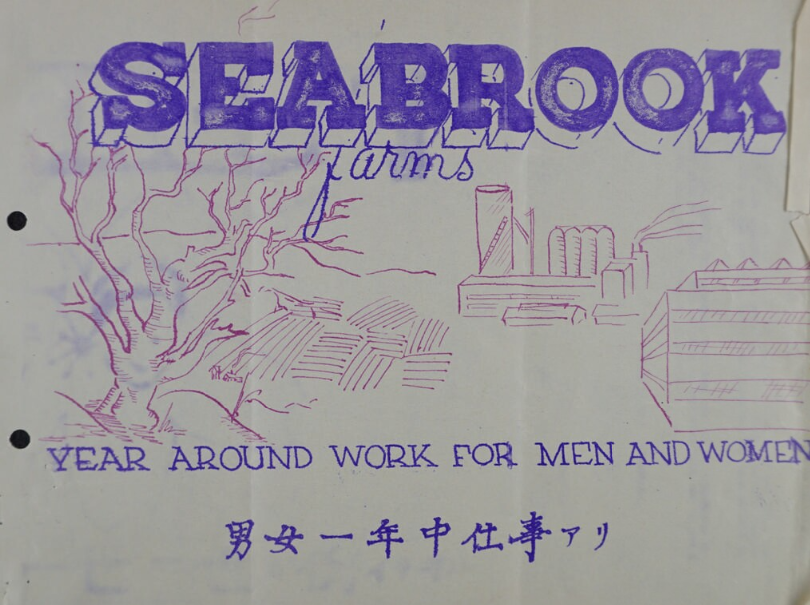

Between 1939 and 1945, Seabrook Farms and other agricultural enterprises in southern New Jersey, including the Campbell Soup Company, experienced a substantial influx of seasonal migrant workers brought on board to address the escalated wartime production demands. These workers hailed from various islands within the British West Indies, including Barbados and Jamaica, as well as from Puerto Rico and the United States South. Seabrook Farms leveraged its status as a wartime contractor, utilizing the War Manpower Commission, a federal agency established during the war, and the United States Information Service, a network of employment agencies, to manage its recruitment needs. From 1943 until the war’s conclusion, the War Relocation Authority, established to administer internment, initiated a gradual process of releasing internees. After pledging “unqualified allegiance to the United States” in a loyalty questionnaire, Issei and Nisei internees became eligible for supervised work release to locations east of the Mississippi River.

More than 2,500 Japanese Americans were relocated to Seabrook Farms as part of this initiative from the concentration camps. In addition, approximately 300 Japanese Peruvians were forcibly relocated to Seabrook Farms in 1946. These individuals were among those affected by the Peruvian government’s massive arrests and deportations of Japanese Peruvians to camps, primarily in Crystal City, Texas, without warrants or judicial oversight, as part of a bilateral agreement between the two countries. At the end of the war, Peru denied re-entry to Japanese Peruvians. Seabrook’s perspective aligns with the prevailing attitudes of many white employers during this period, who often stereotyped released Nisei and Issei internees as “more efficient, intelligent, and industrious workers” compared to Black Southerners. This perception was further influenced by the belief that internees were less likely to provoke racist hostility from local whites. While Seabrook marketed his company as a haven free of racial discrimination, he also perpetuated the idea that Japanese Americans were a “model minority” group whose docility and willingness to follow orders made them ideal workers.

Masaru Edmund Nakawatase was born in 1943 in a concentration camp in Poston, Arizona, and grew up in Seabrook Farms, New Jersey, where his parents and many Japanese Americans had relocated from the concentration camps. Through this experience, Nakawatase became a civil rights activist, joining the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1963 and devoting most of his professional life to the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), first as a community organizer in South Jersey and then as a national staff member of the Third World Coalition (TWC). The TWC was a caucus of AFSC staff and committee members of color that oversaw Native American affairs nationally from 1974 to 2005. Nakawatase currently serves as a trustee of the Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center.

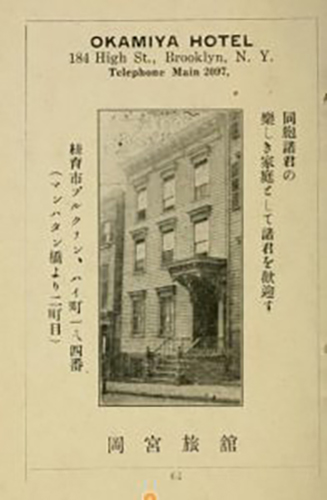

In mid-1944, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) established a hostel in Brooklyn Heights, which housed several hundred resettlers for a period of two years. This was followed by the opening of additional hostels. Despite relocating to more permanent accommodations, a significant number of resettlers continued to reside within two small Japanese American enclaves. One such community was situated on the West Side, spanning from 106th to 110th Streets, in proximity to the Japanese American Methodist Church. This area was informally referred to by a local as the “pickled plum district.” A second group settled in Inwood, located near the northernmost tip of Manhattan, where another Japanese American church established its operations. In the context of other resettlement locations, a pervasive pattern of discrimination against the newcomers emerged, both officially and unofficially. New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia exhibited overt animosity towards Japanese Americans. In April 1944, when the WRA unveiled its plans to establish a hostel in Brooklyn, LaGuardia vehemently opposed the initiative and explicitly stated that resettlers from the camps were not welcome in New York.

The Japanese Mutual Aid Society (Nihonjin Kyosaikai) was established in 1907 by Dr. Toyohiko Takami. In 1914, the organization underwent a transformation, becoming the Japanese Association of New York (New York Nihonjinkai), a development founded by Dr. Takami, Dr. Jokichi Takamine, and other prominent community leaders. During World War II, the organization was disbanded, but it was reconstituted shortly thereafter to serve primarily as a relief agency. It sent food and clothing to Japan through the American Friends Service Committee’s Licensed Agency for Relief in Asia (LARA). As conditions in Japan improved, the organization shifted its focus to addressing local needs, leading to its merger with the Japanese American Welfare Society (1946 – 1952), which was established in 1946 with help with Issei who were detained at Ellis Island such as Rev. Akamatsu, Dr. Emy and Nisei such as Dr. Masahiko Takami, a son of Dr. Toyohiko Takami. This collaboration enabled the committee to assist Japanese Americans and Japanese individuals in relocating and settling in the greater New York area following their release from concentration camps across the United States. A significant legal development that contributed to the organization’s mission was the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which legalized citizenship for Japanese nationals. In the same year, the Japanese American Welfare Society and the Japanese Association merged to form the Japanese American Association of New York, which continues to expand and support the Japanese and Japanese American communities.

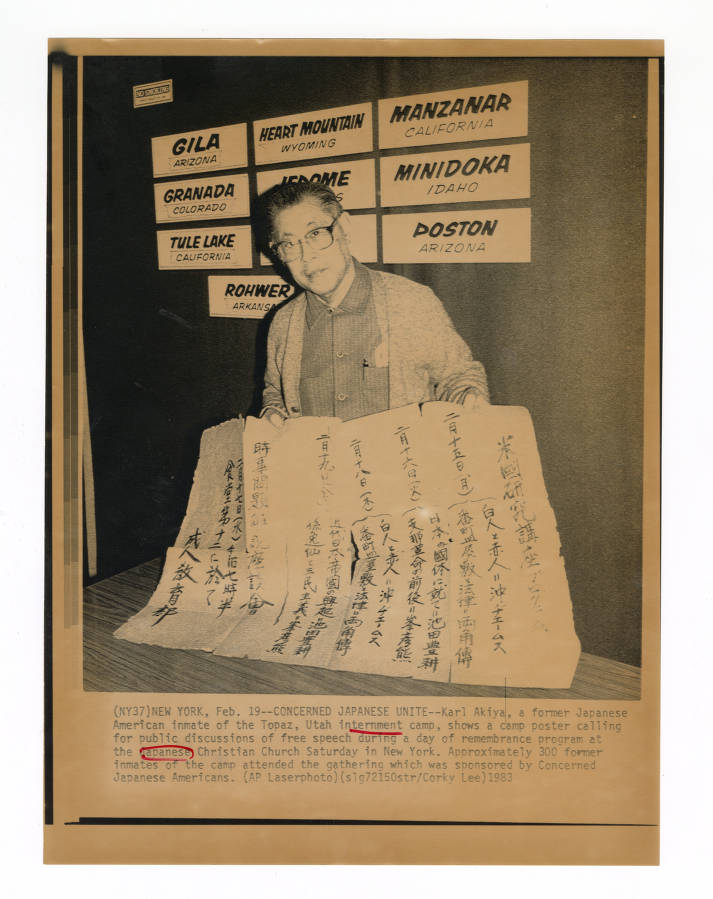

Isaku Kida‘s departure from Japan in 1932, subsequent relocation to New York, and involvement in the OSS Military Intelligence Group are notable milestones in his career. He was instrumental in the establishment of Hokubei Shimpo and the New York Committee for Relief to Japan following the war. The Hokubei Shimpo published the New York Binran from 1948 to 1949, including “War Time Activities,” which reported on the activities of the JACD, the 442nd Combat Team, Japanese organizations, and communities in New York and published biographies of notable Japanese New Yorkers. Kida collaborated with Karl Ichiro Akiya, an activist in the labor and Japanese communities in both the United States and Japan. While incarcerated at the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah, Akiya was released to serve as a language instructor at the U.S. Army Japanese Language School at the University of Michigan. Akiya was a member of the Japanese American Citizens League, the Furniture Workers Union, and the Communist Party of the U.S.A.

In the aftermath of the war, Rev. Hozen Seki returned to the New York Buddhist Church, where the congregation underwent substantial growth and prosperity. This period marked the addition of a Sunday school to the Japanese school and the congregation’s sustained engagement with the Japanese, Japanese American, and New York communities.

Toru Matsumoto, who had previously served as general secretary of the Japanese Student Christian Association (JSCA) and collaborated with the World Student Service Fund to assist students during the war, obtained a doctorate in education from Columbia University following the war’s conclusion. In mid-1946, he published A Brother is a Stranger, which discussed the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans and offered a portrait of Matsumoto’s own experiences in East Coast concentration camps.

In 1948, the Whitney Museum of American Art hosted a retrospective exhibition of the works of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, an artist and leader of the JACD. In 1952, Kuniyoshi was selected as one of the artists to represent the United States at the 26th Venice Biennale. However, he never gained his US citizenship and died in 1953. On the other hand, Kuniyoshi’s friend Isamu Noguchi’s design was not selected for the monument (cenotaph) in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park because of his American nationality. Between 1932 and 1972, Leo Amino and Noguchi were the most represented artists of color in the history of the Whitney’s Annual Exhibitions for sculpture.

From 1939 to 1942, Miné Okubo assisted with several murals commissioned by the Federal Art Project and produced over 2,000 drawings and sketches of daily life in the WRA camps at Tanforan and Topaz. Okubo was released from the concentration camp when Fortune magazine hired her as an illustrator, and she moved to New York. Her commission from Fortune was completed in 1944 and depicted scenes of Japanese life in Imperial Japan, even though Okubo was a native of California and had never visited Japan. In 1946, she published a book titled Citizen 13660, which detailed her experiences as a prisoner in concentration camps in California and Utah.

In the aftermath of the war, Nisei and Sansei (grandchildren of the Japanese-born emigrants) individuals persisted in their efforts as civil rights activists, challenging the pervasive racial discrimination that targeted Asian communities. Among these committed individuals were notable figures in New York, such as Mitziko Sawada, an academic historian and author of Tokyo Life, New York Dreams, which is a bicultural study focusing on Japanese immigrants in New York, Kazu Iijima and Minn Matsuda established the foundation for Asian Americans for Action in 1969, and Yuri Kochiyama, a human rights activist worked with Malcolm X and Black Power organizations and leader of the Asian American and redress movements. Suki Terada Ports is a prominent AIDS advocate who was raised in Morningside Heights, New York, during the period of heightened anti-Japanese racism that occurred in tandem with World War II. This historical era has imbued her with a rich set of personal narratives and a distinctive perspective on her cultural and ethnic identity. A lifelong resident of Morningside Heights and Riverside Drive near Columbia University, Suki has dedicated her life to advocating for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) New Yorkers, and her endeavor continues to the present day.

In the late 1940s, the Japanese garden at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which had been created in 1915 by Takeo Shiota, who passed away in a concentration camp in South Carolina, underwent restoration by Japanese American gardener and horticulturist Frank Masao Okamura following his release from a concentration camp in California. In 1943, George Yuzawa was released from the Amache Internment Camp in Colorado and employed by a florist in New York. After George attended City College of New York from 1946 to 1947, earning a certificate in foreign trade on the G.I. Bill, he assisted his father in operating the floral business, which would eventually become highly prosperous. Yuzawa’s community involvement included serving as vice president, board member, and committee chair of the Japanese American Association of New York (JAA) . During this period, he played a pivotal role in organizing a diverse array of Japanese cultural, educational, and preservation activities in New York City. In 1982, Yuzawa and the Japanese American Association of New York collaborated to establish the annual spring Cherry Blossom Festival at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which was held annually until 2020.

As a florist, Yuzawa cultivated cherry tree seedlings and participated in their planting in Flushing Meadows Corona Park. In a spirit of continuity and in collaboration with the City of New York Parks and Recreation, JAA has the pride of carrying on his legacy by organizing the Sakura Matsuri Cherry Blossom Festival at Flushing Meadows Corona Park, the Queens Museum, and the Theatre at the 1939 and 1964 New York World’s Fair site.

References

Pegler-Gordon, Anna. “‘New York Has a Concentration Camp of its Own’: Japanese Confinement on Ellis Island During World War II,” Journal of Asian American Studies 20.3 (Oct. 2017).

Matsumoto, Toru and Marion Lerrigo, A Brother is a Stranger . New York: John Day Co., 1946.

Mizutani, Shiozo, Nyuyoku Nihonjin Hattenshi (New York: Nyuyoku Hihonjinkai, 1921)

Hokubei Shimpo, ed., Nyuyoku Binran, 1948-1949 (New York: Hokubei Shimpo, 1948),

The Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Summer 1998.

Greg Robinson, “Nisei in Gotham: Japanese Americans in Wartime New York,” Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies, Vol. 30 (2005), pp. 581-595.

Greg Robinson, The Unsong Great: Stories of Extraordnary Japanese Americans, University of Washington Press, 2020

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Eiichiro Azuma, Issei in New York, 1876 – 1941, Japanese American National Museum Magazine

Invisible Restrains: Life and Labor at the Seabrook Farms, online exhibit curated by undergraduate and graduate students, supervised by Professor Andy Urban, Rutgers University, 2015

This exhibit has been organized by the Digital Museum of the History of Japanese in New York.

This exhibit has made possible with support from:

The J.C.C. Fund

The Consulate General of Japan in New York

The SMBC Global Foundation

The Asian American Studies Center at UCLA, and the Aratani C.A.R.E. Award

Exhibit Committee:

Shunichi Homma, Susan Onuma, Daniel H. Inoue, Haruko Wakabayashi, Lane Walker

Project Manager: Mac Gill

Curator: Yuka Yokoyama

SPECIAL THANKS

Greg Robinson, Professor of History at l’Université du Québec À Montréal

Michiyo Noda, Japanese American Association of New York

Eiko Aono and Akemi Takeda, Volunteers at the JAA Archive

Jamie Henricks, Archivist at the Japanese American National Museum

Genji Amino, Director, Leo Amino Estate

Kathryn Bannai, Board, Japanese American National Museum

The materials on display are provided by:

The Japanese American Association of New York

The Lutnik Library at Haverford College

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Discover Nikkei

Densho

The Japanese American National Museum

New York Public Library

UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

The National Archives

American Friends Service Committee