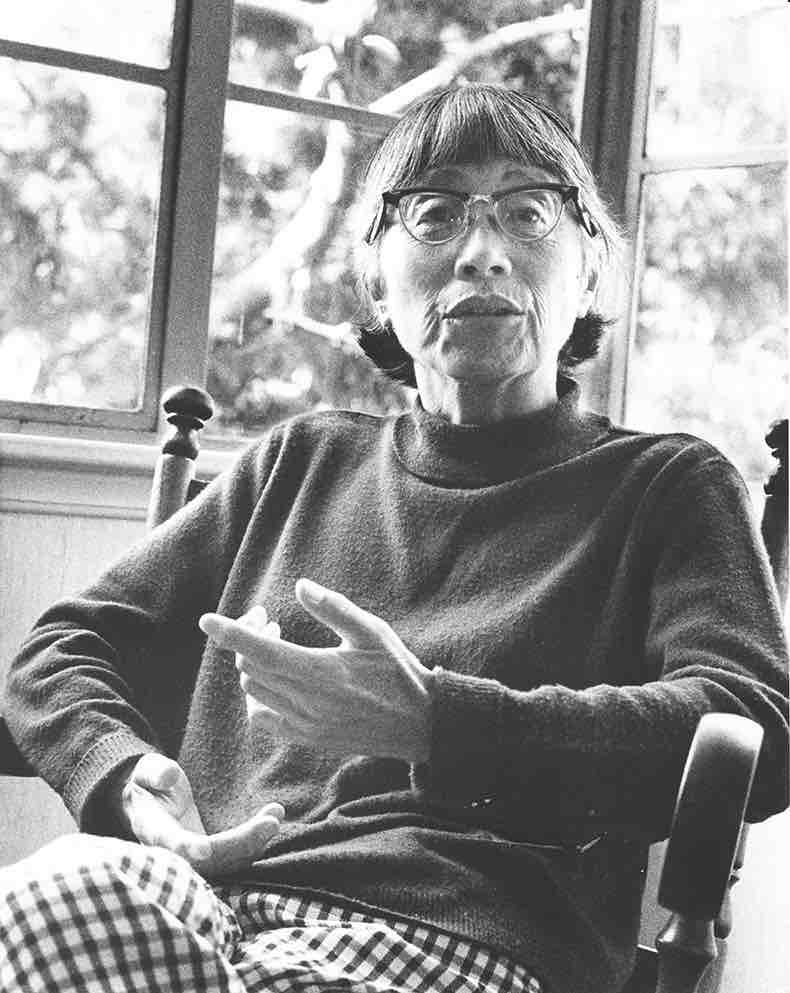

Prior to the war, the Japanese community in New York was divided between the pro-Tokyo and the progressives. In response to the potential threat of war, the progressives united to protect community members from dismissal due to discrimination, leading to the formation of the Committee for the Democratic Treatment of Japanese Residents in the Eastern United States. This coalition comprised artists and activists, as well as journalists. In August 1940, a coalition of Issei and Nisei, such as Larry Tajiri and Thomas Komuro, established the Committee for Democratic Treatment of Japanese Residents in the Eastern States. This organization was formed on the basis of a desperate effort to convince the American public that the Japanese community in the United States was not responsible for Japanese aggression in Asia and that they had no ill will towards the American people and their government. The organization’s inaugural president was Rev. Alfred Akamatsu, a young Japan-born minister of the Japanese Methodist Church of New York. The committee’s primary focus was on social service initiatives within the Japanese community, and it assisted individuals affected by the closure of Japanese businesses in obtaining unemployment insurance and inquired about employment assistance from churches and the government. The committee undertook a social study of the New York Japanese community to ascertain the most pressing service needs and protested discrimination against Japanese Americans in New York.

Interview with Rev. Alfred Akamatsu, pastor of the Japanese Methodist Church in New York, published in “The Christian advocate” after the end of World War II in the Pacific. California State University, Fullerton, University Archives and Special Collections

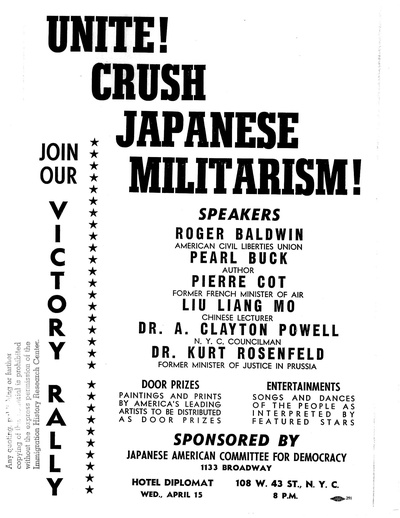

In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into the war, a substantial shift in the situation became evident. The Japanese Consulate in New York was closed, the Committee for the Democratic Treatment of Japanese Residents in the Eastern United States was dissolved, and the Department of Justice initiated the detention of numerous businessmen and community leaders at Ellis Island, citing concerns of potential disloyalty. These arrests encompassed Japanese nationals with no evidence of disloyalty to the United States, including Rev. Akamatsu and others. The mass detention of Japanese New Yorkers on Ellis Island had ramifications for the detainees themselves, their families, and the broader New York community. A number of detainees expressed a desire to return to Japan, while others, despite identifying as American, experienced a sense of alienation due to the pervasive anti-Japanese racism.

Many individuals found themselves in a state of internal conflict, grappling with their complex emotions and sentiments regarding their identity and belonging. There was a demonstrated lack of concern from New York City welfare officials regarding Japanese and Japanese Americans. Private agencies, including a Quaker organization, the Civilian Community Service Society of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), and the Church Committee for Japanese Work, appealed to Christian churches to assist in providing employment and housing for those whose lives were upended.

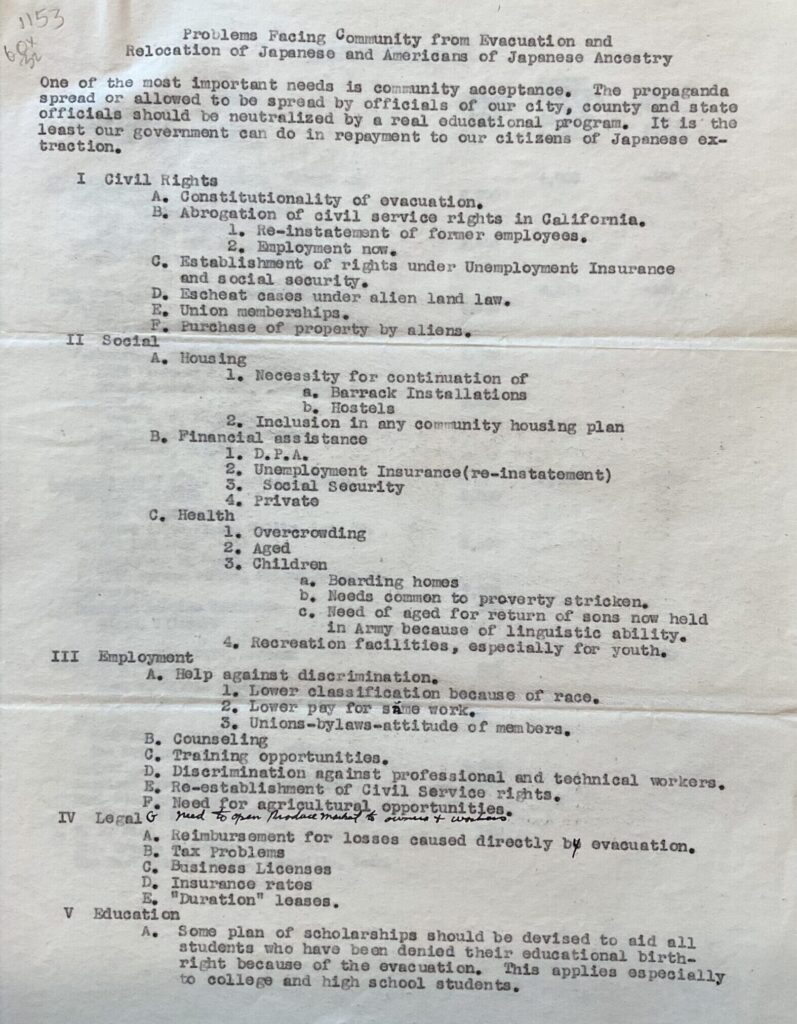

In response to these developments, a public meeting was convened and attended by 150 individuals, which led to the establishment of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy (JACD). The organization elected Thomas Komuro as its chairman, who established six subcommittees and initiated the publication of a regular newsletter. The newsletter featured a progressive, pro-democracy advisory board that included prominent figures such as Pearl S. Buck, Albert Einstein, and Franz Boas. In mid-March 1942, the JACD advocated for a federal agency to provide employment opportunities for Japanese Americans facing job discrimination. The JACD organized rallies to support the American war effort in World War II, helped Japanese Americans relocate in New York from concentration camps, and provided a platform for Issei and Nisei to convene and socialize. The JACD Newsletter, published monthly, disseminated information about the Nikkei communities in New York.

In early 1943, Nori Ikeda Lafferty relocated to New York and was hired as JACD’s first paid staff member. This prompted a group of fellow Nisei activists to congregate in New York, following Ikeda Lafferty’s lead. The JACD rapidly became predominantly comprised of Nisei members. In 1944, the Issei board members resigned, and the Nisei members were elected to lead the JACD. The JACD Arts Council was also established with the assistance of artists Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Isamu Noguchi. The council’s primary objective was to produce propaganda in favor of democracy and against the Japanese militarism of the time. New York-based writers and journalists participated in this initiative.

Japanese American Committee For Democracy News Letter, Vol. 2 No 2., November 1943. Courtesy of the Occidental College Library Special Collections

Minoru Yamasaki , a Nisei architect, became a representative of the Japanese Americans for Democracy Art Council and chairman of the organization coordinating the resettlement of Japanese Americans in New York City. Yasuo Kuniyoshi, a prominent artist, created a series of anti-war posters commissioned by the Office of War Information (OWI). In addition, he delivered a radio address to Japan that emphasized the importance of democracy. Chuzo Tamotzu was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and deployed to Southeast Asia. Isamu Noguchi, a resident of New York, was not subject to government evacuation orders. However, he voluntarily reported to the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona.

Leo Amino was one of the artists featured in the 1939 New York World’s Fair, along with Isamu Noguchi. Following Pearl Harbor, Amino’s New York home was searched, and he was interrogated by the Secret Service. For the duration of the war, he translated legal documents of the Japanese government. Amino was also on the executive committee of the JACD Arts Council which Noguchi and Kuniyoshi chaired.

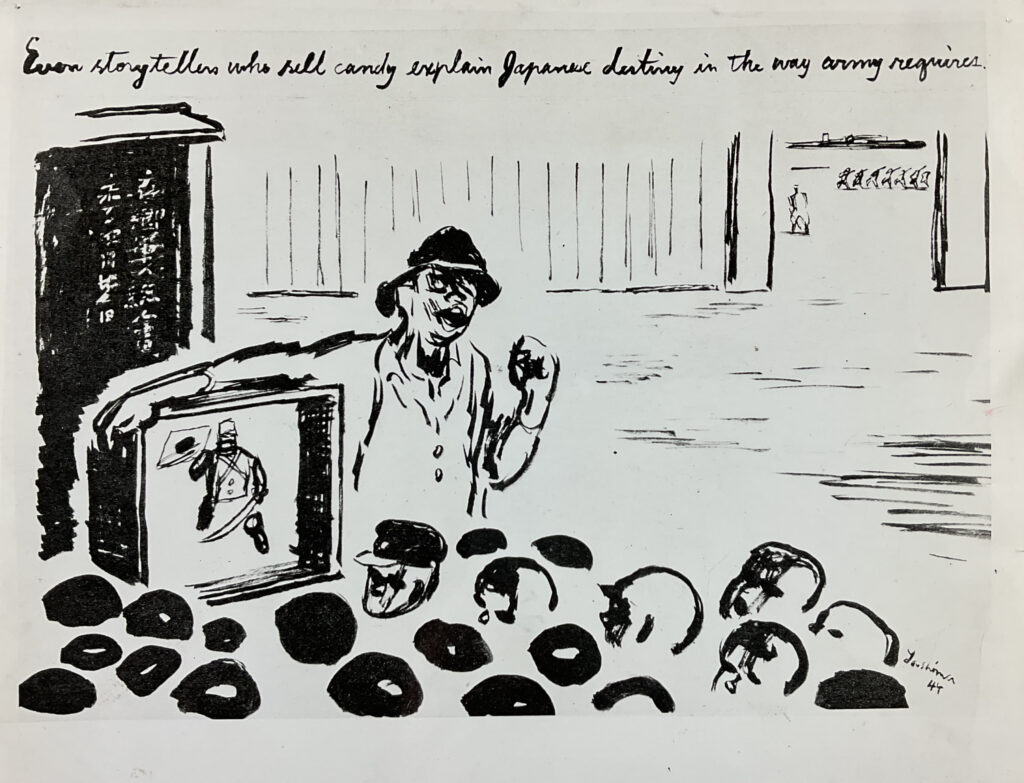

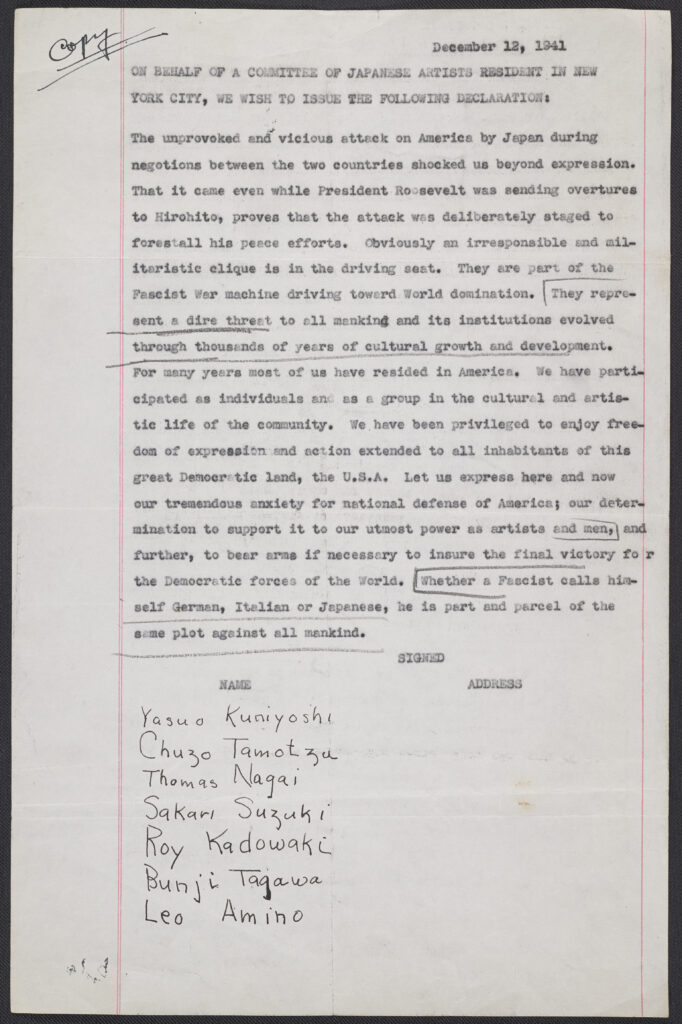

In December 1941, Amino, Kuniyoshi, Tamotsu, Noguchi, Thomas Nagai, Roy Kadowaki, Sakari Suzuki, and Bunji Tagawa signed a document denouncing Japanese fascism. Taro Yashima departed Japan in 1939, enlisted in the U.S. Army, and served as an artist for the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Yashima published a 310-page autobiographical picture book, The New Sun, for adults about prewar Japan in 1943.

Statement of the Arts Council of Japanese Americans for Democracy, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Chairman, February 11, 1944. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Ayako Ishigaki was an Issei journalist, activist, and feminist who published a memoir, Restless Wave, in 1940, with the help of Kimi Gengo Tagawa. It was acclaimed in the U.S., though its strong criticism of wartime Japanese society and militarism also led to negative attention from the Japanese government. Ayako and her spouse, the artist Eitaro Ishigaki, had to register as enemy aliens but didn’t face imprisonment because of their pro-democracy sentiments. Nonetheless, they were subject to curfews, random searches, and job loss. In 1942, Ayako began working for the OWI.

From 1943 to 1944, Kimi Gengo Tagawa published a series of stories in The Bookshelf, a magazine for the Girl Reserves, a popular club program within the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) that began in 1918 to foster patriotic war work, and later became a way to incorporate minorities into the organization’s activities In these stories. In these stories, Kimi used fictional conversations to educate readers about American and Japanese culture, immigration, and assimilation. Kimi’s spouse Benji Tagawa was also active in JACD and contributed illustrations for Kimi’s book To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor.