At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, a significant number of Japanese American students were enrolled in educational institutions across the United States. In response to the evacuation, local groups endeavored to facilitate the prompt transfer of students to educational institutions situated east of military zones. To that end, a Student Relocation Committee was established in Berkeley on March 21, 1942. This committee successfully coordinated the evacuation of approximately 75 students to educational institutions outside the restricted area. However, the majority of students opted to relocate with their families to assembly centers. In May 1942, Clarence Pickett of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) established The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, a nongovernmental committee to identify institutions of higher education in the eastern and midwestern regions where Japanese American students could pursue their education.

Japanese Student Relocation, An American Challenge, 1942. Courtesy of American Friends Service Committee

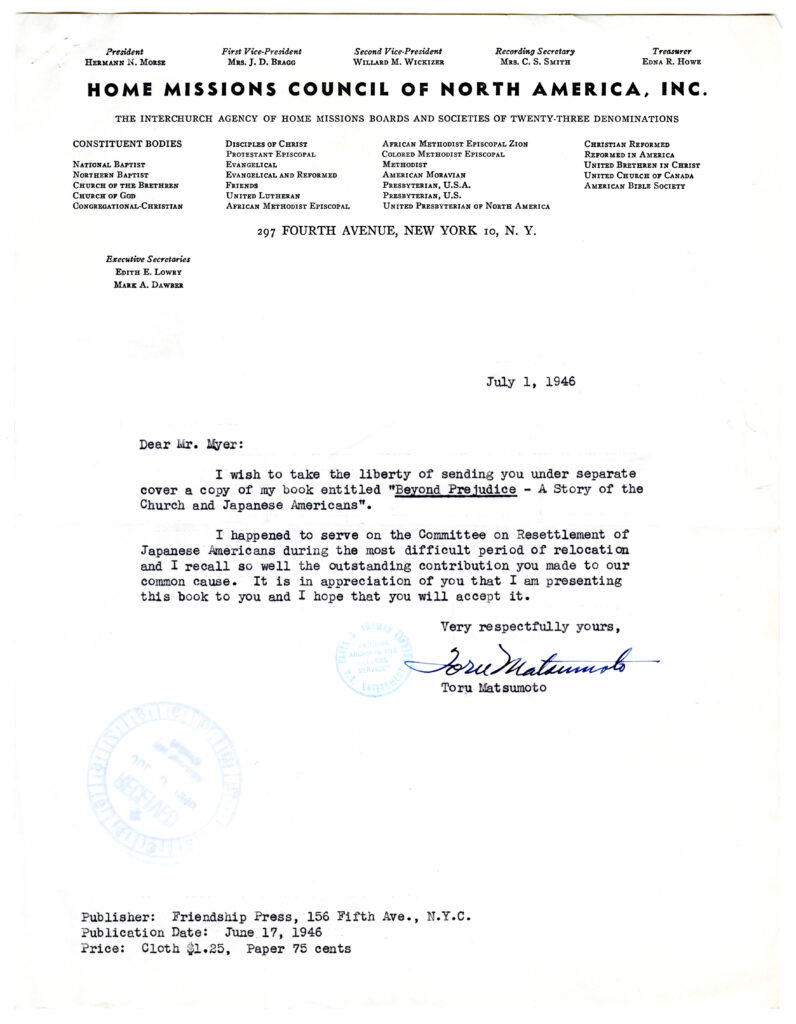

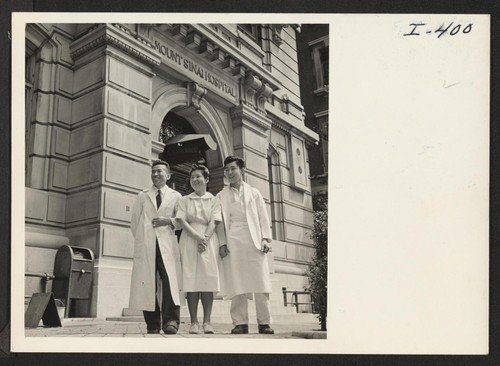

Toru Matsumoto was interned at Ellis Island and Camp Upton in New York and was subsequently relocated to Fort Meade in Maryland. In the late months of 1942, after his release from internment, he was designated as executive assistant to George E. Rundquist, the Secretary of the Committee on Resettlement of Japanese Americans for the Federal Council of Churches and the Home Missions Council of North America. Matsumoto’s activities also included collaboration with the International Board of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Concurrent with his involvement in Japanese American Christian Association (JSCA) as secretary general was his collaboration with The World Student Service Fund, where he contributed to fundraising efforts aimed at supporting students. Matsumoto’s endeavors extended to visiting concentration camps, where he encouraged young Japanese Americans to take advantage of NJASRC’s programs and pursue higher education beyond the confines of the camps.

How to Help Japanese American Student Relocation, published by the National Student Relocation Council, 1943. Courtesy of AFSC.

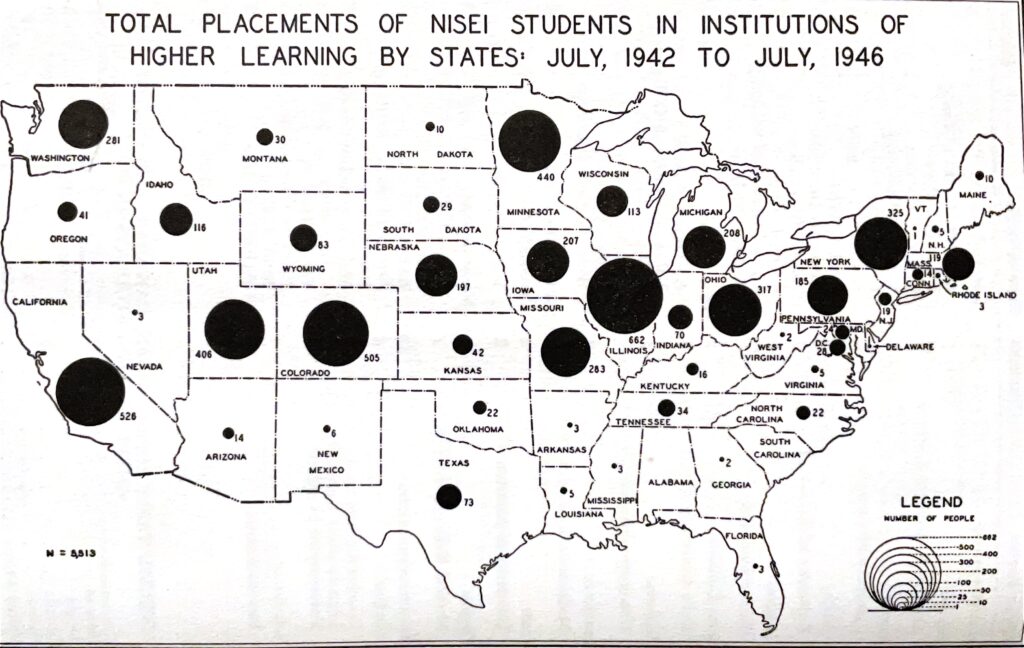

Within a year of its founding, by April 1, 1943, the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council had provided opportunities for more than 1,000 students to continue their education. According to the Council’s records, by the end of the war in 1945, more than 5,500 students had been placed in approximately 550 educational institutions in 46 states.

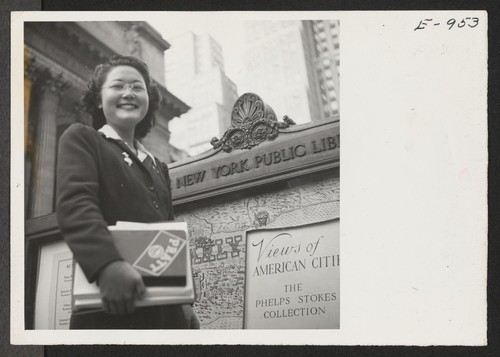

In New York, Alfred University, Chesbrough Seminary, Art Students’ League, Bard College, Barnard College, Biblical Seminary in New York, Cornell University, New School of Social Research, Hunter College, Manhattanville, College of Sacred Heart, New York Institute of Photography, New York School of Social Work, New York University, Otsego School of Education, Pace Institute, Packard Business College, Pratt Institute, Rochester Institute, Rochdale Institute, Russell Sage College, Syracuse University, Teachers College, Traphagen School of Fashion, Tully High School, Union College, Union Theological Seminary, University of Buffalo University of Rochester, and Vassar College joined the effort, and over 320 students were relocated to New York to pursue their education. A total of over 500 came to the East Coast from July 1942 to July 1946.

New York University, under the leadership of Chancellor Harry Woodburn Chase, notably enrolled more than a dozen Japanese American students. Chase firmly believed in the pivotal role of education in safeguarding democratic principles, fostering freedom of expression and academic freedom, and promoting racial and religious tolerance, global awareness, and minority education. Mitsuye Yamada (then Yasutake), a student at New York University during the war, went on to become a prominent figure in Japanese American poetry, essayism, feminism, and human rights activism. She was among the most outspoken Asian American writers to address the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans.

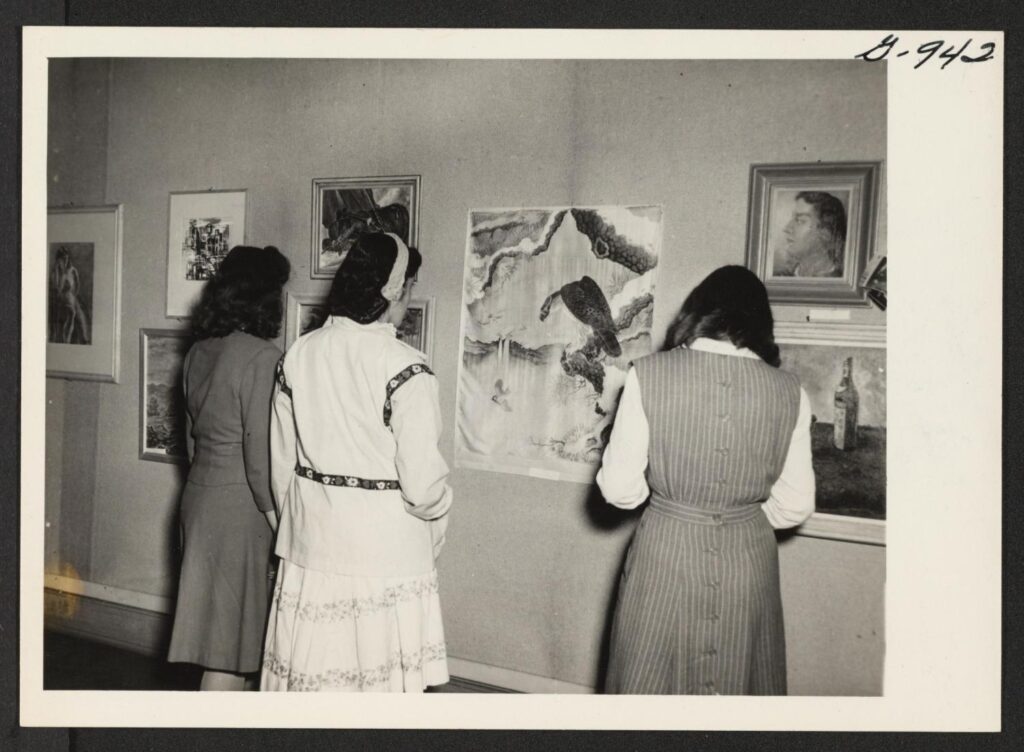

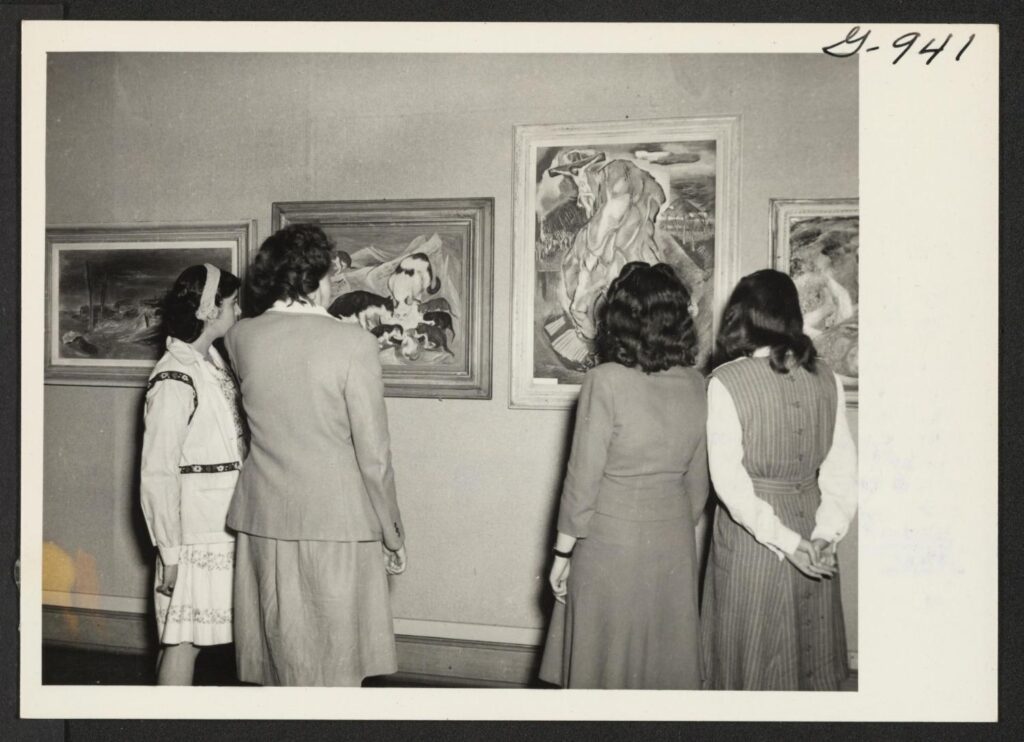

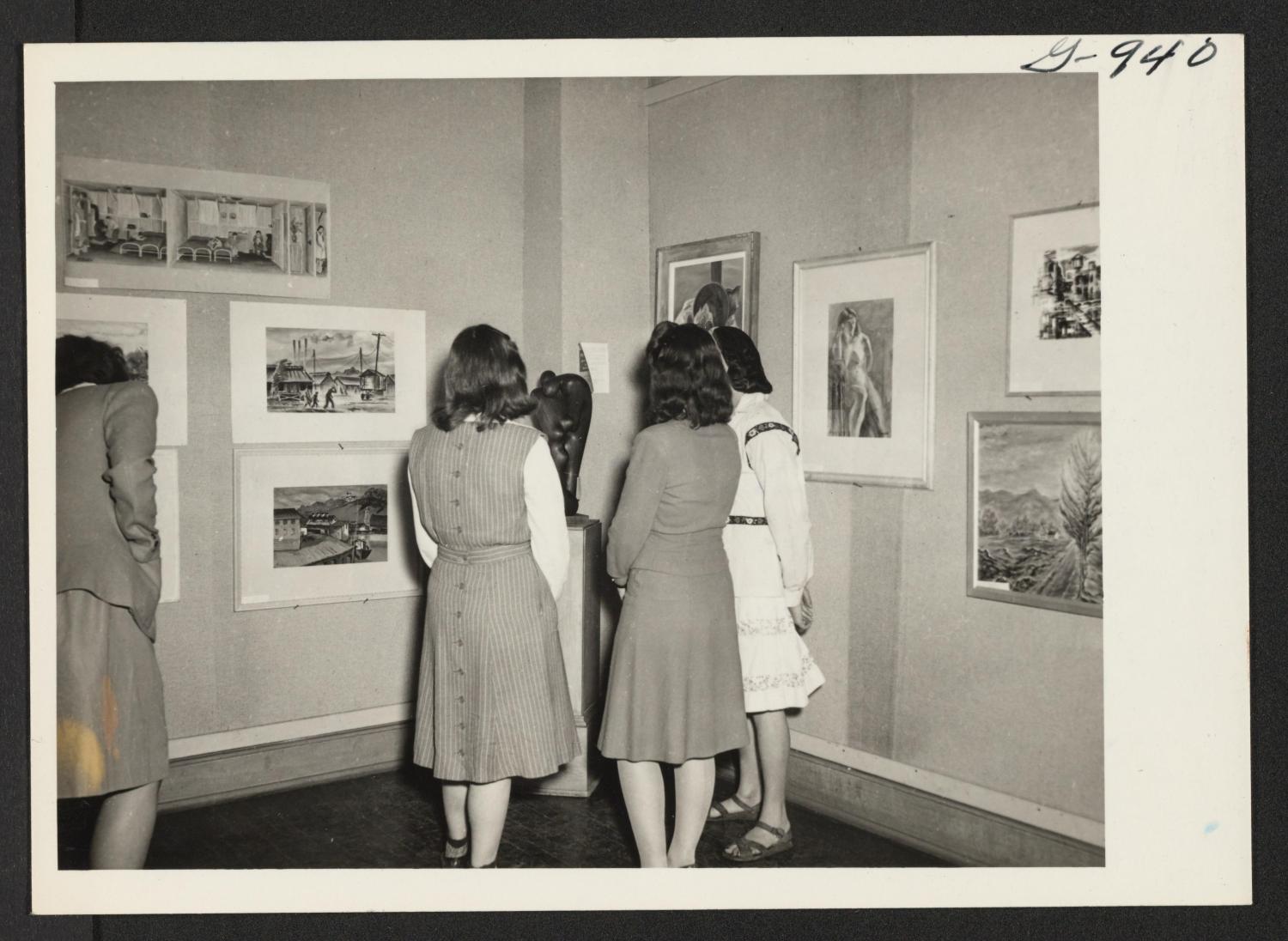

In 1945, the Newark W.R.A. office and a civil rights group, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) organized a traveling art exhibition of paintings and sculpture by Issei and Nisei New Yorkers, including JACD artists, Leo Amino, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Eitaro Ishigaki at the New Jersey College for Women, New Brunswick, New Jersey, attended by over a thousand people, including Japanese Americans and relocated students around the area.

In 1942, Kenji Kenneth Murase became one of the first three Nisei to be admitted to higher education institutions by the newly established NJASRC. After graduating from Temple University in 1944, Murase relocated to New York City, where he assumed a position as an aide in a social service agency. Subsequently, he enrolled in the School of Social Work at Columbia University, receiving his master’s degree in 1947. In 1952, Murase became the inaugural American Fulbright Scholar in Japan, where he served as a visiting professor of social welfare at Osaka University. Upon his return to the United States, Murase assumed a professorship in the Graduate School of Social Work at the University of Washington. In the late 1950s, Murase returned to Columbia University in New York to pursue his doctoral studies. Murase’s experience at the camp and his scholarship from the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, which facilitated his attendance at Temple University, had a profound impact on him. In 1980, he and other recipients established the Nisei Student Relocation Commemorative Fund with the aim of generating funds for college scholarships for children of Southeast Asian refugee families.

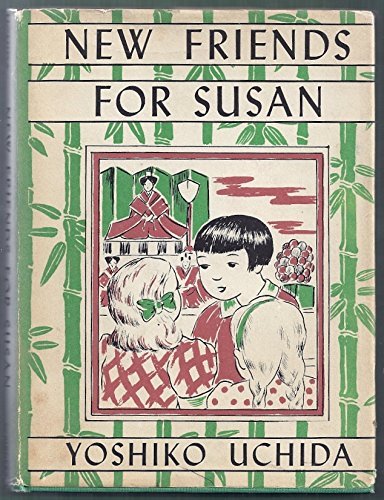

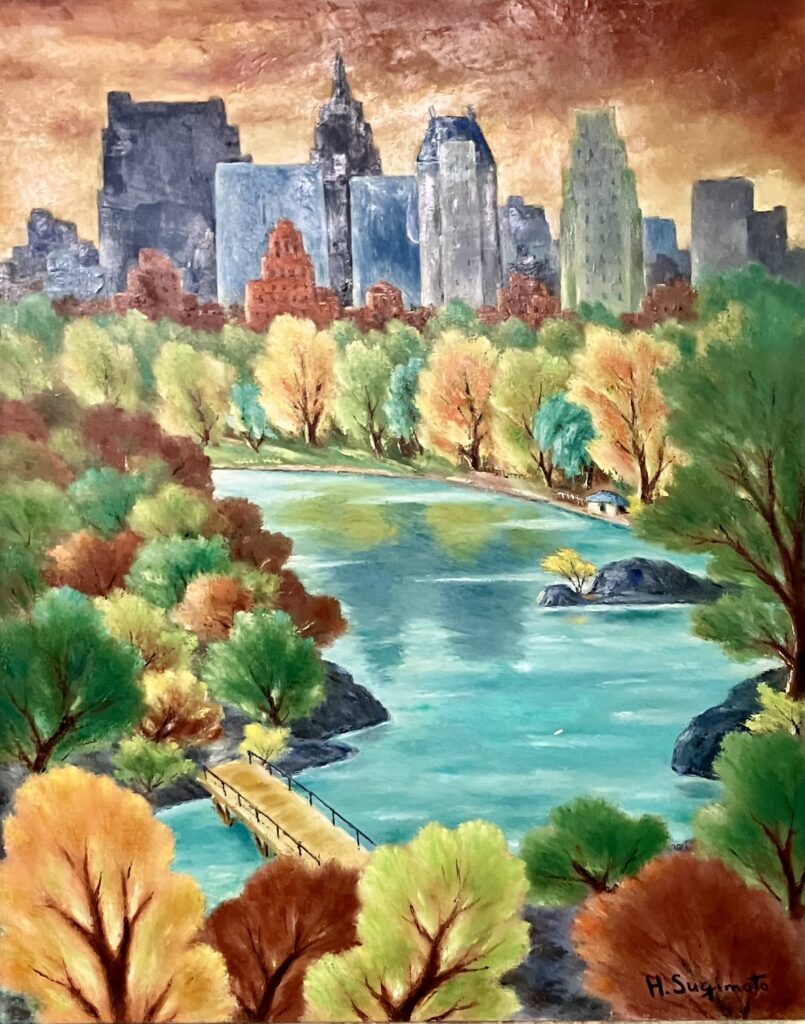

Yoshiko Uchida was among the students who were relocated from concentration camps to the East Coast. She pursued her studies at Smith College through the wartime student relocation program and subsequently taught at a Quaker school in Philadelphia for several years prior to relocating to New York. Uchida became a prominent figure in the discourse on the internment experience, openly discussing its implications and publishing books that focused on the Japanese American experience. Uchida collaborated with Henry Sugimoto, who also relocated from the camp, and provided the artwork for New Friends for Susan, one of her children’s books about a Japanese American girl.

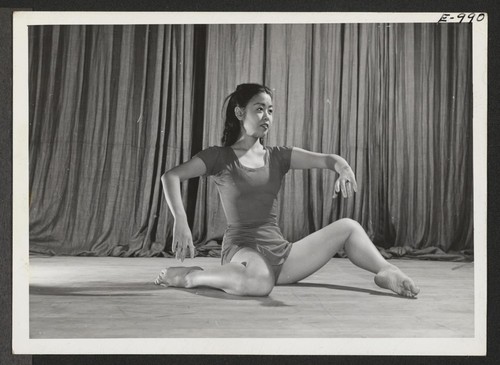

Sono Okamura, like Uchida, won a scholarship to Smith College in 1940, then moved to New York in 1943, where she began work as a copy editor for the Associated Press and joined JACD. Okamura presented and wrote about Nisei women who had settled in New York, including painter Mine Okubo, dancer Yuriko Kikuchi, silversmith Kikuko Miyakawa Cusick, illustrator Amy Fukuba, and interior designer Mary Daté, among others.