Spirit and Sacrifice Beyond the Diamond:

150 Years of Japanese Baseball

About The Exhibit

In 2022, Japan celebrated baseball’s sesquicentennial – the 150th birthday of a national pastime and obsession in the Land of the Rising Sun. What started as a school sport in Tokyo has forged a path for many Japanese players to make it to the Major Leagues, with names such as Ichiro, Matsui, Darvish, Tanaka, Ohtani, and Yoshida peppering the rosters in America’s largest stadiums.

Yet, there is more to the story of Japanese baseball than bright lights and the fame of legendary players. In a game tied historically and symbolically to the American dream – both the promise of prosperity and the aspiration of social mobility through individual success – there are deeper roots. Crushing failures, closed doors, and America’s deeply-rooted racism punctuate the story.

Presented and curated by the Digital Museum of the History of Japanese in New York, this exhibit introduces how the first generations of nikkei (ethnic Japanese residing outside of Japan) and Japanese pioneers in Major League Baseball have overcome racial and ethnic stereotyping. They count every run-batted-in, base-gained, grueling victory and cruising defeat as a step towards equality. For nikkei, including Japanese New Yorkers, baseball has served to reinforce their cultural assimilation and pride in their Japanese heritage. The cultural shifts on the diamond often reflect the shifting definitions of Japanese American identity.

August 21, 2009, during the heated sixth game of the World Series, Hideki Matsui of the New York Yankees hit his third home run of the Series against the Philadelphia Phillies. It was a run that became an iconic moment in Major League Baseball (MLB) history, securing Matsui the title of Most Valuable Player in the World Series and making him the first Japanese-born player and full-time designated hitter to ever win the award. The moment felt like proof of Matsui’s belief that ethnic Japanese power hitters can compete at the same level as the best American and Latin American sluggers. Matsui was now alongside legends like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. After seven years with the Yankees and a nine-year contract in the league, Matsui had left his mark on the most renowned team in baseball.

Courtesy of MLB.com.

Courtesy of the Nisei Research Baseball Project.

ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT IN JAPAN

1872-1896

Horace Wilson, an American educator and foreign advisor for the modernization of the Japanese education system following the Meiji Restoration, decided that his students needed more physical exercise. In 1872, he introduced them to “base ball”. The new game garnered interest and excited young players. Six years later, Hiroshi Hiraoka organized the Shinbashi Athletic Club, the first formal all-Japanese baseball team in the country. In 1896 the first documentation of a Japanese baseball team defeating an American baseball team was recorded in Tokyo; the Ichikō High School team won three out of four games against the Yokohama Country Athletic Club and the US Navy cruiser USS Detroit, both teams which included mostly American players.

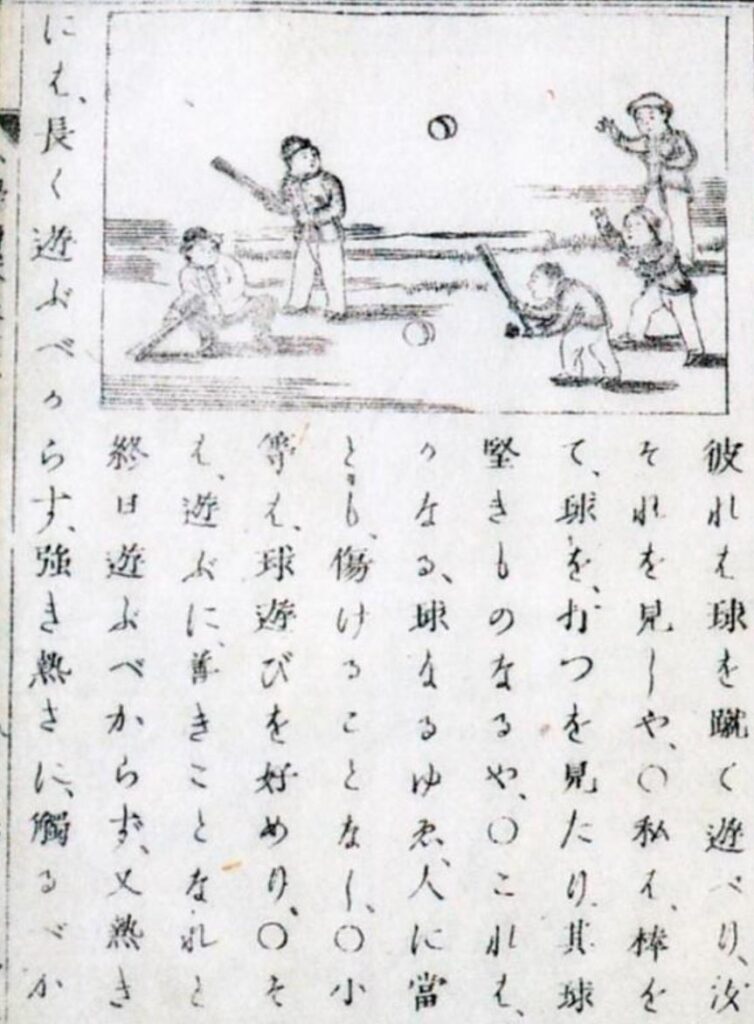

EARLY DEPICTION OF BASEBALL

A page from an 1873 Japanese school textbook, “Elementary Reader” (⼩ 学読本), depicts an early form of baseball in Japan with an illustration titled “playing with a ball.”

Courtesy of Japan Archives.

Courtesy of the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

A photograph of Hiroshi Hiraoka, seen in the center of the middle row, with his teammates at the Shimbashi Athletic Club in 1878. Hiroshi Hiraoka (1856–1934) is known as the father of Japanese baseball. While Wilson introduced the game, Hiraoka spread the passion. His interest began in 1871 when Hiraoka traveled to Boston and Philadelphia to study railroad technology. While in Boston, he met Albert G. Spalding (1849–1915), a pitcher for the Boston Red Stockings and future co-founder of the National League (NL), the first “major league” which began in 1876. Hiraoka also visited New York City, where he spent hours observing urban baseball, colloquially known as stickball, which was played throughout the city streets. After five years in America, Hiraoka returned to Japan as a devout baseball fan. He set out to create his own team, referencing guidebooks and equipment collected during his East Coast travels. In 1878 the Shinbashi Athletic Club was formed, the first official all-Japanese baseball team.

A scan of The Japan Weekly Mail newspaper recounting the details of a baseball game between the Ichikō High School team and the USS Detroit team in June 1896. In 1896 in Tokyo, the all-Japanese Ichikō High School baseball team defeated teams with a majority of American players in three consecutive games. The first win against the Yokohama Country and Athletic Club (YCAC) was such a landslide, 29-4, that it prompted calls for a rematch. For the second game American Navy sailors from the USS Detroit cruiser joined the YCAC team, only to lose again, 9-28. Word of the second crushing defeat spread quickly. To quell the embarrassment, the USS Detroit sailors challenged the Ichikō students for a third time. Once again, the Americans were sorely defeated, 6-22. In a final game, played to much anticipation on July 4, 1896, the Americans got their victory, winning narrowly 14-12. The results of the games were published in local and foreign newspapers, as evidenced by this June 13, 1896 article from The Japan Weekly Mail. With three out of four wins under their belts, the Ichikō High School team and their head coach became national celebrities, skyrocketing baseball’s popularity in Japan.

Courtesy of Japan Archives.

Courtesy UHM Library Digital Image Collections.

NiSEI BASEBALL LEAGUE IN HAWAI'I (1908) and barnstorming team visits new York (1913)

1872-1896

Japan’s national love for baseball radiated internationally and spread to diasporic communities in Hawai’i. At the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, Hawaii’s sugar plantations were thriving and became a lucrative job market for Japanese workers across the Pacific. Unlike other immigrants to the islands, the Japanese workers were already familiar with baseball. They shared their passion for the sport with the island’s working-class ethnic communities.

1) Courtesy of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

2) Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

THE HAWAIIAN TRAVELERS

This first photo was taken on October 24, 1916. The Hawaiian Travelers, a multi-ethnic, barnstorming baseball team from Hawaii, toured the American mainland between 1912 and 1916, playing in 132 exhibition games. The team was also known as the “Chinese Travelers.” In 1913, the Travelers played games in the tristate region against teams that included the New York Lincoln Giants, a Negro League team, and the Seton Hall Pirates, a college team. Among the team members were three nisei, James Chinito (“Jimmy”) Moriyama (1893-1950), his brother Clement .(‘Clem”) Moriyama (1894- 1970), and Andy Masayoshi ‘Yamashiro (1896-1941). To align himself with the team’s alternate name, ‘Yamashiro adopted the pseudonym “Andy Yim.” The Travelers demonstrated to American audiences the ability of Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians to play competitive baseball against white and black Americans.

The second photo is of Andy Yamashiro playing football for Temple Preparatory School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 22, 1916. In 1916, when the Hawaiian Travelers completed their national tour, Andy Yamashiro, still known as “Andy Yim,” returned to Philadelphia and enrolled at Temple Preparatory School. During his studies, Yamashiro became a right guardsman on the school’s football team, memorialized in this photo from November 22, 1916. His athletic pursuits paid off, and he went on to play professional baseball for a minor league team in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Yamashiro is among the first Asian Americans to play professional baseball.

GOLDEN ERA OF NISEI BASEBALL

1920-1941

At the start of the 20th century the popularity of baseball spread throughout Japanese American communities. Nisei leagues were formed across the country and grew in numbers beginning in the 1910s. The passion for baseball among second-generation Japanese Americans led many baseball historians to coin the 1920s and 1930s the “Golden Era of Nisei Baseball.” Most nisei teams were concentrated on the Pacific Coast, but some, such as the Nippon Athletic Club, existed in New York City as early as 1916. However, it was only post-World War II that New York would gain a Japanese American baseball league. During this time the Chinese American Buck Lai stood as the only player of Asian origin in a MLB club.

In 1931 an American all-star team toured Japan, playing in exhibition games with Japanese teams. The tour drew crowds, but three years later, in 1934, the popularity of the game exploded when Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and other American baseball icons joined the American All-Stars. The presence of Ruth, who was regarded then and now as the greatest baseball player of all time, made the 1934 tour different than any other and rapidly increased baseball’s fanbase in Japan.

Courtesy of Japan Archives.

Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. ID: B-277-51-21.

Photograph of Princess Toshiko, Prince Tsunenori Kaya, and Babe Ruth during royal visit to New York’s Yankee Stadium. August 15, 1934.

1934 AMERICAN LEAGUE ALL-STAR TOUR OF JAPAN

A group photo of the all-American and all-Nippon baseball teams at Meiji Jingu Stadium in Tokyo during the first game of the American League all-star tour of Japan on November 3, 1934. On November 3, 1934, fans packed the Meiji Jingu Stadium in Tokyo for the first game of the American League All-Star tour of Japan. The American team, stacked with some of the best players of all time, won the first game 17-1. Their streak continued, and they won the following 15 games as well. While victory for the Americans was abundant, the tour was not without memorable moments.

On November 20, 1934, at Kusanagi Stadium Eiji Sawamura, a 17-year-old, high school phenomenon, was pitching for the all-Nippon team. He was zoned in, pitching the entirety of the game and limiting the hard-hitting American team to one run on five hits. During one stretch, he struck out Gehringer, Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx in consecutive order. Although the all-Nippon team lost the game, 1-0, Connie Mack, the manager of the All-American team, was impressed. He found Sawamura after the game and offered him a contract with the Philadelphia Athletics, the team he both managed and owned. Sawamura politely declined.

BUCK LAI

William Tin (“Buck”) Lai (1894–1976) practices with the New York Giants in 1928. In 1928, the New York Giants, at the recommendation of their manager John McGraw, signed William Tin (“Buck”) Lai to the team, making him the first Asian American player to compete in the major leagues. Lai, a 33-year-old Chinese American, was a longtime minor league player, and semi-pro third basemen, with enough skill to compete alongside the greats. Despite his Hawaiian birth and American citizenship, the New York print media called attention only to Lai’s Asian ancestry. Ahead of his first game with the Giants, The Republican-Journal quipped, “Pity the poor baseball statisticians who have to translate the weekly batting averages into Chinese characters.” The discrimination overpowered Lai’s talent; the Giants sold his contract to a minor league team in Jersey City after only two games, neither of which Lai played.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

All Hawaiian Nine

This is an undated publicity photo of the All Hawaiian Nine. Buck Lai is third from the left in the photo. In 1928 Buck Lai, in the disappointing wake of losing his contract with the New York Giants, crossed the Hudson to play four games with the Jersey City Skeeters of the International League. He then rejoined the Brooklyn Bushwicks, the semi-pro team he had played on before signing with the Giants. Seven years later, in 1935, Lai left New York to return to his native Hawai’i. He soon formed a barnstorming team named the “All Hawaiian Nine,” a team composed predominantly of players of Chinese or Japanese ancestry.

The All Hawaiian Nine played exhibition games across the United States and brought Lai back to New York City to compete against the Brooklyn Bushwicks, Pennsylvania Red Caps, and Central Park Pine Grovers. World War II brought their tour to a stop, and post-war Lai returned to Brooklyn to work as a scout and instructor for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He later served as the baseball and basketball coach for the Long Island University (LIU) Brooklyn Blackbirds, and the athletic director and Provost at LIU Brooklyn.

TRYING TIMES

1941-1946

In December 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the entry of the United States into World War II, the foundations of Japanese American life began to shake. As the United States descended into racial hysteria, American political leaders and the media raised unfounded concerns of espionage and sabotage by nikkei. Two months after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forcible removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry – two-thirds of whom were American citizens – from their homes on the Pacific coast. They were taken to makeshift assembly centers (converted horse racing tracks and fairgrounds), and then to concentration camps, euphemistically named “War Relocation Centers,” situated in deserts or swamps. The ten isolated camps housed more than 120,000 Japanese Americans. For all of the nikkei, the transition was unjustly abrupt and devastating. A few communities were given a mere 48 hours to sell their valuables, homes, and businesses, while the remainder had only a few months to uproot their lives. In the camps, daily oppression and heavy surveillance were heavy reminders to Japanese Americans that they were outsiders in their own country.

“Japanese American baseball served a meaningful socioeconomic role and entertainment lifestyle for this closely knit ethnic group on the wrong side of the tracks.”

Branch Rickey (center) with LA Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley

(left) and former Chicago Cubs pitcher Bob Carpenter (right).

December 10, 1951.

Seemingly overnight, life for Japanese Americans turned horrifically upside down. For many incarcerated families, baseball served as a source of comfort from their past life and brought a semblance of their former freedom. Many Japanese Americans turned to the sport as a way to overcome the drudgery of daily life in the camps. Fred Oshima, a sportswriter for the Rohwer Outpost – a newspaper published at the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas where he was incarcerated – recalls, “Japanese American baseball served a meaningful socioeconomic role and entertainment lifestyle for this closely knit ethnic group on the wrong side of the tracks.”

On the East Coast a lesser number of Japanese Americans were incarcerated, ironically on Ellis Island, and most avoided forcible removal or arrest. However, the general atmosphere of distrust and racism towards Asian Americans after the outbreak of World War II led many issei and nisei to lose their jobs. Some were placed under government surveillance, others were subjected to warrantless searches of their homes, and all non-citizen issei had to register as “enemy aliens” and carry special identification cards. In 1994, New York City Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia verbalized unfounded discrimination, expressing that Japanese Americans resettled from camps in Manhattan and Brooklyn could pose “potential dangers” near New York’s military installations, plants, or shipping facilities.

Courtesy of Thomas Martin.

Between 1943 and 1945, the War Relocation Authority granted leave clearance for more than 4,000 graduating high school seniors to leave the concentration camps to attend institutions of higher learning in the Midwestern or Eastern United States. These institutions included the University of Connecticut. This photograph depicts the 1945 University of Connecticut baseball team. Two of the players, Hiyakawa (first row, far left) and Kiyokawa (first row, far right), were among the students who had received leave clearance.

POSTWAR PIONEERS

1941-1946

By 1946, Japanese Americans who had been housed in internment camps were resettled. Combined with nisei war veterans and students from Hawai’i, the city’s wartime nikkei community had more than doubled. Many of these newcomers were nisei in their 20s and 30s, the largest demographic of baseball enthusiasts. Around the city, they joined together to form all-nisei baseball and softball leagues.

1) Courtesy of Densho.

2) Courtesy of Thomas Martin.

the weekender league

The first image is a scan of the May 30, 1946 issue of The Nisei Weekender announces the creation of the “Weekender League”, an all-Japanese softball league in New York City. Less than three months after the final War Relocation Authority closed in Tule Lake, California in March 1946, the Weekender League was born. The league took its name after The Nisei Weekender, a New York newspaper for Japanese Americans. An issue of the newspaper published on May 30, 1946, describes the formation of the league, saying, “Excitement reached a fever pitch as the local baseball-conscious community eagerly watched the 11th-hour formation of seven well-matched softball teams.” The seven teams in the Weekender League were funded by Japanese American businesses and local religious organizations, and they competed for a silver trophy donated by the Hokubei Shimpo, the first New York newspaper to publish in Japanese after World War II. The second picture is of an unknown player for the New York L’il Giants, a Japanese American amateur team, practicing at Riverside Playground in Manhattan in 1948.

The opening pitch for the league’s inaugural game was thrown by Dr. Masahiko “Ralph” Takami (1912-1967). Ralph was the son of Dr. Toyohiko Campbell Takami (1872-1945), a New York issei who founded the Japanese Mutual Aid Association in 1907 (renamed the Japanese Association in 1914, and now the Japanese American Association of New York). Growing up in an affluent circle of city-goers, Ralph and his brother Morihiko “Mori” (1915 -1993) were schoolmates with the Topping brothers, Daniel R. “Dan” Topping and Henry J. “Bob” Topping Jr at the Lawrenceville School. Baseball ran serendipitously through Ralph’s social circle; Dan Topping served as co-owner of the Yankees between 1945-1964 and President between 1948-1966.

The New York Japanese baseball community grew strong grassroots but had to look beyond the tri-state region to find sources of representation and inspiration in the major leagues...

WALLY YONAMINE

Wally Yonamine (1925–2011), born in Maui, Hawai’i, was a nisei of Okinawa and Japanese ancestry and the first ethnic Japanese to play professional American football. In 1947, he was a running back for the San Francisco 49ers, but an off-season injury led to his dismissal in 1948. Yonamine did something radical – he changed sports. In 1950, he began playing minor league baseball for the Salt Lake City Bees. That autumn, Yonamine had dinner with two men who changed the course of his career: Joe DiMaggio, the Yankees’ star outfielder, and Lefty O’Doul, a two-time NL (National League) batting champion and the manager of the minor league San Francisco Seals. Both were knowledgeable about baseball in Japan, O’Doul even helped to popularize baseball in Japan during the 1930s. He arranged for Yonamine to sign with the Yomiuri Giants, a team in the Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB) league. Yonamine moved to Japan and enjoyed a 12-year career as an outfielder and first baseman. He brought his American idiosyncrasies to the Japanese game, and today is credited with introducing aggressive tactics such as sliding with spikes up toward infielders’ legs and diving for fly balls. His tenacity won the Central League’s MVP award in 1957 and finished his career with a .311 lifetime batting average.

Wally Yonamine on the Yomiura Giants in the mid-1950s. Courtesy of Paul Yonamine.

1960s PIONEERS

In 1964, Masanori Murakami became the first Japanese player in MLB when he signed with the San Francisco Giants. He endured the major leagues only slightly longer than William Tin (“Buck”) Lai. After a mere two seasons with the Giants, the Japanese baseball commissioner required Murakami to return to his Japanese team, the Nankai Hawks.

In 1967, Mike Lum became the first Japanese American in MLB, followed by Ryan Kurosaki in 1975 and Lenn Sakata in 1977. As the first nikkei in the league, Lum endured. He had a 15-year MLB career as an outfielder and first baseman, but consistently had difficulty obtaining a starting position on the Atlanta Braves and Cincinnati Reds. For Kurosaki, his time in the major leagues came too soon; he was given a brief opportunity to play with the St. Louis Cardinals before he was ready. Sakata had a successful 11 years in the MLB as a utility player and later realized his skills as a team manager. No major league team offered him an opportunity, despite his qualifications, so Sakata managed minor league teams for the rest of his career.

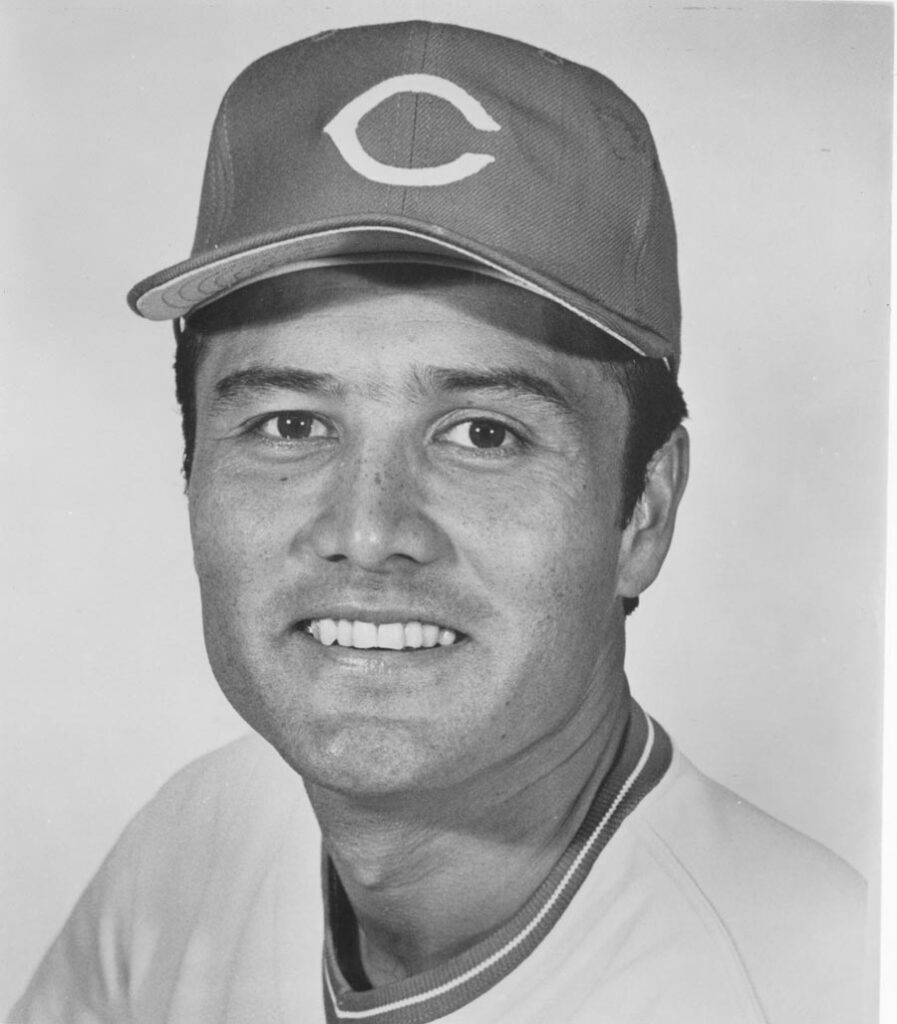

MIKE LUM

Official Cincinnati Reds MLB headshot for Mike Lum, 1976. Michael Ken-Wai (“Mike”) Lum (b. 1945) became the first Japanese American to play in MLB when he debuted with the Atlanta Braves in 1967. Lum was born in Honolulu, Hawai’i to a nisei mother and white American soldier father. He was raised and adopted by a Chinese American couple, Mun Luke and Winnifred Lum. It is unlikely that most New York Japanese knew about Lum’s Japanese ethnicity as the American press rarely mentioned his Japanese heritage – even after the adoption was revealed by the Associated Press on July 4, 1970.

An outfielder, Lum had difficulty breaking into the Braves’ starting lineup due to presence of Henry Aaron, Ralph Garr, and Dusty Baker. However, he received more playing time, beginning in 1971, when he was utilized at first base, as well as in the outfield. Lum had his best season in 1973, batting .294 with 16 home runs and 82 runs batted in 568 at-bats. After the 1975 season, the Braves traded Lum to the Cincinnati

Reds where he encountered a similar clogged outfield situation, and at first base. Lum had now become a bench player. Reds manager Sparky Anderson called Lum “the most underrated player in the National League.”

RYAN KUROSAKI

Ryan Yoshimoto Kurosaki (b. 1952) poses for an official team photograph with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1973. Born in Honolulu, Hawai’i, Ryan is a sansei (third-generation Japanese American). His parents, Katsuto Kurosaki and Toshiko (“Eleanor”) Fujii Kurosaki, were nisei. The Cardinals called up Kurosaki to the big club soon after the start of his second season in the minors. The St. Louis press was quick to point out Kurosaki’s Japanese ancestry and used it to signify his “otherness” and connections to a former World War II enemy. Before Kurosaki’s first game, an article in the St. Louis Post Dispatch stated, “Forget it, Ancient order of Hibernians [the largest Irish Catholic organization in America]. His first name may be Ryan, but he’s all Japanese.”

After a poor pitching performance for the Cardinals, another article in the St. Louis Post Dispatch declared, “Ryan Kurosaki was bombed like Nagasaki.” Kurosaki pitched a total of 13 innings to a 7.62 ERA in seven games with the Cardinals, and then was sent back down to the Double-A Arkansas Travelers, never to return to the majors. Bill Valentine, the Traveler’s announcer and later the team’s general manager, described what happened to Kurosaki in the following terms: “Here was a kid who had pitched one year in A ball, a few weeks in Double-A, and they pulled him up to pitch relief in the big leagues. No way he could have been ready. Then they sent him back and forgot about him.”

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

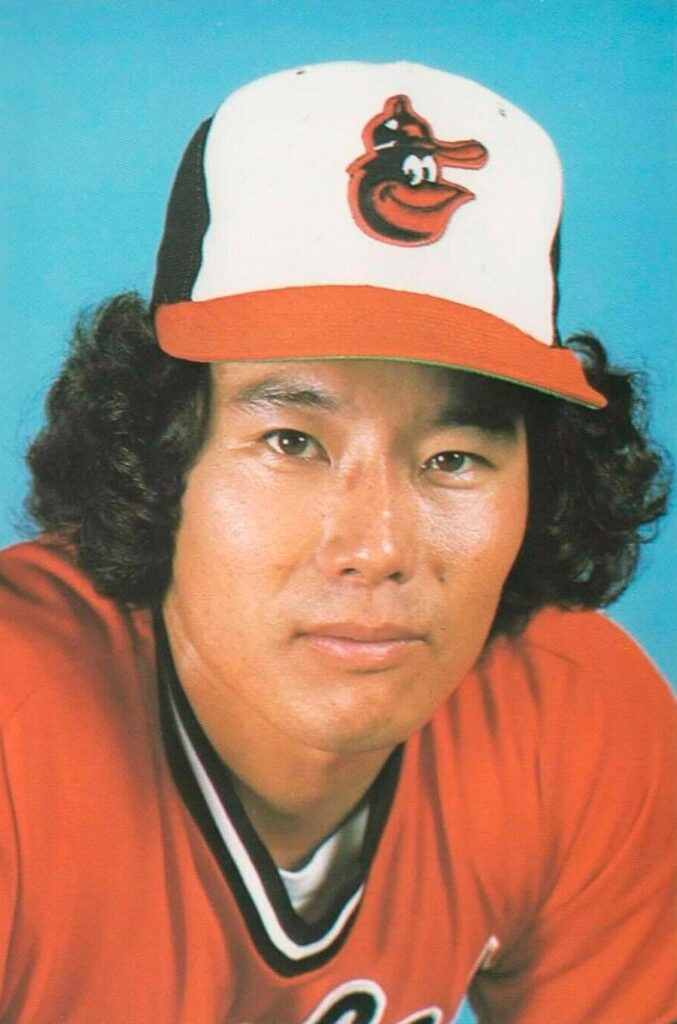

LENN SAKATA

Image of a cropped 1980 Baltimore Orioles baseball card of Lenn Sakata. By the 1980s Japanese players and nikkei of all generations still did not have significant representation in Major League Baseball. Murakami, the first Japanese player in MLB in 1964, paved the way for Japanese Americans Mike Lum and Ryan Kurosaki. Lenn Haruki Sakata (b. 1954), a high school teammate of Kurosaki, was next. Sakata, a yonsei (fourth-generation Japanese American) born in Honolulu, signed with the Milwaukee Brewers in 1977 after he graduated from Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. As a second baseman and shortstop, Sakata was primarily used as a utility player during his 11-year MLB career. While not a starting player, Sakata’s defensive prowess and reliability led him to the Baltimore Orioles, where he was part of the team that won the World Series in 1983. He was the first Asian and Asian American to be part of the highest victory in baseball. Sakata finished his major league career through the most famous gateway: the New York Yankees. He played two and a half months for the renowned team in 1987, his final season as a MLB player. Sakata went on to enjoy a lengthy career as a minor league manager.

PASSING THE TORCH

Thirty years after Masanori Murakami’s trailblazing season with the San Francisco Giants, Hideo Nomo arrived in California to play with the Los Angeles Dodgers. He was the second Japanese player to reach the major leagues, and many considered him a trailblazer in his own right. Tom Lasorda, the manager of the Dodgers when Nomo joined the team in 1995, described him as a player who “pioneered Japanese players’ transition to the United States.” He was known for his distinctive “tornado” style and was the only Japanese pitcher to throw a no-hitter game in the major leagues until 2015.

Nomo’s breakthrough career as a starting pitcher opened a door of opportunity. Soon, other Japanese pitchers followed in his footsteps. Hideki Irabu (1969–2011) debuted with the Yankees in 1997, Shigetoshi Hasegawa (b. 1968) started with the Anaheim Angels in 1997, Tomo Ohka (b. 1976) signed to the Boston Red Sox in 1999, and Kazuhiro Sasaki (b. 1968) had his MLB entrance with the Seattle Mariners in 2000. Nomo’s trailblazing continued into the 21st century, leading Japanese outfielders Ichiro Suzuki (b. 1973) to the Seattle Mariners in 2001, and Hideki Matsui (b. 1974) to the New York Yankees in 2002.

By the early 2000s Japanese nationals had carved a small space in MLB, but very few Japanese Americans had followed in the footsteps of Lum, Kurosaki, and Sakata. Pre 2005, the only nikkei to make it to the major leagues were Atlee Hammaker (b. 1958) a left-handed pitcher for the San Francisco Giants, Don Wakamatsu (b. 1963) who signed to the Chicago White Sox in 1991, Dave Roberts (b. 1972) who played with the Cleveland Indians in 1999, and Onan Masaoka (b. 1977) who pitched for the Los Angeles Dodgers starting in 1999.

From 2006 to the present day there have been approximately 24 nikkei players in the MLB, however, most of them have been part-time utility players. Two players stand as an exception: Shane Victorino and Kurt Suzuki, who became regular starters throughout their careers. Lum and Lenn Sakata, the original nikkei groundbreakers, have been vocal about the scarcity of Japanese American players, coaches, and managers in MLB, attributing the paucity to systemic racism.

In New York, nikkei players such as Kyle Higashioka of the Yankees and Japanese player Kodai Senga of the Mets continue the tradition of baseball filtered through Japanese culture. Their presence in the major league preserves the dream of making it big for Asian Americans who play amateur tournaments around all five boroughs, and beyond.

DEREK TATSUNO

This is a photograph of the Hawaiian Rainbow Warriors head coach Les Murakami (left) and Derek Tatsuno (right) in 1979. Hideo Nomo made it big, and other Japanese players such as Ichiro Suzuki and Hideki Matsui followed. Yet, after 1980 and before 2005 only a handful of nikkei utility players made it to MLB. In a 2021 interview with the Hawaii Herald, Lenn Sakata spoke candidly about the difficulties for Asian Americans in the league, saying, “There were a lot of instances where it wasn’t just blatant racism, but their attitudes about Asians were just condescending. . . . We were a bunch of second-class people sometimes; just invisible. The Asian stereotype at the time was that nobody was athletic, or even taken seriously. So I think that’s probably why nobody even attempted to try to come at it. It just didn’t seem like we fit in.”

Major League Baseball’s racist climate, combined with interest from Nippon Professional Baseball teams, led some talented nikkei players to avoid the league altogether. Derek Tatsuno (b. 1958) – the first 20-game winner and the all-time season leader in strikeouts in NCAA Division I college baseball – turned down contract offers from four MLB teams (including one team that drafted him in two different years) between 1976 and 1981. Instead, he pitched at the college level, and then for a team in Japan’s amateur league. Tatsuno’s objective wasn’t the fame and turbulence of MBL, it was stability. The NPB offered greater job security and a solid salary -and a way around the racial and professional stressors imposed by the major leagues. However, because MLB teams continued to draft him every year, Tatsuno was prohibited from signing a contract with a NPB team. Finally, in 1982, when the Milwaukee Brewers drafted Tatsuno, he signed. By 1988, Tatsuno had played six years for the Brewers’ AA affiliate and Single-A teams. He left baseball without ever playing a game in MLB.

Courtesy of The Star-Bulletin File.

MAUI BOYS

The first photograph is of Shane Victorino on the field with the Boston Red Sox in 2014, who he played with from 2012 to 2015. The second is a 2019 photograph of Kurt Suzuki playing for the Washington Nationals during a game at Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia. In 2006, after 25 years without a nikkei player starting in MLB, two Hawaiian men made a splash in the league. Both were Maui boys, born within three years of each other and raised only a few miles apart. They found their way to majors through different routes.

Shane Victorino (b. 1980), was drafted by the Dodgers straight out of high school in 1999. Born to parents of Portuguese, Native Hawaiian, and Okinawan descent, Victorino was a gifted athlete in soccer, basketball, football, and track, but fell in love with baseball. Victorino made his MLB debut in 2003 for the San Diego Padres, but didn’t become a regular starter until 2006 when he played centerfield for the Philadelphia Phillies. During his 12-year career in MLB, Victorino became known as “The Flyin’ Hawaiian,” a switch-hitter with a lifetime batting average of .275 on 4,630 at-bats, 231 stolen bases, and two-time leader of triples (a hit that advances the batter to third base) in the NL. In 2008, Victorino helped lead the Phillies to a World Series championship and was later a member of the 2013 World Series championship with the Red Sox.

Kurt Suzuki (b. 1983), a yonsei, was signed to the Oakland A’s in 2004 straight out of Cal State Fullerton, where he had won the Johnny Bench Award honoring the best collegiate catcher in America. The same year, Suzuki had also led the Fullerton Titans to the NCAA Division I Baseball Championship. Whereas Victorino was a high school star, Suzuki was the one to watch at a college level. Suzuki made his MLB debut in 2007 for the A’s and became a starting catcher in 2008. During his 16-year career, Suzuki batted .255 with 1,421 hits on 5,563 at-bats. In 2014, Suzuki made the MLB all-star team as a member of the Minnesota Twins and helped the Washington Nationals win the World Series in 2019.

ASIAN AMERICAN COACHES AND MANAGERS

Over the past 25 years, nikkei and Asian Americans have slowly but surely made their way into MLB. Curiously, this increase in representation has not corresponded to an increase in Asian American coaches and managers at the highest levels of the sport.

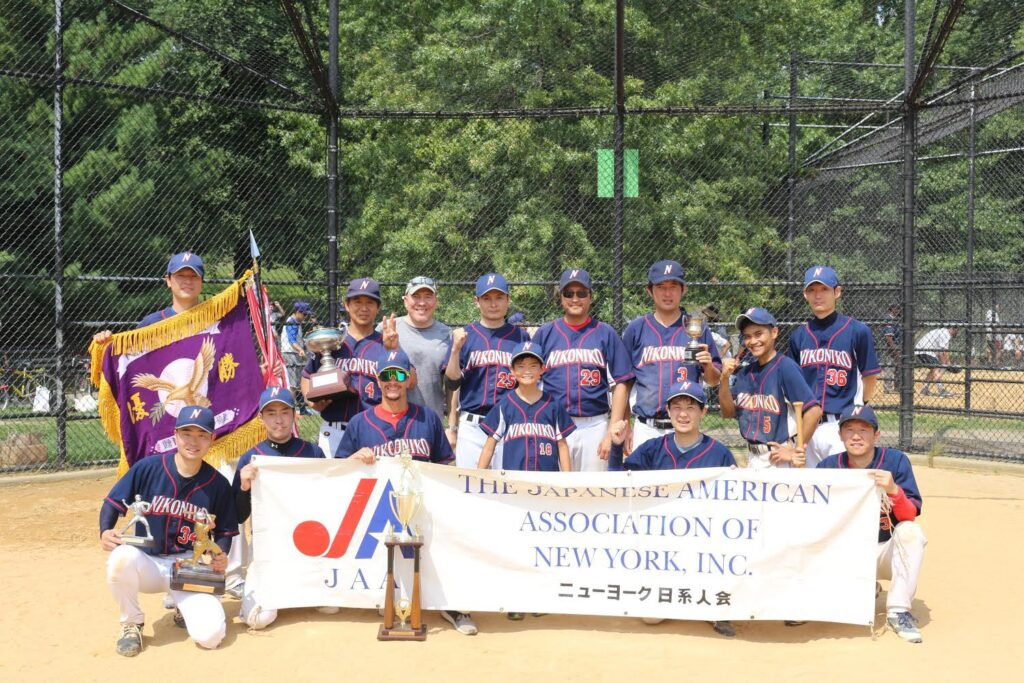

A photograph of the championship team Niko Niko in 2016, one of 16 teams that competed in the annual summer tournament organized by the Japanese American Association of New York (JAA). Every summer, from May through August, the annual Japanese American Association of New York baseball tournament continues the long tradition of amateur baseball games in the New York Japanese community. Founded in 1986 by Shuji Kato, chairman of the Sports Committee of the JAA, the tournament creates an atmosphere of lively competition between players of all levels, ages, and walks of life. In 1990, Taro Nakayama, then Minister of Foreign Affairs of Japan, visited the tournament and donated the Foreign Ministers’ Cup. Every year since the Cup is presented to the winner of the tournament by the President of the JAA alongside the Ambassador of the Consulate-General of Japan in New York.

In 2017, Kyle Higashioka (b. 1990), a yonsei, joined the iconic New York Yankees. Six years into his career with the Yankees, on February 7, 2023, Higashioka received the Thurman Munson Award. Named after the famed Yankees catcher Thurman Lee Munson (1947-1979), the award is presented annually to professional and Olympic athletes in recognition of their community service and athletic achievements. Higashioka was honored with the award for his time volunteering with the MLB Youth Academy in his hometown of Huntington Beach, California. He also volunteers with the Special Operations Warrior Foundation, an organization that offer post-secondary educational opportunities to the children of fallen Special Operations personnel and Medal of Honor recipients.

In the seaside city where Higashioka grew up, he did not have Japanese American friends. His friendship with fellow Yankees player Masahiro Tanaka, who relied on a Japanese-English interpreter to speak with his teammates, made Higashioka realize the connection to his ancestry he was missing. He started taking language lessons. In an interview with The New York Times on March 6, 2017, Higashioka said, “The rule of thumb is they don’t really consider you Japanese unless you speak Japanese. I would be a lot more proud of being able to speak because I am part Japanese.”

Courtesy of The Japanese American Association of New York, Inc.

1) Courtesy of the Official MLB Twitter account MLB Develops (@MLBDevelops). February 7, 2023.

2) Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Courtesy of Bobby Valentine.

A 2017 photograph of young Japanese baseball players from Iwate City posing with a Japanese American Association of New York (JAA) banner in New York City. The Japanese American Association of New York, alongside Bobby Valentine’s Sports Academy and the Kizuna Foundation, hosted ten middle school baseball players from Iwate, a prefecture on the northeastern coast of Japan, to participate in a baseball training camp and tournament with young U.S. baseball players. Part of a program called “Bobby Magic 2017,” the game was a continuation of the organizers’ efforts to promote healing among young survivors of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Bobby Valentine and the JAA sponsored teams of young players from Japan’s Tohoku region to visit New York, as well as sending a team of young Americans from Connecticut to play in Tohoku. It was an afternoon that reaffirmed baseball is a universal language and joy across cultures.

JAPANESE AMERICAN HERITAGE NIGHT

A photograph of the Japanese American Day at Candlestick Park in San Francisco celebrated before the start of a game between the New York Mets and San Francisco Giants on May 17, 1998. Left to right (back row) shows the San Francisco Giants manager Dusty Baker, New York Mets manager Bobby Valentine, Mets starting pitcher Masato Yoshii, Nisei Baseball Research Project (NBRP) Director Kerry Yo Nakagawa, actor and comedian Pat Morita (1932–2005), and Giants mascot Lou Seal. For Pat Morita, the moment was significant; the first time he experienced live baseball was during World War II in the Gila River concentration camp where he and his family were imprisoned.

The second photograph captures Japanese Consul General Mikio Mori after throwing out the ceremonial first pitch at Citi Field on August 25, 2022. To his left is Mets pitcher Max Scherzer, and to his right is former Mets pitcher Masato Yoshii. The ceremony before the New York Mets’ home game against the Colorado Rockies was part of a Japan-U.S. Baseball History Night event celebrating the 150th anniversary of baseball’s arrival in Japan from the United States.

The third image is an advertisement for baseball caps that will be distributed at the Japanese Heritage Night on August 25, 2023 at Mets Stadium. The game will be against the Los Angeles Angels and will feature Shohei Ohtani, who led Japan’s national baseball team to victory in the 2023 World Baseball Classic. The event celebrates 150 years of international exchange between the United States and Japan through baseball and aims to increase interest and momentum in exchanges between Japanese and American citizens.

Special Note: Work in Progress

This exhibit is a work in progress and will continue to expand as the Digital Museum receives new Japanese American baseball ephemera and stories from the community. Look for expanded content covering New York nikkei baseball between the 1940s and 1980s in the Fall of 2023.

Special Thanks

Contributing Author

Thomas Martin, PhD, is a professor of history and foreign languages at SUNY-Sullivan. He received the SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Teaching Excellence, and is the faculty advisor to the Asian-American Friendship Club. He has written for the New York Times, Hokkaido Shimbun, Svenska Dagbladet, and presented papers on Japanese-American History at the Association of Asian American Studies in San Francisco, Evanston and Portland

Research Contributors

Kerry Yo Nakagawa, director of the non-profit Nisei Baseball Research Project (NBRP)

Bill Staples, baseball historian and author

Institution

Nisei Baseball Research Project (NBRP)

Sources

Baba, Scott. “LENN SAKATA RETURNS TO HIS FIRST LOVE.” The Hawaii Herald, 18 June 2021, https://www.thehawaiiherald.com/2021/06/18/sports-lenn-sakata-returns-to-his-first-love/. Accessed 5 Dec. 2022.

Balsden, Cheryl. Seabrook Farms. Charleston, Arcadia, 2007.

“BUSHWICKS TO OPEN BALL SEASON AGAINST LANCASTER RED ROSES.” The Nassau Daily Review,

12 May 1931, p. 12. NYS Historic Newspapers,

https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn95071428/1931-03-12/ed-1/seq-12/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2022.

“CHINESE TO CLASH WITH CYPRESS HILLS TO-MORROW.” The Daily Standard Union: Brooklyn, 10 July 1915, p. 6. Brooklyn Newsstand, https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/543818951/?terms=baseball&match=1. Accessed 3 Oct. 2022.

“CHINESE NINE WINS.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 01 September 1915, p. 19. Brooklyn Newsstand, https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/54241833. Accessed 3 Oct. 2022.

Costello, Rory. “Mike Lum.” Society for American Baseball Research, SABR, 4 Jan. 2012, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/mike-lum/.

Costello, Rory. “Ryan Kurosaki.” Society for American Baseball Research, SABR, 9 Apr. 2020, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ryan-kurosaki/.

Costello, Rory. “Lenn Sakata.” Society for American Baseball Research, SABR, 4 Jan. 2012, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/lenn-sakata/.

Crowell, Paul. “MAYOR PROTESTS JAPANESE IN EAST: HE OPPOSES SHIFTING OF FORMER PACIFIC COAST RESIDENTS – SEES MILITARY PERIL HERE.” New York Times, 27 Apr. 1944, p. 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers, Accessed 3 Jan. 2023.

Fitts, Robert K. Banzai Babe Ruth Baseball, Espionage, & Assassination during the 1934 Tour of Japan. University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

Fitts, Robert K. Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers. University of Nebraska Press, 2020.

Fitts, Robert K. Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer. UNIV OF NEBRASKA Press, 2020.

Fitts, Robert K. Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball. University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

“Former Dodger, Royal Nomo Retires from Baseball.” ESPN.com, ESPN, 18 July 2008, https://www.espn.com.sg/mlb/news/story?id=3494534.

Franks, Joel S. From Honolulu to Brooklyn: Running the American Empire’s Base Paths with Buck Lai and the Travelers from Hawai’i. Rutgers University Press, 2022.

Gustkey, Earl. “WARMING UP TO WALLY : Yonamine, First American to Play in Japan, Was Not an Instant Hit.” Los Angeles Times, 18 June 1989, WARMING UP TO WALLY : Yonamine, First American to Play in Japan, Was Not an Instant Hit. Accessed 3 Oct. 5, 2022.

Guthrie-Shimizu, Sayuri. “For Love of the Game: Baseball in Early U.S.-Japanese Encounters and the Rise of a Transnational Sporting Fraternity.” Diplomatic History, vol. 28, no. 5, 2004, pp. 637-662. JSTOR,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24914819. Accessed 6 November 2022.

Hayes, A. J. “A Major Minor League Accomplishment.” Asianweek, Sep, 2007, pp. 14. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/major-minor-leagueaccomplishment/docview/367319137/se-2.

“Hideo Nomo Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Rookie Status & More.” Baseball, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/n/nomohi01.shtml.

Inouye, Daniel H., and David M. Reimers. Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community in New York City, 1876-1930s. University Press of Colorado, 2019.

Kaegel, Dick. “Reds Route Cardinals, 6-0.” St. Louis Post Dispatch, 1 June 1975, p. 41. Newspapers.com, https://stltoday.newspapers.com/image/140703379. Accessed 6 Dec. 4, 2022.

Kaneko, Gemma. “Kurt Suzuki Has Advice for Asian American Kids Who Want to Make It in the Big

Leagues.” CUT4, MLB.com, 9 May 2018, https://www.mlb.com/cut4/kurt-suzuki-talks-asian-american-experience-inmlbc275219692#:~:text=Suzuki%20didn’t%20really%20have,with%20the%20Reds%20in%201956.

“Lenn Sakata Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Rookie Status & More.” Baseball Reference,https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/sakatle01.shtml.

Lieb, Frederick G. “Baseball – The Nation’s Melting Pot.” Baseball Magazine, Aug. 1923, p. 393.

Lieser, Ethen. “Sakata: A Life in the State of Baseball.” Asianweek, 9 Aug. 2001, p. 20. Asianweek Database Project, https://database.asianweek.com/paperPage?date=2001-08-09&page=20&showPage=1. Accessed 7 Dec. 2002.

“M’GRAW’S MIND.” SPORTING LIFE, 25 Feb. 1905, p. 8. LA84 Foundation,

https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll17/id/37818/rec/8. Accessed 4 Oct. 2022.

Murray, Feg. “Feg Murray Says.” The Ogdensburg Republican-Journal, 24 Feb. 1928, p. 6. NYS Historic

Newspapers, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn84024315/1928-02-24/ed-1/seq-6/. Accessed 5 Dec. 2022.

Nakagawa, Kerry Yo. Japanese American Baseball in California: A History. The History Press, 2014.

Nakagawa, Kerry Yo. Through a Diamond, 100 Years of Japanese American Baseball. Rudi Pub., 2001.

“Nisei Ballplayers, Attention!” Rohwer Outpost, 24 July 1943, p. 8. Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-143-82/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Otake, Gary T. “Japanese American Baseball History Project – National Japanese American Historical Society.” NJAHS, 30 Sept. 2015, https://www.njahs.org/japanese-american-baseball-history-project/.

Regalado, Samuel O. Nikkei Baseball Japanese American Players from Immigration and Internment to the Major Leagues. University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Russo, Neal. “Cards Tossed For A 10-1 Loss.” St. Louis Post Dispatch, 15 May 1975, p. 19.Newspapers.com, https://stltoday.newspapers.com/image/140709303. Accessed 6 Dec. 4, 2022.

Russo, Neal. “What’s in a Name? Good Pitching.” St. Louis Post Dispatch, 13 June 1975, p. 29. Newspapers.com, https://stltoday.newspapers.com/image/140701423. Accessed 6 Dec. 4, 2022.

“Sadaharu Oh Japanese Leagues Statistics.” Baseball, https://www.baseball-

reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=oh—-000sad.

“SAFE AND SANE THE NATION OVER: THE FOURTH MARKED BY STILL FEWER…” New York Times, 5

Jul. 1911, p. 4. ProQuest Historial Newspapers, Accessed 4 Jan. 2023

Smith, C. R. “OPENING GAME HERE TOMORROW.” The East Hampton Star, 25 May 1928, p. 1. NYS

Historic Newspapers, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn83030960/1928-05-25/ed-1/seq-1/.

Accessed 1 Aug. 2022.

“SOFTBALL GAMES OPEN THIS SUNDAY.” The Nisei Weekender, 30 May 1946, p. 1. Densho,

https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-358/ddr-densho-358-6-mezzanine-328b02ba6e.pdf.

Staples, Bil. Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer. McFarland & Co., 2011.

“Tatsuno Will Play in Japan.” The Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 5 July 1979, p. 53.

https://www.newspapers.com/image/272007586

Varner, Natasha. “Baseball in American Concentration Camps: History, Photos, and Reading

Recommendations.” Densho, 5 Apr. 2016, https://densho.org/catalyst/baseball-world-war-ii-concentration-camps-photo-essay-brief-history/.

Whiting, Robert. You Gotta Have Wa. Vintage Books, 2009.