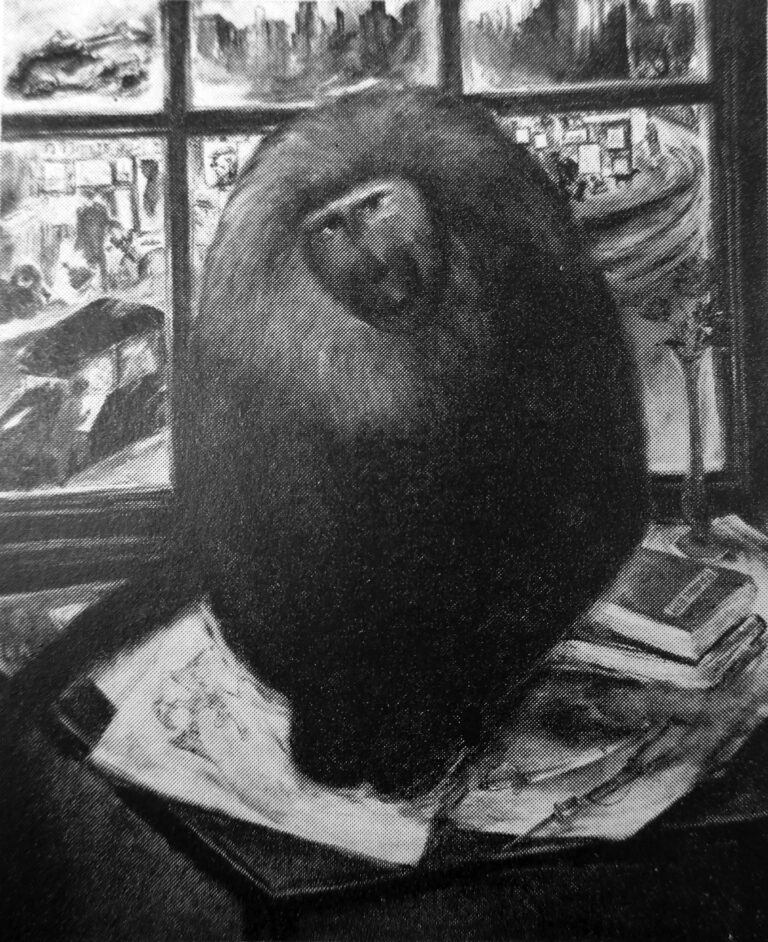

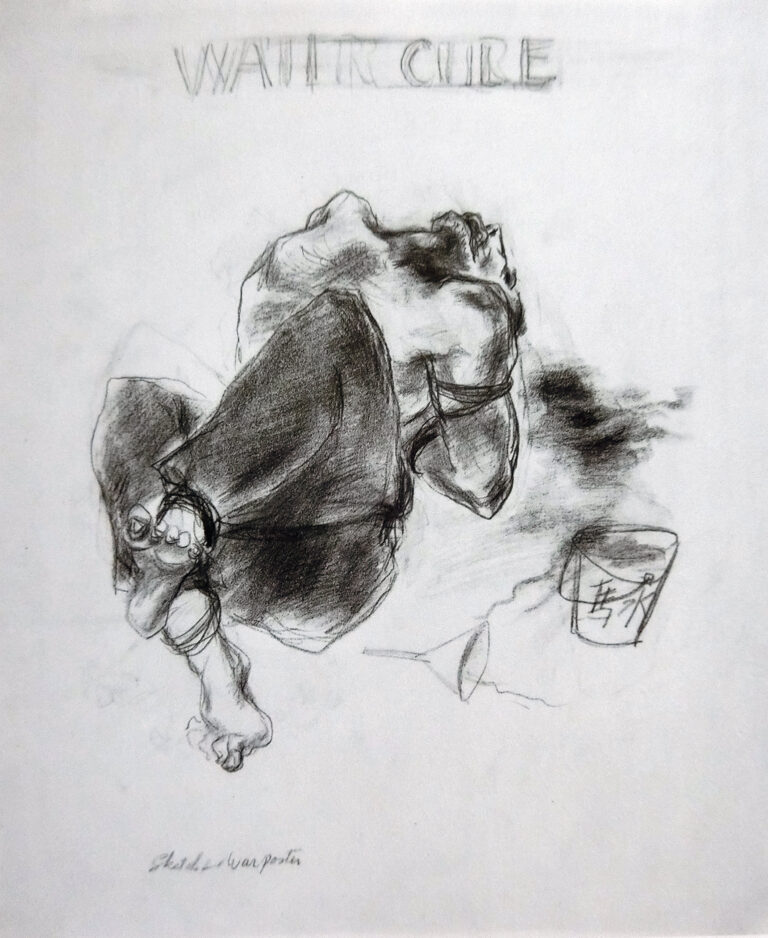

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Water Cure, 1943

Fukutake Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 125

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Kiler, 1943

Fukutake Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 126

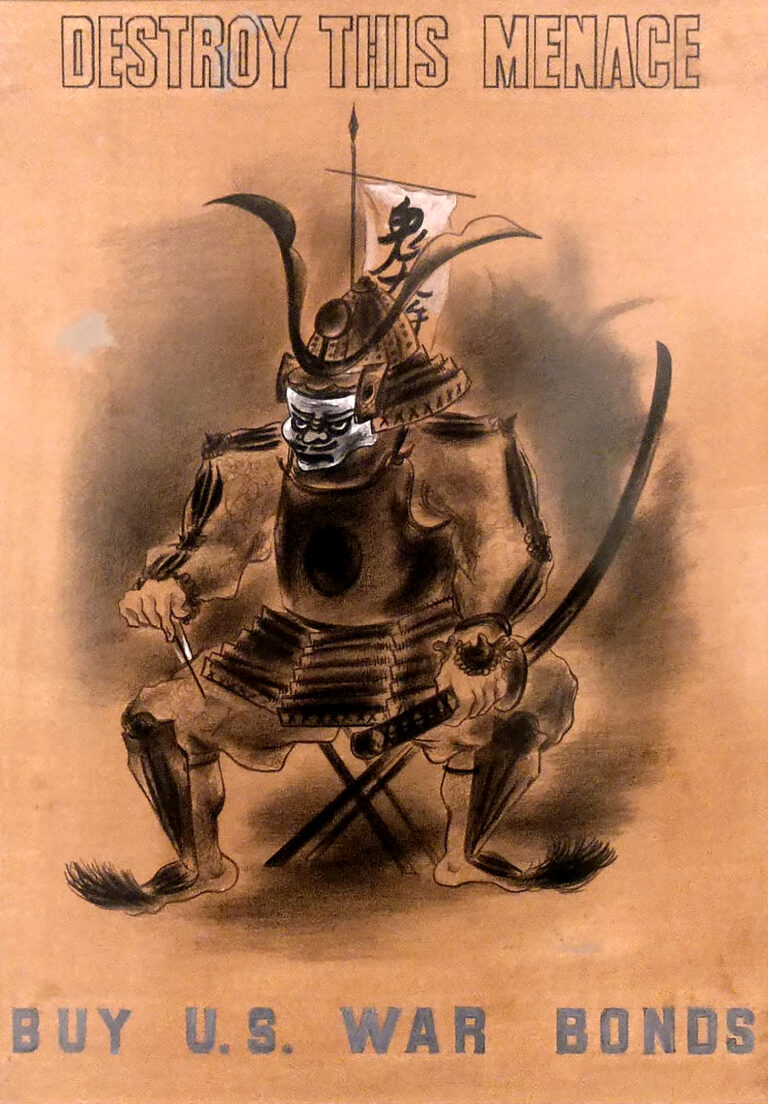

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Destroy this Menace, Buy U.S. War Bonds, 1943

Fukutake Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 127

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Clean Up This Mess, 1942

Fukutake Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 128

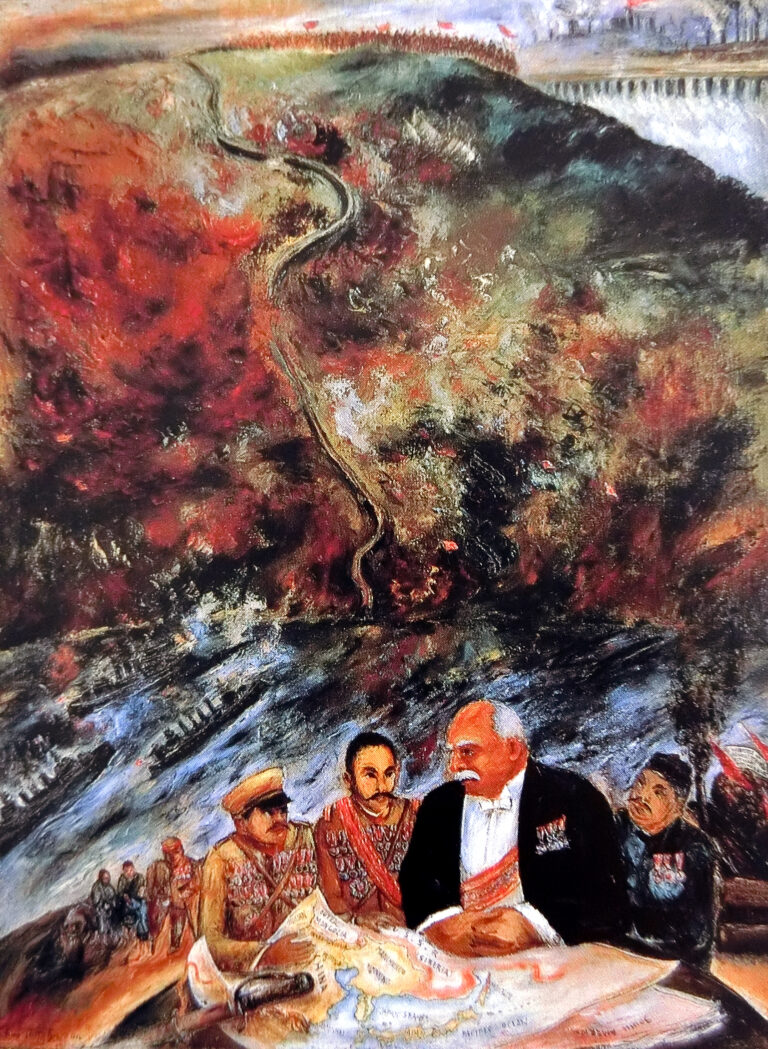

Chuzo Tamotzu, Teared Map of China, 1933

Private Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 129

Chuzo Tamotzu, Victim of Militarism, 1940

Private Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 130

Chuzo Tamotzu, Tanks and Soliders, 1944

Private Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 131

Chuzo Tamotzu, Dilemma, 1941

Private Collection

Ch. 7, Fig. 132

Toshi Shimizu, Charge, 1943

Image Source:

Ch. 7, Fig. 133

Toshi Shimizu, Machine Guns, 1943

Image Source: