Calls for Change

In 1872, the Japanese government issued the “Gakusei” order requiring all children in the country to receive a primary education. Secondary schools followed shortly thereafter and Japan’s university system gradually became more robust. However, these developments were not enjoyed equally by male and female students.

In the beginning, female attendance at primary school lagged far behind male attendance and for many decades after the edict, the schools themselves were generally gender-segregated. Furthermore, secondary schools for girls usually served limited purposes and only prepared them for careers in teaching (at the primary school level), domestic work, or the arts. And finally, at the university level, there was virtually no opportunity for women to participate in meaningful numbers until the turn of the twentieth century.

Throughout this time, Quaker missionaries and teachers, along with some of the first native Japanese Quakers, began to establish their own schools and to advocate for expanded opportunities for young girls and women alike.

Many of these individuals had prominent ties to the New York community and were instrumental in setting the stage for post-WWII reforms that would finally remedy some of the limitations placed on women’s education.

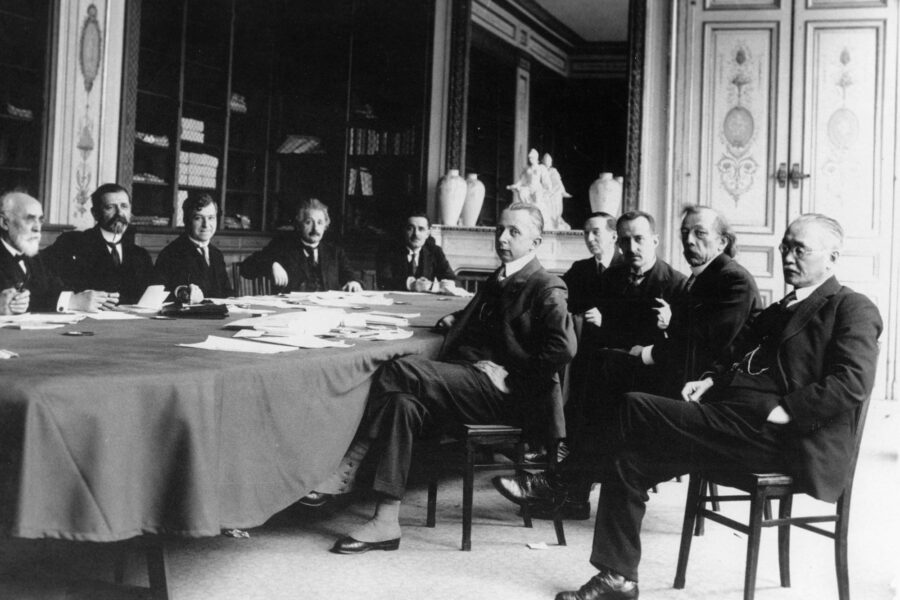

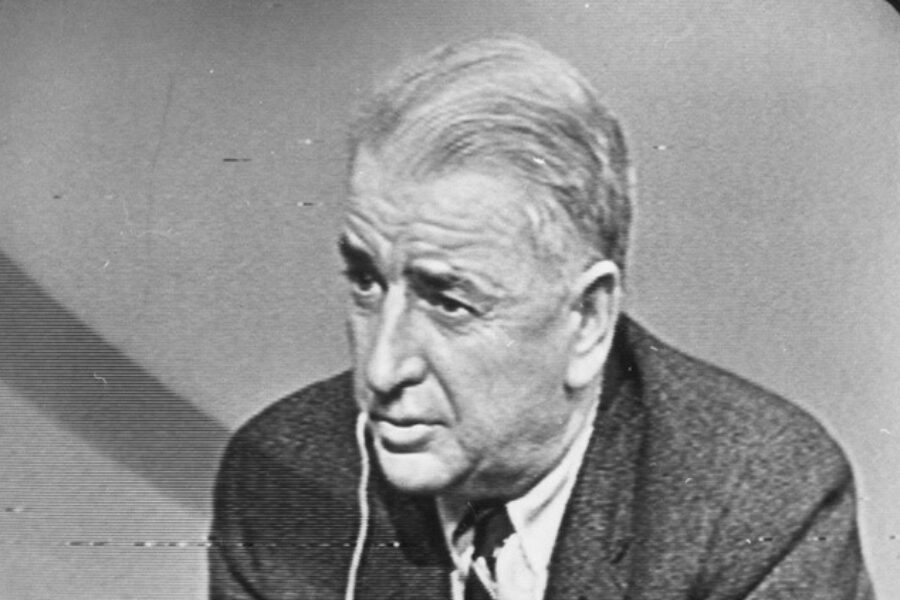

Inazo Nitobe

Possibly the most famous Japanese Quaker, Inazo Nitobe was an intellectual and public figure who came to be widely known in the Western world for his writings on both Japanese culture and the international world order. Nitobe has a checkered legacy, as his various roles like university professor and Under-Secretary General for the United Nations were interspersed with others such as colonial administrator in Taiwan. However, one of his most significant historical contributions was his long term advocacy for the expansion of access to higher education for women in Japan and around the world. Nitobe used his connections and prominence to help a number of Japanese women attain educations in the United States and elsewhere when opportunities were scarce in their home country, and he spoke on the importance of women’s education to international audiences in New York and across the globe.

“I very much like their simplicity and earnestness,” were Nitobe’s words when asked why he had begun to attend Quaker meetings as a young man studying abroad in the United States. He joined the Religious Society of Friends in 1885, remained a member throughout his life, and even met his wife, Mary Elkinton through the Friends community in Philadelphia. In addition to Mary, the rest of the Elkinton family became lasting supporters of Japan and especially the many Japanese students that passed through Quaker networks from the late 19th century on.

Nitobe and Mary facilitated the study of many female Japanese students in the U.S., including prominent figures such as Michi Kawai and Ai Hoshino, both of whom received scholarships from the Quaker community. Nitobe also advised the establishment of the Friends Girls School in Tokyo in 1887 (the first dedicated Quaker school for girls in Japan), supported Umeko Tsuda in her efforts to build Tsuda College (which was endowed largely with Quaker funds), and later helped to found the Tokyo Woman’s Christian University, serving as its first president.

Despite these accomplishments, Nitobe was still critical of the lack of opportunities for women’s education in his home country during this time. In 1911, New York provided him the opportunity to make one of his clearest indictments yet when he was named one of the inaugural exchange professors of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. In this role, he gave a series of lectures at Columbia University, during one of which he stated:

“A curious fact, hard to account for in so progressive a Government as [Japan’s], is the chronic reluctance it has toward the higher education of women…At present, there are private institutions of excellent reputation–the so-called “Women’s University” under Mr. Naruse [‘so-called’ because the government had not yet granted it official university status], Miss Tsuda’s English School, two or three well-equipped seminaries under missionary management–doing work such as the Government has failed to make possible by its own initiative and on its own responsibility.”

It is easy to see why he felt compelled to directly support efforts to address the problem himself, and why his faith played a central role in shaping those efforts, as nearly all of the institutions he mentioned received substantial support from Christian organizations abroad. The Japan Society of New York later published the full series of Nitobe’s lectures, thereby preserving his advocacy for this cause among international audiences.

Unfortunately, Nitobe did not live to see a number of significant reforms that came to the Japanese education system after World War II, including the entry of women into standard universities and the recognition of existing women’s institutes as state-approved universities. But he contributed to the movement in the ways he was able to within his own time. His Quaker faith and the platform he found in New York and around the globe allowed him to lay a groundwork for others in Japan and the U.S. to follow. And indeed many of those who chose to pick up this mantle came from the same Quaker roots, one of whom was Hugh Borton.

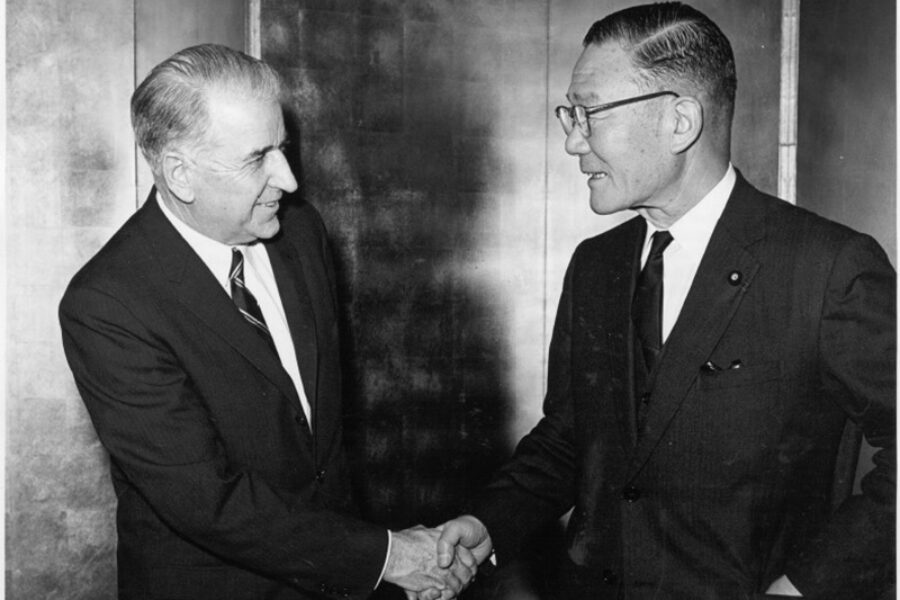

Hugh Borton

Did you know?

As a U.S. State Department official, Borton worked on several memoranda proposing changes to the Japanese education system prior to Japan’s surrender in 1945. At the time, U.S. officials were concerned with eliminating what they perceived as nationalistic trends in the schools, and much of Borton’s work focused on this issue. But he also noted other issues in Japanese society, such as the historical resistance to women’s movements.

“A feminist movement, including sponsorship of foreign education for a select group of young women, the first of whom were chaperoned as far as the United States by the Iwakura Mission in 1871, had little effect on the inferior position of women in Japanese society. The [1889] Constitution and the new [sic] codes verified this unequal status.”

Of the school system itself, he noted the shortcomings of earlier efforts such as the 1872 Education Law:

““The system, as it was laid down on paper, was magnificent. It provided that boys and girls of all classes should receive primary education and that the more gifted should be given advanced training…But in reality, much had to be done to implement this new code…Actually, as late as 1890 only half of those eligible for a primary education were taken care of.”

This was even more true for girls than for boys, and so when Borton recommended increasing educational opportunities for women, he joined Nitobe as one of the most prominent Quaker intellectuals calling for the advancement of equal rights for women in Japan.

Unlike Nitobe, however, Borton was fortunate enough to see his recommendations come to fruition during his lifetime. By the time women’s improved access to primary school and higher education was codified into law in the late 1940s, Borton was primarily working on other issues but several of his closest friends and colleagues, including fellow Quaker and Japan expert Gordon Bowles and Shigeru Nanbara, the president of Tokyo Imperial University, had been directly inspired by him and were involved in the final approval of these measures.

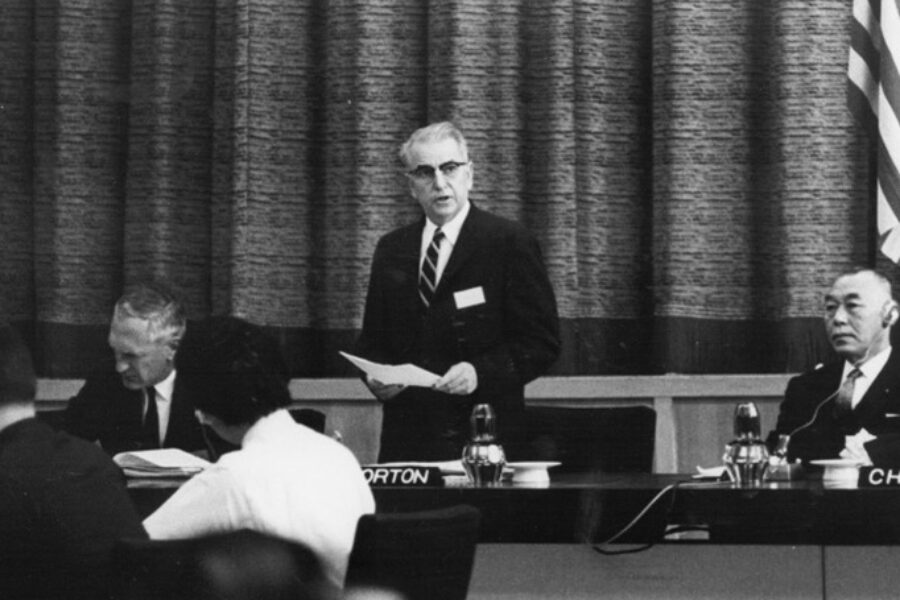

President Kennedy and CULCON delegates 10-18-63; Borton is center, to Kennedy’s right, with back towards camera